Le Plongeon mastered the Maya language while in Yucatán and befriended local Maya priests, including one wisdom keeper he believed to be 150 years old. Adding a Casteneda-like mysticism to his life among the temples, he sometimes experienced dislocations of time and space while working at the site, or a bright light that inexplicably bathed them in a mystic glow. He felt that among the Maya survived “a rich living current of occult wisdom and practice, with its sources in an extremely ancient past, far beyond the purview of ordinary historical research.” 15We can imagine Maya archaeologist J. Eric S. Thompson thinking something along the same lines, considering his long-term friendship with Jacinto Cunil, his Maya compadre (his spiritual “co-godparent”), whom Thompson greatly respected.

But Le Plongeon, unfettered by university propriety, went far beyond anything Thompson would have dared commit to print, and speculated that the pre-Columbian Maya practiced mesmerism, were clairvoyant, and used magic mirrors to predict the future. They did have “magic mirrors” of a sort—dark obsidian reflecting dishes and pyrite plates—as well as oracular scrying stones, one of which fell into the hands of Elizabethan astrologer John Dee. Through this magical object from across the western ocean Dee communicated, by his own frank reports, with angels. 16

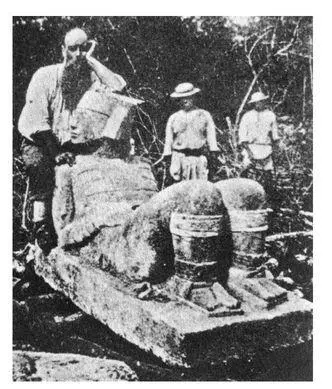

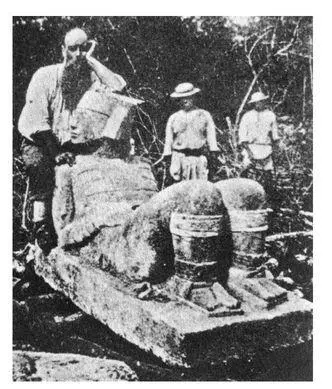

Le Plongeon’s most impressive achievement, the recovery of a massive stone Chac Mool sculpture from a depth of twenty-two feet under Chichén Itzá’s ground level, remains one of the truly bizarre events in Mesoamerican archaeology. For it must be said that, although his methods were odd and primitive by modern standards, Le Plongeon was in 1876 one of the first archaeologists digging in Mexico. His methods were, admittedly, unorthodox. On one of the buildings at Chichén Itzá, Le Plongeon claimed he had deciphered the glyph for “Chac Mool” and he could thereby pinpoint a place to dig where he would find an effigy of this deity. To all appearances the spot was located more by random selection than by a hieroglyphic map. His assistants labored for days, and everyone must have thought the endeavor was doomed, when at a depth of twenty-two feet they struck solid stone. As they dug around its contours a huge sculpture in-the-round took shape. Using only jungle vines, tree trunks, and bark, they managed to raise it to the surface. A picture survives of a bemused and tired-looking Le Plongeon sitting next to the monolith he dubbed Chac Mool, right outside the hole where it had been interred for centuries. His long Rasputin-like beard and wide forehead are somehow archetypal, a nineteenth-century Indiana Jones destined from birth to do what he just did.

His comments about the Maya culture being 12,000 years old are somewhat understandable given the depth at which this sculpture was found. In fact, its depth is hard to explain unless the Maya themselves buried it when they would have had to do so, a brief nine centuries earlier, which is currently the consensus opinion of archaeologists. After raising the monolith, Le Plongeon promptly wrote a letter to the president of the Republic of Mexico, advising him of his findings and intentions, while offering a lesson in the antiquity and genius of the Maya race:

The results of my investigations, although made in territories forbidden to the whites, and even the pacific Indians obedient to Mexican authority; surrounded by constant dangers, amid forests, where, besides the wild beasts, the fierce Indians of Chan-Santa-Cruz lay in ambush for me; suffering the pangs of hunger, in company with my young wife Alice Dixon Le Plongeon, have surpassed my most flattering hopes. Today I can assert, without boasting, that the discoveries of my wife and myself place us in advance of the travelers and archaeologists who have occupied themselves with American antiquities. 17

Le Plongeon raises the Chac Mool. From Salisbury (1877)

From somewhere that magic figure of 12,000 years was invoked:

The atmospheric action, the inclemencies of the weather, and more than that, the exuberant vegetation, aided by the impious and destructive hand of ignorant iconoclasts, have destroyed and destroy incessantly these opera magna of an enlightened and civilized generation that passed from the theatre of the world some twelve thousand years ago, if the stones, in their eloquent muteness, do not deceive. 18

Always ambitious, Le Plongeon hoped to display the monolith in time for the 1876 United States centennial celebration in Philadelphia. He and his crew succeeded in dragging the two-ton sculpture by oxcart sixty-five miles to Mérida, where it was promptly seized by the local authorities (they simply waited until it was delivered into their hands). They, in turn, were one-upped by a warship from the central government, which took it and then transported it to a rail line that brought it to Mexico City, where it resides today.

Although dejected at this loss, Le Plongeon renewed his effort to bring his findings before the community of intellectuals and scientists. He sent small artifacts and photographs to Philadelphia, which were conveyed to Stephen Salisbury, an active member of the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts, who agreed to publish some of Le Plongeon’s findings in the society’s journal. The relationship eventually bogged down as Le Plongeon’s radical views of human history were laid out in each subsequent article.

He spoke of ancient connections between the Western Hemisphere and Asia, Africa, and Europe. Based on his archaeological findings, he described previous cycles of humanity going back tens of thousands of years. Plato’s Atlantis and the ancient Egyptians were all part of the picture. It was too much for the proper New England intellectuals associated with the Antiquarian Society; Le Plongeon’s cosmic views offended their Christian sentiments. Civilization going back 12,000 years? Why, everyone knew that the earth was created in 4004 BC. Bishop Usher had demonstrated that—it’s in the Bible. Atlantean fantasy was trumped by biblical fantasy, and Le Plongeon’s writings were no longer welcome in that thinking man’s journal.

Salisbury washed his hands of Le Plongeon and, with Charles Bowditch of the Peabody Museum of Anthropology in Cambridge, found another Yucatán liaison in a young man named Edward Thompson. For many years Ed Thompson worked hard at Chichén Itzá, dredging the cenote for gold and other objects, and stayed in Yucatán for three decades. Having arrived in Yucatán in 1885, the year Le Plongeon left, Thompson’s more reasonable, levelheaded exploration and documentation could commence. His credentials? Thompson had aroused excitement in scholarly circles with an article he had published in Popular Science Monthly . The title of the article was “Atlantis Not a Myth.”

PHOTOGRAPHY LEADS TO DECIPHERMENT

Stephens and Catherwood are considered to have triggered the scientific investigation of Maya archaeology, but it was a process of fits and starts. Eventually, explorers were making efforts to carefully document the carvings and measure the sites. But for many decades these careful investigators continued to rub shoulders with the Atlantis hunters. Sometimes, they were one and the same person.

The distinction between professional investigator and independent explorer was less clear-cut than it is today. Writers who harbored Atlantean fantasies also contributed legitimate breakthroughs. And even into the twentieth century, when the methodologies of archaeological and anthropological science were perfected and applied with great care, many of the most significant breakthroughs continued to be made by independent, outside-the-field thinkers. It’s a situation that characterizes, and practically defines, the process of breakthroughs in Maya studies.

Читать дальше