Today, four levels are preserved in the four high school years, and beyond that three levels are preserved in the bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees. The master of knowledge is bested only by a doctor, who unlike the master can confer knowledge and degrees on others.

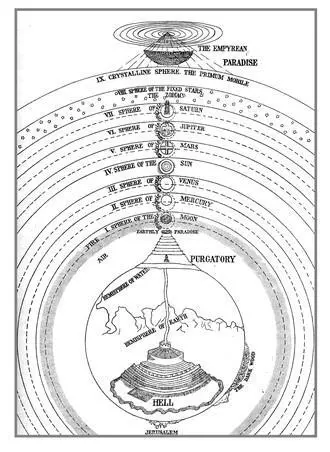

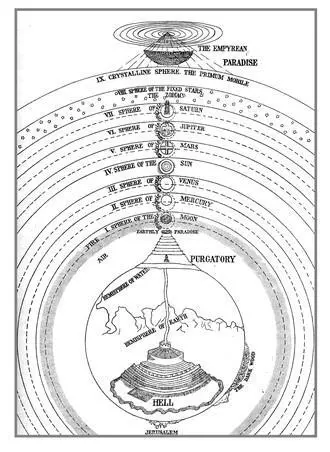

Dante’s multidimensional cosmos based on the Neoplatonic cosmology of seven planetary domains

Notice that the Trivium, in modern times, has been switched with the location of the Quadrivium, a circumstance that is revealing in that an inversion of perspective on what is real has occurred in modern times; spirit and spirituality is ambiguous, suspiciously subjective, and unreal, while matter (the physical) is the part of reality that everybody agrees exists.

With this broader framework placed on the shelf for moment, let’s slow down and simply consider the implications of the most accessible level, the tangible reconstruction of the Long Count calendar, the 2012 date, and Maya cosmology. If progress at this level can be even partially initiated, a revolution in Maya studies is in order, since at this stage professional scholars don’t regard 2012 as an intentional artifact of Maya thought and therefore it doesn’t have, for them, any merit as a valid topic of rational inquiry.

MAYA COSMOLOGY, MYTHOLOGY, AND CALENDRICS

The 13-Baktun cycle that ends on December 21, 2012, represents a large cycle of time. Dated carvings and hieroglyphic texts indicate that this cycle, lasting 5,125.36 years, was conceived as an Era or Age. It therefore belongs to a doctrine of World Ages in which each new Age begins with a Creation event. Scholars studying Maya iconography related to these Creation Myth narratives have identified deep connections between this calendar cycle, Maya mythology, kingship rites, and astronomy.

Recent breakthroughs in understanding the 2012 calendar are built upon previous breakthroughs. The discovery of carved monuments at archaeological sites in the 1800s, the decipherment of calendar glyphs, figuring out the correlation of the Long Count calendar with our own—all of these things had to happen before one could notice that a 13-Baktun cycle ends on the December solstice of 2012. I underscored how this fact was theoretically available to scholars as early as 1905, then 1927, more likely by 1946, and was finally noted in print (if one applied an important corrective caveat) with Michael Coe’s 1966 book The Maya .

The precise solstice placement of the cycle ending in 2012 was challenged by linguist Floyd Lounsbury, who in 1983 argued for a reinstatement of the original GMT correlation of 1927, which makes the end date fall on December 23, 2012—two days after the solstice. Lounsbury’s argument, published in two papers, has not stood up to a centrally important issue—the survival of the 260-day count in highland Guatemala. 5Lounsbury made some highly regarded breakthroughs in epigraphy and was deeply involved in the exciting hubbub that surrounded the Palenque conferences in the 1970s.

Thompson, the old gatekeeper, died in 1975 and the floodgates were opened for a more interdisciplinary approach to deciphering the script. And progress happened quickly. But there was also a backlash against Thompson and the vindictive darts, long repressed, were thrown. It’s quite possible that Lounsbury’s attack on Thompson’s revised 1950 correlation, which makes the end date fall precisely on December 21, 2012, was motivated by a desire to knock him down a few pegs, posthumously, as Thompson himself had done to linguist Benjamin Whorf.

At the Palenque conferences in the 1970s, Lounsbury was Linda Schele’s epigraphic mentor. She dedicated her 1990 book Forest of Kings to him. Not being completely immersed in the correlation debates, Schele adopted and propagated Lounsbury’s December 23 date, and Michael Coe followed suit in his fascinating 1992 book Breaking the Maya Code . Consensus prevailed, and for all appearances scholars agreed that the cycle ending fell not exactly on the solstice but on December 23. But despite this uncritical support from Schele and Coe, Lounsbury had to confront several better-informed detractors.

There are two points of Lounsbury’s work that are central to his thesis and reveal the flaws. His argument is based on the Venus almanac in the Dresden Codex, which provides predictive dates for the first appearance of Venus as morning star. These occur on average every 583.92 days. Lounsbury tested the two correlations and found that the December 23 correlation was more accurate for a selected portion of the predictive almanac. However, Maya scholar Dennis Tedlock and Maya scholar-astronomer John B. Carlson pointed out that the morning star risings of Venus vary between 580 and 588 days—sometimes even from cycle to cycle. 6Lounsbury had worked from the theoretical average of the cycle, rather than how the cycle actually happens in the sky. His two-day variance was not supported by the inherent vagaries of the Venus cycle itself.

The second problem with Lounsbury’s theory is even more definitive. The ancient Creation monuments contain both Long Count and tzolkin dates combined. We can thus read on Quiriguá Stela C that the last 13-Baktun cycle ended on 13.0.0.0.0 in the Long Count, coordinated with 4 Ahau in the 260-day tzolkin. The current 13-Baktun cycle will of necessity also occur on the same coordination of dates, because 260 divides evenly into the full 13-Baktun cycle. The Long Count dating method was lost centuries ago, as previously explained, but the 260-day calendar has survived in Guatemala. Ethnographers such as Barbara Tedlock have shown that this surviving day-count represents an unbroken tradition going back to the Classic Period Maya, and beyond to the very dawn of the calendars. She wrote in her important book Time and the Highland Maya :

Among the Lowland Maya of Yucatan, the ancient ways of reckoning and interpreting time are known from inscriptions on thousands of stone monuments, from the few ancient books that survived the fires of Spanish missionaries, and from early colonial documents. But the contemporary indigenous people of that region have long since forgotten how to keep time in the manner of their ancestors. With the Highland Maya, and especially those of the western highlands of Guatemala, the situation is reversed. Here, the archaeological monuments are bare of inscriptions, and not one of the ancient books escaped the flames, though the content of a few such books was transcribed into alphabetic writing and preserved in colonial documents. But it is among the Highland Maya rather than among their Lowland cousins that time continues to this day to be calculated and given meaning according to ancient methods. Scores of indigenous communities, principally those speaking the Maya languages known as Ixil, Mam, Pokomchi, and Quiché, keep the 260-day cycle and (in many cases) the ancient solar cycle as well. 7

The 20 day-signs and the 13 numbers have been tracked sequentially without break. The surviving day-count thus provides a test for any proposed correlation because it locates the authentic placement of the tzolkin and, therefore, the Long Count. If we ask a Quiché Maya day-keeper what day it is today, January 9, 2009, they will respond it is “5 Tijax.” Then, if we start with this day-count placement and count forward … January 9 = 5 Tijax, January 10 = 6 Kawuq, January 11 = 7 Junajpu … to December of 2012, we find that 4 Junajpu (4 Ahau) falls on December 21, not December 23. In this way, the surviving unbroken day-count confirms the revised GMT correlation of 1950. Lounsbury understood this issue, which was brought to his attention by Dennis Tedlock and other scholars, and tried to salvage his theory by proposing that a two-day shift in the day-count must have occurred prior to the Conquest. It had to happen before the Conquest because we have three historical date correlations from the Conquest period, from three widely separated regions—Central Mexico, Yucatán, and Guatemala. They all confirm the December 21, 2012, correlation. 8

Читать дальше