There are four Year Bearers because the five-day “extra” month in the haab makes each successive New Year’s Day toggle forward five days in the tzolkin. Since there are twenty day-signs, it takes four of these five-day leaps to return to the first Year Bearer; thus, four Year Bearers. The Year Bearers symbolize the four directions, the four quarters of the year (two equinoxes and two solstices), and the four sacred mountains. Of the four Year Bearers one is chief, and in the earliest calendar system the chief Year Bearer was symbolically associated with the December solstice, because that is the most important turnabout day in the year, when the light returns and the sun is reborn. For the modern Quiché Maya the chief Year Bearer is Kej (Deer). A Calendar Round (roughly 52 years) is completed when the chief Year Bearer cycles through the 13 numbers until it once again has a 1 coefficient. The next Quiché Calendar Round begins on 1 Deer, February 18, 2026. This means that the present Calendar Round began on 1 Deer on March 3, 1974.

The cycles of Venus were brought into this calendar scheme by a fortunate relationship with the double Calendar Round. Venus goes through periods as evening star and morning star, and will rise in the east as morning star every 584 days. The Mesoamerican astronomers noticed that five of these Venus periods equal eight years. In other words, Venus will rise as morning star five times every eight years, returning to the same place in the zodiac. In effect, Venus traces a five-pointed star around the zodiac during this time, explaining the ancient Babylonian association of Venus with pentagrams. All of the cycles of sun, tzolkin, and Venus are completed in two Calendar Rounds, just under 104 years. This period is called the Venus Round.

The 52-haab Calendar Round is a complete system of timekeeping and was used throughout Mesoamerica in ancient times. In fact, the Aztecs used it in their New Fire ceremony, in which the Pleiades were observed passing through the zenith at midnight at the end of a Calendar Round period. In my 1998 book Maya Cosmogenesis 2012 I reconstructed how this tradition was designed to track the celestial shifting called the precession of the equinoxes. The New Fire ceremony and Calendar Round periods were essential to the Central Mexican understanding of World Ages.

The Maya used this system but also developed their own unique timekeeping system, the Long Count. This is the calendar that targets 2012 as the end of a vast cycle of time, a key concept in the Maya doctrine of World Ages. The Long Count basically utilizes five place values. It is often said that it is a base-20 system, which is generally true, but in fact two of the five levels do not follow the base-20 math:

1 day = 1 Kin (day)

20 days = 1 Uinal (vague month)

360 days = 1 Tun (vague year)

7,200 days = 1 Katun (19.7 years)

144,000 days = 1 Baktun (394.26 years)

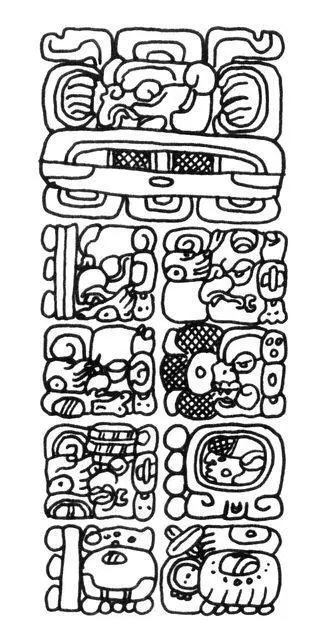

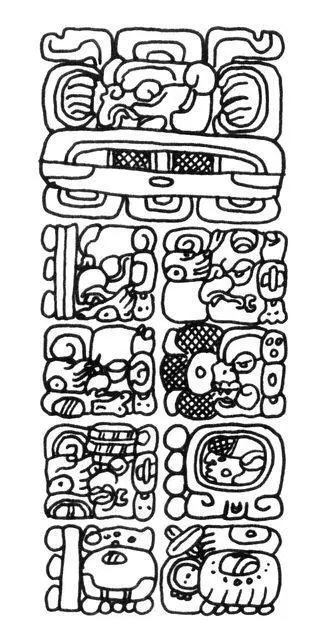

13.0.0.0.0 Creation Text from Quiriguá, August 11, 3114 BC. Drawing by the author

Thirteen Baktuns equal 1,872,000 days, which is one “era” or World Age cycle (5,125.36 years). Notice that the Baktun is multiplied by 13 rather than 20 to reach to World Age cycle, and the Uinal is multiplied by 18 rather than 20 to reach the Tun. We know that the 13-Baktun period ends on December 21, 2012, because, as we saw in Chapter 1, scholars have verified Goodman’s work that accurately correlated our Gregorian calendar with the Maya Long Count.

A date in the Long Count utilizes “dot and bar” notation, in which a dot equals one and a bar equals five. A typical date on a carved monument is pictured to the left.

You can see two bars and three dots in the upper left, next to a Baktun glyph. There are no dots or bars in the following glyphs for Katun, Tun, Uinal, and Kin, because those values are zero in this example. Next follows the tzolkin date, 4 Ahau (four dots next to the Ahau day-sign). And finally, in the lower left, 8 Cumku in the haab calendar. The final glyph block contains the event: “the image was made to appear.” 15

Scholars have simplified the notation so that a Long Count date written 9.16.4.4.1 means that 9 Baktuns, 16 Katuns, 4 Tuns, 4 Uinals, and 1 day have elapsed since the zero day of the Long Count, which the correct correlation fixes at August 11, 3114 BC. The “zero” date is written 0.0.0.0.0 but can also be written 13.0.0.0.0 (as the completion day of the previous cycle). The “end-date” of a 13-Baktun cycle is thus written 13.0.0.0.0. The use of the term “end-date” gives rise to the mistaken notion that the Maya calendar ends in 2012. But Maya time is cyclic, and it should go without saying that time continues into the next cycle. We use similar conventions in our language when we speak of “the end of the day,” but we don’t expect the world to end at midnight.

After decades of testing, the correlation question was finally settled by 1950. The result was that the 13th Baktun would end on December 21, 2012, on the tzolkin day 4 Ahau. This date in the tzolkin confirmed the surviving day-count in highland Guatemala, and also validated the carvings in the archaeological record called Creation monuments, which always correlate 13.0.0.0.0 with 4 Ahau.

The correlation issue is settled, and in my experience confusion arises only among those who have not studied or understood the topic. Thus, many popular books dismiss or neglect the correct correlation and instead proceed to invent new correlations, including completely fabricated day-counts as well as alternate end-dates. A great deal of unity could be achieved if researchers and writers would understand and heed the fundamentals of the Maya calendar. A primary fact that needs to be appreciated is what I call “the equation of Maya time,” which is this: 13.0.0.0.0 = December 21, 2012 = 4 Ahau. 16

In addition to these systems, the Maya also tracked the 9-day cycle of the Lords of the Night, as well as an 819-day cycle that involves Jupiter. Even a basic introduction to the Maya calendar can get quite complex. For the purpose of understanding 2012, one first needs to know that December 21, 2012, is the end of the 13-Baktun cycle in the Long Count calendar, and in Maya philosophy the 13-Baktun cycle equals one “World Age.” Furthermore, it is important to clarify that December 21, 2012, is not the invention of imaginative modern writers but is a true and established artifact of the Maya philosophy of time.

THE CLASSIC PERIOD: THE LONG COUNT IN ITS PRIME

The way in which the Long Count appears in hieroglyphic texts reveals its multifarious uses. It provided a sequential day-count from the zero date baseline. It provided interval calculations between two dates, sometimes tens of thousands of years apart. It was a framework for astronomical calculations. Solstice and equinox dates fall within the framework of the Long Count in a predictable pattern, suggesting that it incorporated an accurate tropical year calculation, which modern science places at 365.2422 days. 17Three Katuns in the Long Count equal 37 Venus cycles of 584 days. Thus, if a Venus event, such as a first appearance as morning star, happened on 9.11.0.0.0 in the Long Count, Maya astronomers were on the alert for the same event three Katuns later, on 9.14.0.0.0.

Let’s look at an early Classic Period inscription, from Tikal Stela 31. In this case it’s a retrospective date, made by a ruler named Stormy Sky (Siyaj Chan K’awil II) recalling his grandfather’s accession to kingship on 8.18.15.11.0 (November 25, 411 AD). Maya scholars Linda Schele and David Freidel noted that Jupiter and Saturn were in conjunction on this date, precisely when Venus had reached its evening star “station” (stationary between forward and retrograde motions). 18Maya scholar Michael Grofe pointed out to me that the date was also within a few days of a visible solar eclipse. 19The Maya would have expected this Venus station to happen again three Katuns later, on 9.1.15.11.0. Apparently, Stormy Sky’s grandfather selected the date of his coronation to correspond to these celestial events, as it would confer upon him a special relationship with the sky deities.

Читать дальше