Robert Service

SPIES AND COMMISSARS

Bolshevik Russia and the West

To Adele, with love and thanks

Many people have given generous help with this book. Its basic material on all aspects of Russia and the West in the revolutionary period comes from the Hoover Institution Archives, and I am grateful for the support of the Sarah Scaife Foundation in enabling me to work in Stanford on the project over two whole summers. My thanks also go to Hoover Institution Director John Raisian and Senior Associate Director Richard Sousa for the enthusiasm they have shown for the investigations carried out at Hoover. The exceptional conditions for research and writing there were enhanced by the active co-operation of all the staff in the Archives, and I am especially beholden to Linda Bernard, Carol Leadenham, Lora Soroka, Zbig Stanczyk, Brad Bauer and Lisa Miller. Their efficiency and expertise in suggesting boxes and folders unknown to me and in helping with the declassification of valuable files are appreciated. In that respect I must acknowledge my debt to Julian Evans, UK Consul-General in San Francisco until 2010, who persuaded the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office to sanction access to some of Robert Bruce Lockhart’s papers at Hoover.

Scholars in the San Francisco Bay area gave me ideas and discussed aspects of the research: Robert Conquest, David Holloway, Norman Naimark, Yuri Slezkine and Amir Weiner. It was a pleasure to try out some of the ideas for the book with them in convivial circumstances.

In Britain, Roy Giles shared his expertise on intelligence matters and Simon Sebag Montefiore helped to steady my instincts about the book’s argument and orientation. My literary agent David Godwin has been unfailingly supportive about this project. As usual it was a joy to talk over ideas with him. My thanks go, too, to Norman Davies and Ian Thatcher for answering specific questions. Andrew Cook kindly shared several products of his sleuthing in the UK archives about British intelligence in 1918; Harry Shukman did the same with his copies of British official papers on Georgi Chicherin. I am grateful to both Andrew and Harry as well as to Michael Smith for answering questions on various research topics — and to Angelina Gibson for assistance with the Bulgarian language. Thanks are due to John Murphy of the British Broadcasting Corporation, who alerted me to material in Oxford on Allied politics and intelligence while we worked together on a radio programme about the British plot of 1918. Richard Ramage, Administrator and Librarian of the Centre of Russian and Eurasian Studies, was patient and helpful with my frequent enquiries about our library holdings at St Antony’s College.

Harry Shukman cheerfully agreed to examine the entire first draft, and his expertise in Moscow and London history are much appreciated. Likewise Katya Andreyev, at short notice, went through the chapters; I had talked with her about several themes and am grateful for her agreeing to look over what I did with the advice. Roland Quinault generously read the draft while on his travels in the US and gave advice on British political history. Georgina Morley, my editor at Macmillan, went through the draft with imaginative care and prompted many amendments of style and content; and I have yet again been very fortunate in working with Peter James as copy-editor. My wife Adele Biagi, above all, looked at the draft not once but twice. Like me, she caught the contagion of interest in British politics and intelligence in the early Soviet period. Her deft, insightful touch with the chapters saved me from innumerable misjudgements and infelicities.

Some last technical points. I have been flexible about transliteration, using a simplified variant of the US Library of Congress scheme. But the conventional renderings of Trotsky, Zinoviev, Benckendorf and others are retained. So too are the ‘Anglo-Russian’ variants of certain Polish and Latvian names such as Felix Dzerzhinsky and Yakov Peters whenever the individuals were notably Russified in their culture. The names of certain institutions, too, are simplified. For example, the People’s Commissariat for Army and Navy Affairs appears as the People’s Commissariat for Military Affairs. The book uniformly uses the Gregorian calendar even though the Russians in Russia officially used the older Julian one until January 1918. I recognize that this makes for one big oddity inasmuch as the Bolshevik seizure of power in November 1917 is universally known as the October Revolution, but it would surely be perverse after all these years to start calling it the November Revolution. For purposes of concision, the US is referred to as one of the Allies even though it formally called itself an Associated Power.

Robert Service March 2011

The story of the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917 has been told a thousand times and usually the focus is on Russian events to the exclusion of the global situation. There is nothing wrong with examining ‘October’ and its consequences in such a fashion. But this book is an attempt to see things in a different light. The early years of Bolshevik rule were marked by dynamic interaction between Russia and the West. These were years of civil war in Russia, years when the West strove to understand the new communist regime while also seeking to undermine it; and all through that period the Bolsheviks tried to spread their revolution across Europe without ceasing to pursue trade agreements that might revive their collapsing economy. Looking at this interaction in detail reveals that revolutionary Russia — and its dealings with the world outside — was shaped not only by Lenin and Trotsky, but by an extraordinary miscellany of people: spies and commissars certainly, but also diplomats, reporters and unofficial intermediaries, as well as intellectuals, opportunistic businessmen and casual travellers. This is their story as much as it is the story of ‘October’.

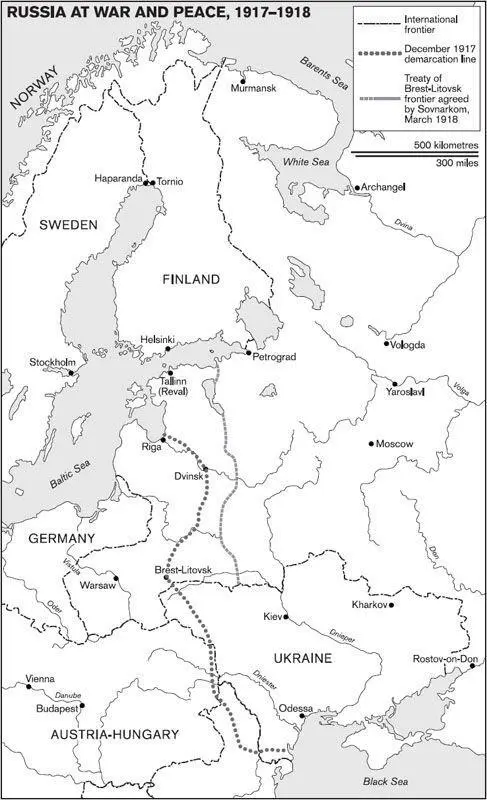

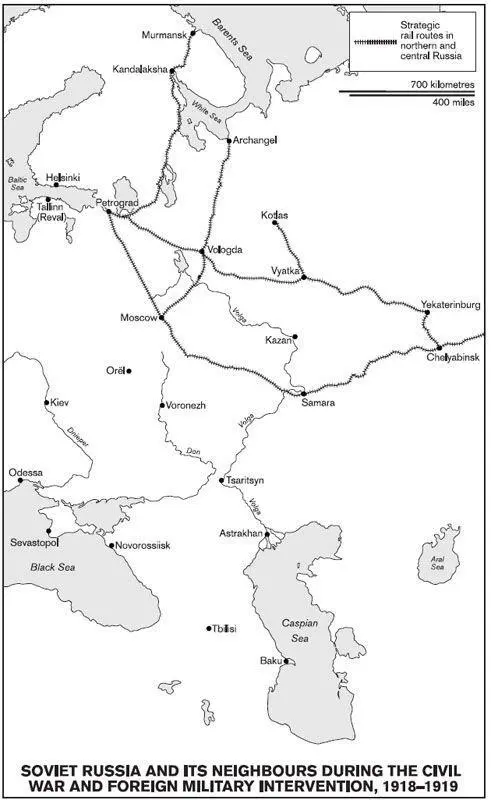

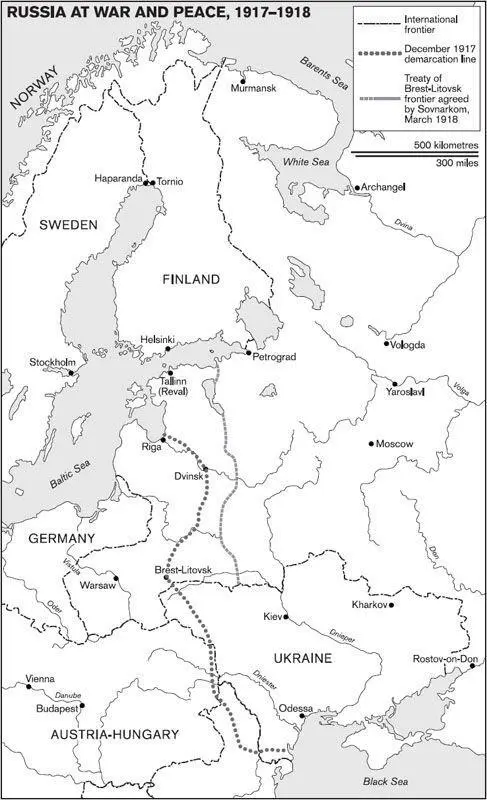

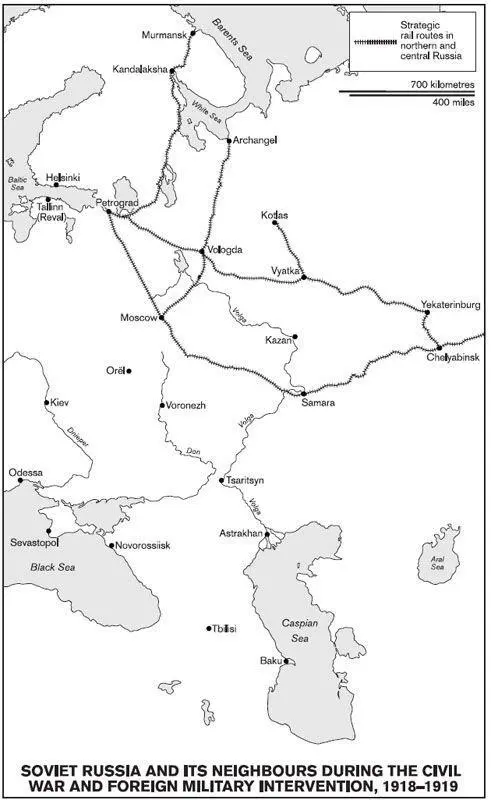

The communist leaders believed that their revolution would expire if it stayed trapped in one country alone; they were gambling on their hope that countries elsewhere in Europe would soon follow the path they had marked out in Russia. The October Revolution happened in Petrograd — as the Russian capital St Petersburg had been renamed to do away with its Germanic resonance — while the Great War between the Allies and the Central Powers raged across Europe, and until November 1918 the world’s powers gave little thought to revolutionary Russia except when examining how its situation could be exploited to their advantage. The Germans had signed a separate peace with Lenin’s government at Brest-Litovsk in March that year in order to redeploy their army divisions in the east to serve on the western front against France, Britain and the US; the French and British meanwhile increased their efforts to bring Russia back into the fight against Germany even if this meant bringing down the communist government. When peace came to Europe after the German surrender, the ‘Russian question’ was transformed in content as Western politicians at last gave priority to preventing the contagion of communism from spreading beyond the Russian borders into the heart of Europe. Sporadic revolutionary outbreaks in Germany, Hungary and Italy occurred but, to the frustration of the Russian communist leadership, petered out in failure. The Western Allies meanwhile undertook direct military intervention in Russia as well as the subsidizing of the anti-communist Russian armed forces. But in late 1919, when these enterprises ran into difficulty, they withdrew their expeditionary forces. Communist Russia had survived its first international trial of strength.

Читать дальше