The 1st and 9th Armies tried to cross the Roer River and the Hürtgen Forest a few miles to the east of Aachen. Six American divisions were chewed up (35,000 men lost) in bitter close-in attrition battles in and around those dark woodlands in three months beginning September 12.

Meanwhile Jake Devers’s 6th Army Group (U.S. 7th and French 1st Armies) reached Strasbourg and the Rhine on the east by December 15. But across the Rhine lay the Black Forest, no acceptable route to the heart of German power.

The key to Hitler’s plan was to strike at a time when bad weather would endure for a week, keeping Allied aircraft out of the sky for that period. He figured it would take his panzers that long to reach Antwerp.

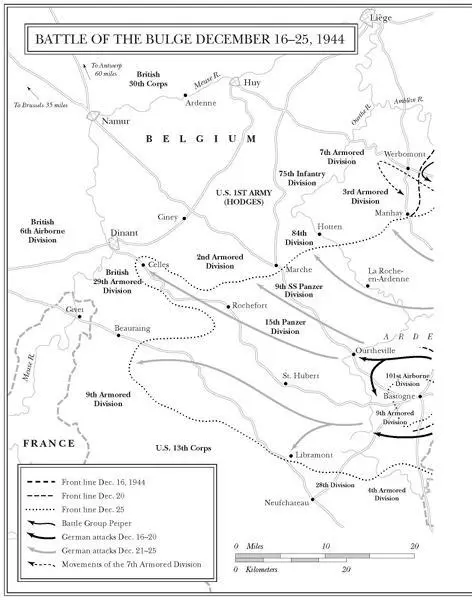

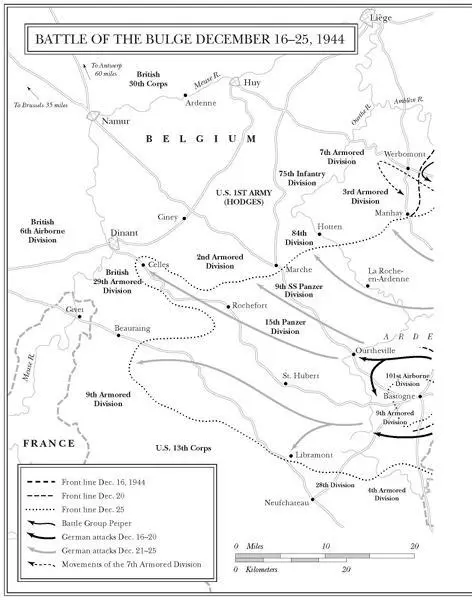

The major obstacle was the Meuse River, just beyond the Ardennes. The first wave of tanks had to seize bridgeheads over it quickly. Then a second wave of panzers was to strike off for Antwerp, while infantry divisions fanned off north and south to protect the flanks of the salient.

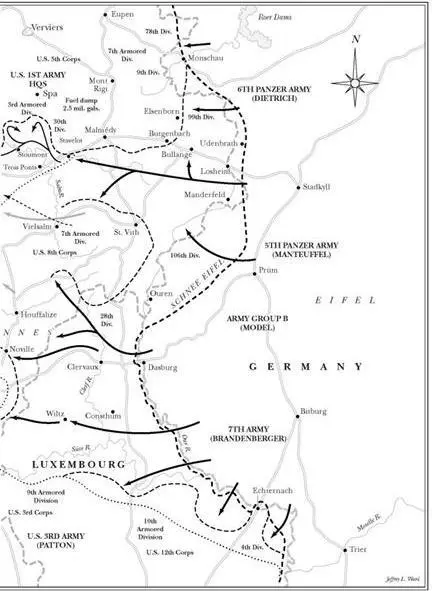

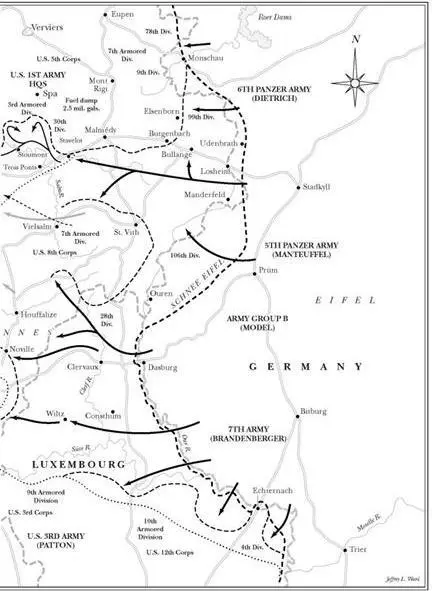

The final plan was for the offensive (code-named Herbstnebel, or Autumn Mist) to be launched by twenty divisions, seven of them panzers, along a sixty-mile front from Monschau, twenty miles southeast of Aachen, to Echternach. Sepp Dietrich’s 6th Panzer Army was to deliver the main effort—or Schwerpunkt— from Monschau to Losheim, fifteen miles south, exactly the place Erwin Rommel’s 7th Panzer Division had driven through in the 1940 campaign. Dietrich was to cross the Meuse south of Liège, then head for Antwerp, while anchoring his northern flank on the east-west Albert Canal.

On Dietrich’s left or south, Hasso von Manteuffel’s 5th Panzer Army was to attack through and south of St. Vith, cross the Meuse at Namur, then wheel northwest, bypassing Brussels, and guard Dietrich’s flank.

South of Manteuffel, Erich Brandenberger’s 7th Army, primarily infantry, was to attack on either side of Echternach, move west, and peel off divisions to block movement from the south.

A plan for a converging attack by 15th Army around Aachen had to be dropped, since troops had to be sent east to meet Soviet pressure. Consequently, Hitler could not block the Allies from bringing down reserves from the north.

Nevertheless, if all went well, more than a million Allied troops would be surrounded. But how such a huge army was to be defeated, even if encircled, no one really knew.

Secrecy was mandatory. Hitler prohibited transmission by telephone, telegraph, or radio. The few let in on the plan signed a pledge of secrecy on the pain of death. Rundstedt was not brought into the picture until the late stages.

On October 21, Hitler called in Otto Skorzeny, the officer who had rescued Benito Mussolini from his captors in 1943. Hitler promoted him to SS lieutenant colonel and told him to form a special force to go in advance of the offensive. In the first wave, a company of English-speaking commandos, wearing American field jackets over their German uniforms and riding in American jeeps, was to rush ahead, cut telephone lines, turn signposts to misdirect reserves, and hang red ribbons to imply roads were mined. Second, a panzer brigade of 2,000 men in American dress was to drive through and seize the bridges over the Meuse.

The second wave never materialized. Army command failed to provide the American equipment needed. But the first wave had astonishing success. Forty jeeps got through, and all but eight returned. The few Germans who were captured created the impression that many sabotage bands were roving behind the front. MPs and other soldiers stopped every vehicle, questioning drivers to see if they were German. Traffic tie-ups created chaos, and hundreds of innocent Americans were arrested.

General Bradley himself had to prove his identity three times: “The first time by identifying Springfield as the capital of Illinois (my questioner held out for Chicago); the second time by locating the guard between the center and tackle on a line of scrimmage; the third time by naming the then current spouse of a blonde named Betty Grable. Grable stopped me but the sentry did not. Pleased at having stumped me, he nevertheless passed me on.”

Rundstedt was appalled when he learned of the offensive. “Available forces were far too small for such an extremely ambitious plan,” he said. “No soldier believed that the aim of reaching Antwerp was really practicable.”

If the Germans crossed the Meuse, both flanks would be vulnerable to a major counterstrike. All that would happen, Rundstedt predicted, would be a deep salient or bulge into the line, costly and indecisive. Field Marshal Walther Model, commander of Army Group B, shared Rundstedt’s pessimism, but neither could get Hitler to change his plans.

To direct the offensive personally, Hitler moved his headquarters from East Prussia to his Adlerhorst— Eagle’s Aerie—in the Taunus hills east of the Rhine near Bad Nauheim.

Hitler designated twenty-eight divisions for the offensive, twenty in the first wave with 250,000 men, a remarkable figure given Germany’s defeats. The new soldiers were green, of course, without the thorough training of the splendid troops who had swept through the Ardennes in 1940. But there was a hard core of combat veterans and tough noncommissioned officers to stiffen the recruits, plus a number of officers seasoned in battle. The most serious problem was motor transport. No division had more than 80 percent of the vehicles it needed. Fuel was in short supply, and most stockpiles were east of the Rhine.

Even so, Hitler had assembled a thousand tanks for the opening wave in seven panzer divisions, and 450 for the follow-up force. Tactical aircraft were the weakest element: Hermann Göring found only 900, half the number the Luftwaffe deployed in 1940, and a fifth the number of bombers the Allies could throw into the battle. Göring delivered this quantity only on one day—after the ground battle had been decided.

There were many signs of a German buildup opposite the Ardennes in the German Schnee Eifel Mountains, duly reported by air reconnaissance and by Ultra intercepts. But American intelligence (G-2) officers at all levels failed to draw the correct conclusion. They detected German armor but thought it would be used to counterattack the Allied drive toward the Rhine and Ruhr. G-2 saw troop movements in the Eifels as efforts to meet American offensives north and south of the Ardennes. Finally, they believed fuel was so short and troop losses were so great that the German army was in no condition to mount an offensive.

When the attack opened, Bradley was utterly confounded. “Just where in hell has this sonuvabitch gotten all his strength?” he asked his chief of staff, Leven Allen, at 12th Army Group’s tactical headquarters at Luxembourg City. And Eisenhower, who wrote that “I was immediately convinced that this was no local attack,” nevertheless waited till the evening of the second day to alert the two divisions he held in reserve, the 82nd and 101st Airborne. Only then did they start moving to the scene.

Hitler set the attack date for December 16, 1944. Bad weather was predicted for days ahead, keeping Allied aircraft from flying. Snow covered the ground. Hitler originally ordered a three-hour preliminary bombardment, but Manteuffel argued that a short, concentrated preparation would achieve the same effect while lessening the Americans’ alert. And rather than attack at 10 A.M., which Hitler planned, leaving fewer than seven hours of daylight, Manteuffel wanted the artillery concentrations to begin at 5:30 A.M., well before dawn. Half an hour later the ground assault would start, assisted by “artificial moonlight” created by bouncing searchlight beams off the clouds. Hitler accepted all the changes.

On the American side, the 5th Corps’s 99th Infantry Division, a new but reliable force, covered the region from Monshau south to Losheim. There the 14th Cavalry Group, equipped mainly with light weapons, protected the “Losheim Gap” itself—one of the few fairly open regions of the Ardennes, and thus the main avenue of approach.

Читать дальше

![Джонатан Димблби - Barbarossa - How Hitler Lost the War [calibre]](/books/385421/dzhonatan-dimblbi-barbarossa-how-hitler-lost-the-w-thumb.webp)