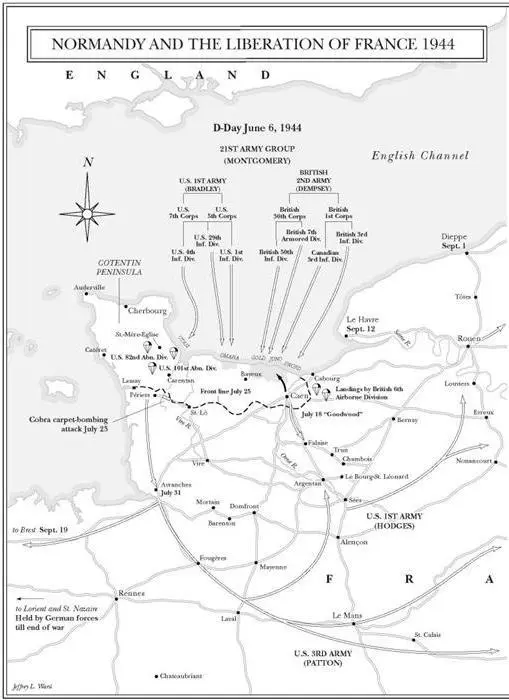

The result was chaos. Three-quarters of the paratroopers dropped so wide of their targets they never took any part in the attacks. Scattered through the countryside, they formed small groups, wandering for days, skirmishing occasionally with German patrols. Oddly the confusion helped. The Germans could not figure out Allied intentions and launched no strong attacks on the scattered men.

Major General Maxwell Taylor, commander of the 101st, could assemble only 1,000 men by the night of June 6, but was able to secure the exits to the causeways. The 82nd Division was unable to seize bridges to the west because much of the land was under water. However, the main objective was the village of St.-Mère-Eglise, five miles west of Utah beach, on a road leading northward into the Cotentin and southward to the town of Carentan and connection with Omaha beach.

Thirty men fell into the village itself, twenty of them right on the central square into the midst of the German garrison of a hundred men. Within a few minutes all the paratroops had been killed or captured. Private John Steele’s parachute caught on the church steeple, where he dangled for hours, playing dead, before finally being taken prisoner.

Other 82nd Airborne men assembled outside the village, and drove the Germans out by dawn.

In the British sector, Montgomery held up the landing for an hour and a half after the Americans landed in order to bombard the landing sites for two hours, four times as long as at Omaha. Large numbers of American B-17s and B-24s dropped their bomb loads on the targets, protected by some of the nearly 5,000 fighters the Allies had committed to the D-Day landings.

The land behind the flat beaches was low, and offered no great challenges to the British. The sector was defended largely by the 716th Division, containing many Poles and Ukrainians, and it put up a lackluster defense. The only threat from the air was from two FW-190 fighters based at Lille that made a single bold sweep along the beaches, guns blazing, before banking away and returning to base. On a cliff west of Le Hamel on Gold beach on the west a unit of the 352nd Division mounted an 88-millimeter antiaircraft gun with a clear field of fire. A round struck a landing ship, wrecking its engine room and turning it broadside up on the beach. Eventually a tank carrying a heavy mortar lobbed a forty-pound “flying dustbin” into the 88’s position and destroyed it. The British 50th Division, which landed at Gold, pushed four miles inland, but failed to capture the D-Day objective, Bayeux.

All across the British sector tanks fitted with flails moved up from the beaches, blowing up mines in their path. The tanks created lanes through which the infantry and vehicles could advance.

On Juno, the Canadian beach in the center, the Germans were waiting. Mines and shells sank many of the 306 landing craft. At Bernières, the 8th Canadian Brigade arrived ahead of its flail tanks. The assault regiment, the Queen’s Own Rifles, lost half of one company killed in the 100 yards it had to traverse from sea to sea wall. The Canadians broke through by point-blank fire from a gunship and a quick assault through one point of the defenses, and the Germans withdrew. The Canadians penetrated about four miles inland.

At Sword, on the east, the British 3rd Division lost 28 of 40 tanks in pitching seas, but the remaining 12 knocked out German gun positions. The division overran the enemy, pushed four miles inland, and linked up with the 6th Parachute Division along the Orne River, but failed to take the D-Day objective, Caen.

General Miles Dempsey, commander of 2nd Army, landed 75,000 men on D-Day at all three beaches, plus 8,000 paratroopers, and suffered about 3,000 casualties, one-third of them Canadian.

Meanwhile, nearly forty miles to the west, the U.S. 4th Infantry Division landed on Utah beach. The advance bombing by the air force had achieved little because a heavy overcast obscured the target, and most of the bombs landed far to the rear. An hour-long naval bombardment, however, was highly effective.

Utah was defended by one regiment of the 709th Division, another nonmobile outfit made up of older men and volunteers from the Soviet Georgian republic. The defenders raked the landing craft that came within their field of fire, but quickly surrendered.

By the end of the day, 23,000 Americans had landed on Utah, and the division had pushed six miles inland. Total casualties were only 197.

Omaha was utterly different. In the words of Omar Bradley, it was a nightmare. Before daylight, the invasion fleet, fearing shore batteries, anchored twelve miles off the coast. One of these batteries, at Pointe du Hoc, four miles west of the beaches, was reported to have six 155-millimeter guns with a range of 25,000 yards. Bradley had assigned two Ranger battalions to scale the high cliffs and destroy the guns.

Waves three to six feet high slapped the ships. Launching landing craft in darkness was difficult and dangerous. The “secret weapon” upon which the Americans were relying was the DD (for dual-drive) Sherman tank, equipped with canvas flotation gear and a boat screw. DDs were to be launched at sea and “swim” ashore to provide the troops instant artillery fire. Twenty-nine of the thirty-two DDs for the east sector were launched two and a half miles off the coast. All but two foundered, taking nearly all the crews to the bottom of the sea with them. Three others were landed directly on the beach. The seamen in charge of landing the thirty-two DDs on the western sector, horrified at what was happening, called off the sea launch and landed twenty-eight DDs directly on the beach, though only later—just two of the DDs intended to support the infantry made it ashore with the troops. Most of the amphibious DUKWs transporting 105-millimeter howitzers also foundered.

At 5:50 A.M. terrific salvos burst from the warships onto Omaha. The bombardment went on for thirty-five minutes. Meanwhile, beginning at 6 A.M., waves of B-24s dropped nearly 1,300 tons of bombs. The naval bombardment was partially effective, but the aerial bombardment was useless, falling well inland and missing the beach entirely.

The Omaha beach fortifications were formidable: three rows of underwater steel or concrete obstacles, most mined. The beach was two hundred yards wide with no cover. Beyond a low seawall were sand dunes and bluffs, cut by five draws the Americans intended to use as exits. All the draws were covered by German gun emplacements and the area between the seawall and cliffs was sown with mines.

At 6:30 A.M. the first waves of infantry, 1,500 men in 36 landing craft, hit Omaha: members of the 116th Regiment of the 29th Division and the 16th Regiment of the 1st Division, plus engineers to blow up underwater obstacles.

The Germans held their fire until the first wave of infantry hit the beaches. The initial burst of machine-gun fire came from a strongpoint only a quarter of a mile away from the lead craft. Others followed, creating a hurricane of fire. First out were men of the 116th on the west. As the ramps went down, they saw the shallows ahead whipped white by bullets. Men dropped dead or wounded as they lumbered forward in waist-deep water, creating a bloody surf that horrified everyone from the first moments. Other soldiers, seeing what was happening, tried to dive into deeper water and swim clear of the boats. But their heavy equipment dragged them down. Some drowned, others fought back to the surface. The survivors who dragged themselves ashore found no shelter, and some crawled back into the water for its scant protection. Within ten minutes every officer and sergeant had been killed or wounded. In Company A of the 116th, 22 men from one town—Bedford, Virginia—died, among them three sets of brothers.

Читать дальше

![Джонатан Димблби - Barbarossa - How Hitler Lost the War [calibre]](/books/385421/dzhonatan-dimblbi-barbarossa-how-hitler-lost-the-w-thumb.webp)