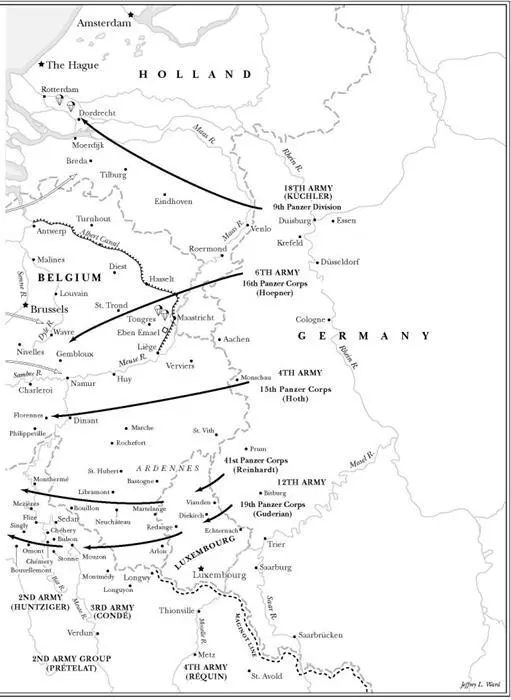

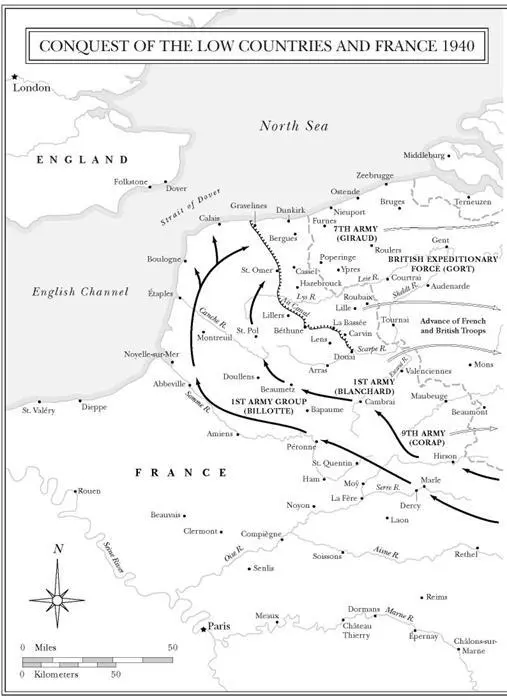

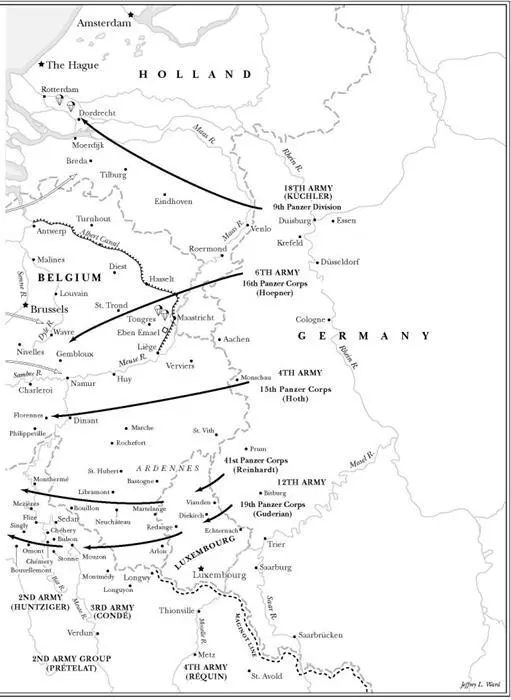

Behind the fast troops on the German right or northern flank were twenty-five infantry divisions. Stacked up behind Army Group A in the middle were thirty-eight infantry divisions. Their job was to fill out the corridor that the “panzer wedge” was to open. In the south along the Maginot Line were eighteen infantry divisions in Army Group C under Wilhelm von Leeb, with only a holding job.

The Allies had 3,370,000 men in 143 divisions—nine of them British, twenty-two Belgian, eight Dutch, the remainder French. The Germans committed 3 million men in 141 divisions. The Allies had almost 14,000 cannons, the Germans just over 7,000. However, the Allied guns were principally field artillery pieces designed to assist infantry. The Allies possessed too few guns required for the war about to be fought: antiaircraft and antitank weapons.

The Allies had more armor, about 3,400 tanks to the Germans’ 2,700. But Allied armor was mostly spread out among the infantry divisions, whereas all German tanks were concentrated into the ten panzer divisions.

Only in the air was Germany clearly superior: 4,000 first-line aircraft to 3,000 Allied planes. Worse, many Allied planes were obsolete and their bombers were designed to strike area or general objectives, not targets on the battlefields as were the 400 Stukas. The French thought they could use medium bombers as “hedge hoppers” to attack enemy troops. But when they tried it they found the bombers were extremely vulnerable to ground fire.

The French had only sixty-eight Dewoitine 520 fighters, their only craft with performance approaching that of the 520 Messerschmitt 109 Bfs. The British Royal Air Force held back in England the competitive Spitfire, though a few Hurricanes were in France and could challenge the Messerschmitt on only slightly inferior terms.

While the Germans were placing their faith in a new type of warfare based on fast-moving tanks supported by dive-bombers, the French (and to a large degree the British) were aiming to fight World War I all over again.

The French army was by far the strongest challenge, but its doctrine required a continuous front, strongly manned by infantry and backed up by artillery. The French expected the enemy to attack this front fruitlessly and wear down his strength. Only when the enemy was weakened and finally stopped did doctrine permit the French army to go over to the offensive. An attack was always to be a bataille conduite, literally “battle by guidance” but translated as “methodical battle” by the British. This system had been worked out in the late stages of World War I and refined ever since. It was slow in the extreme. French doctrine prohibited action until the commander had perfect information about his and the enemy’s forces, a process requiring extensive, time-consuming reconnoitering.

When the infantry attack started it had to come behind a massive artillery barrage. The foot soldiers could advance only 1,500 meters before stopping to allow the artillery to shift its fires. After several such bounds, they had to stop until the guns could be moved forward.

All this required a great deal of time. A training exercise in 1938, for example, took eight days of preparation for an attack that was to last two days.

Guderian, who was fully aware of the enemy’s battle system, was confident that the speed of the panzer advance would preclude the French from ever having time to mount a counterattack. The situation would change by the hour, and the French would never catch up. This meant to Guderian that the panzers did not have to worry about their flanks. They would reach the English Channel and victory before the French could even begin to react.

The German high commanders, who thought more like their French opposite numbers than like Guderian, were not so sure. Out of these conceptual differences much conflict would emerge.

3 THE DEFEAT OF FRANCE

TRUE TO THEIR PLAN, THE GERMANS DELIVERED THEIR FIRST BLOWS IN HOLLAND and northern Belgium. The strikes were so sensational and convincing that they acted like a pistol in starting the Allies’ dash forward.

In the first great airborne assault in history, 4,000 paratroops of Kurt Student’s 7th Airborne Division descended from the early morning sky May 10, 1940, into “Fortress Holland” around The Hague, Rotterdam, and Utrecht. The sudden appearance of this force in the heart of the Dutch defensive system staggered every Allied commander. The Dutch had expected to defend this region for a couple of weeks, long enough for the French to join them and hold it indefinitely. Immediately after Student’s parachutists grabbed four airports near Rotterdam and The Hague, Theodor von Sponeck’s 22nd Infantry Air-Landing Division (12,000 men) started arriving by transport aircraft.

The Germans tried to seize The Hague and the government by a coup de main, but failed, taking many casualties. They were, however, able to capture key bridges in the Dordrecht-Moerdijk-Rotterdam area and hold them until the 9th Panzer Division broke through the frontier and rushed to the bridges on May 13, 1940, eliminating all possibility of resistance.

On the same day the Germans carried out the first major aerial atrocity of World War II: their aircraft rained bombs down on the undefended center of Rotterdam, killing about a thousand civilians and terrorizing the country. Two days later, the Dutch capitulated. Their army had scarcely been engaged.

Another dramatic scenario played out at the bridges over the Maas (or Meuse) River and the Albert Canal around Maastricht—fifteen miles inside the Dutch frontier. The bridges here were vital to the Germans to get their panzers across and into the open plains of Belgium beyond. Dutch guards were certain to blow the spans the moment they heard the Germans had passed the frontier. The Germans, accordingly, decided on a surprise strike.

In addition, a way had to be found to neutralize the Belgian fort Eben Emael about five miles south of Maastricht. It guarded the Albert Canal and the Maas just to the east. Eben Emael, constructed of reinforced concrete and housing casemated 75-millimeter and 120-millimeter guns, had been completed in 1935 and was regarded as virtually impregnable. There was only one undefended part of the fort: the flat roof. This was Eben Emael’s undoing.

Adolf Hitler personally selected paratroop Captain Walter Koch to lead the mission. His force included a platoon of army combat engineers, under Lieutenant Rudolf Witzig.

Early on May 10, 1940, twenty-one ten-man gliders drawn by Junker 52 transports pulled off from fields near Cologne. Over Aachen at 8,000 feet, the gliders unhooked and slowly descended over Dutch territory, ten landing beside four key bridges, and nine landing right on top of the Eben Emael roof. Lieutenant Witzig was not among them. His and another glider’s ropes snapped, and his glider had to be retrieved by another Ju-52. Before Witzig arrived, his sergeant, Helmut Wenzel, had taken charge and set explosive charges in gun barrels, casemates, and exit passages. In moments the German engineers had incapacitated the fort and sealed the 650-man garrison inside. The next day German infantry arrived, and the fort surrendered.

While this attack was going on, storming parties under Captain Koch seized four Albert Canal bridges before the astonished defenders could destroy them.

Читать дальше

![Джонатан Димблби - Barbarossa - How Hitler Lost the War [calibre]](/books/385421/dzhonatan-dimblbi-barbarossa-how-hitler-lost-the-w-thumb.webp)