In the early spring, special operations removed dangerous Soviet penetrations and freed a number of German forces that had been surrounded.

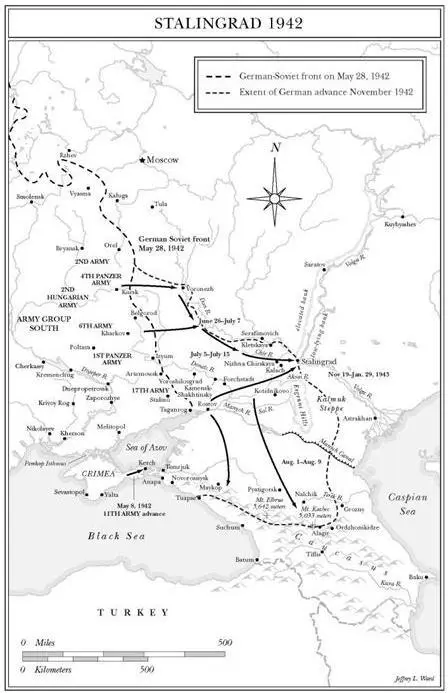

Manstein launched a surprise thrust in the Kerch peninsula of the Crimea, May 8–18, which shattered three Russian armies and yielded 169,000 prisoners. This induced the Russians, under Semen K. Timoshenko, to make a premature diversionary attack in the Kharkov region to the north, giving the Germans an opportunity to thrust into their flank in the Donetz region. These battles, May 17–22, used up a great part of the Soviet forces from the Volga to the Don. The Germans captured 239,000 men, and destroyed more than a thousand tanks and two thousand cannons.

Manstein opened a third offensive against the Crimean fortress of Sevastopol on June 7, a gruesome confrontation that lasted three weeks. After storming Soviet positions, Germans captured 97,000 enemy soldiers, but 100,000 got away on ships of the Soviet Black Sea fleet.

Soviet morale declined from these defeats, and Stalin commenced a new drive to get the western Allies to establish a second front to draw off German forces. Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov signed an alliance with Britain on May 26, but this brought no guarantees and not many supplies.

Although army chief of staff Franz Halder tried to get Hitler to remain on the defensive in 1942, Hitler insisted on a summer offensive in the south (Operation Blue). Hitler called for Army Group South under Fedor von Bock to advance in two directions—eastward across the Don to Stalingrad on the Volga with one army, and southward to the oil fields of the Caucasus with four.

The campaign opened on June 28, 1942. Hermann Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army with two armored corps (800 tanks and self-propelled assault guns) achieved complete surprise, broke through the Russian lines, and seized Voronezh in a few days. The army then swung southeast down the west bank of the Don through ideal tank country—open rolling plains, dry and hard from summer drought, broken occasionally by deep valleys in which villages were tucked away. Infantry divisions attacked simultaneously and secured the flanks and rear of the armor. Hoth hoped to trap many Russians in the great bend of the river.

While Hoth’s fast troops rolled down the Don, 17th Army (Richard Ruoff) and 1st Panzer Army (Ewald von Kleist) seized Rostov on July 23.

Nevertheless, Russian commanders were able to withdraw numerous divisions across the Don south of Rostov and at Kalach, forty-five miles west of Stalingrad. Hitler blamed Bock and removed him from command.

Hitler now made an irretrievable error. He had concluded, because of the initial success of the offensive, that Soviet strength had been broken, and diverted Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army south to help Kleist’s 1st Panzer Army cross the lower Don to open a path to the Caucasus.

“It could have taken Stalingrad without a fight at the end of July,” Kleist said after the war. “I did not need its aid, and it merely congested the roads I was using. When it turned north again, a fortnight later, the Russians had gathered sufficient forces at Stalingrad to check it.”

Panzer leader Friedrich-Wilhelm von Mellenthin voiced the opinion of nearly all senior officers in this campaign. When Stalingrad was not taken in the first rush, it should have been shielded with defensive troops and not attacked directly.

“By concentrating his offensive on a great city and resorting to siege warfare,” Mellenthin wrote, “Hitler was playing into the hands of the Russian command. In street warfare the Germans forfeited all their advantages in mobile tactics, while the inadequately trained but supremely dogged Russian infantry were able to exact a heavy toll.”

On the day Rostov fell, Hitler set up two new army groups, with new goals. Army Group A (17th and 1st Panzer Armies) under Wilhelm List was to seize the mountain passes and oil fields of the Caucasus, while Army Group B (2nd, 6th, and 4th Panzer Armies) under Maximilian von Weichs was to build a defense along the Don, drive to Stalingrad, block off the land bridge between the Don and the Volga, and interdict traffic on the Volga.

In his original plan, Hitler intended four armies to press into the Caucasus, while one went toward Stalingrad. Now three armies marched on Stalingrad—an objective of infinitely less importance than the oil fields—while two armies drove into the Caucasus.

This was lunacy to every professional soldier, and Halder protested to Hitler. But the Fuehrer paid no attention, and also ignored evidence of powerful Soviet formations to the east of the Volga and in the Caucasus. Hitler transferred his headquarters to Vinnitsa in Ukraine, and took over direct command of the southern part of the front.

Army Group A swept over the lower Don into the Caucasus. The 17th Army seized Krasnodar, crossed the Kuban River, and penetrated the thickly wooded west Caucasus Mountains to Novorossiysk on the Black Sea. Elsewhere, mountain troops could not drive the Russians out of the high passes. Kleist’s 1st Panzer Army, slowed by fuel shortages, captured the oil field of Maykop, 200 miles south of Rostov, though not before the Russians had destroyed it. But Kleist did not have the strength to drive to Batum, Tiflis, and Baku, which would have secured the Caucasus.

In Army Group B, 2nd Army fought around Voronezh, while the huge 6th Army with twenty divisions under Friedrich Paulus pressed toward Stalingrad. The ever-lengthening north flank of 6th Army along the Don was covered by the Hungarian 2nd Army, the Italian 8th Army, and the Romanian 3rd Army, while the Romanian 4th Army held a thin line in the Kalmuk steppe south of Stalingrad. The flanks thus were guarded by extremely weak forces, since none of the allies had good equipment or adequate training.

Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army had now turned northeast and was pressing through Elista across the steppe toward Stalingrad. About fifty miles south of the city, Hoth’s attack broke down against fierce resistance by the Soviet 57th and 64th Armies.

Originally the Soviet high command, Stavka, did not plan to hold Stalingrad. It intended to withdraw Red forces east of the stream, so the Germans would be forced to overwinter on the unprotected steppe. But the unexpected splitting of the German offensive called for new decisions. Stalin removed Timoshenko from command in the south and ordered Andrei I. Eremenko to take over and keep the city.

Stalingrad was no fortress. The old city of Tsaritsyn (Stalin had named it after himself in 1925) was surrounded by a jumble of old wooden structures, barrack-like apartments, industrial installations, and railroad switchyards sprawling fifteen miles along the west bank of the river, and two to four miles back from it. Above the apartments and factories reared water towers and grain silos. Numerous balkas (dry ravines or gullies with steep banks) and railway embankments eased the defense, as did the high western bank of the Volga and, west of the city, a twenty-nine-mile arc of woods, a mile wide at its thickest, protecting against dust and snow-storms. In August 1942 Stalingrad held about 600,000 people, including refugees.

Eremenko had five armies, some hard-hit. But Stalin issued a “Ni shagu nazad!” (“Not a step back!”) order on July 28, and reinforcements began to arrive. Eremenko got eleven divisions and nine Guards brigades, supplied from dumps on the steppe east of the river. He mobilized 50,000 civilian volunteers into a “people’s guard,” assigned 75,000 inhabitants to the 62nd Army, organized factory workers into rifle companies and tank units (using T-34s driven right off the floor of the tractor plant Dzherhezinsky where they were made), assigned 3,000 young women as nurses and radio operators, and sent 7,000 boys aged thirteen to sixteen to army formations. But Eremenko did order the evacuation of those too old or young to fight—200,000 crossed over to the east bank in a three-week period.

Читать дальше

![Джонатан Димблби - Barbarossa - How Hitler Lost the War [calibre]](/books/385421/dzhonatan-dimblbi-barbarossa-how-hitler-lost-the-w-thumb.webp)