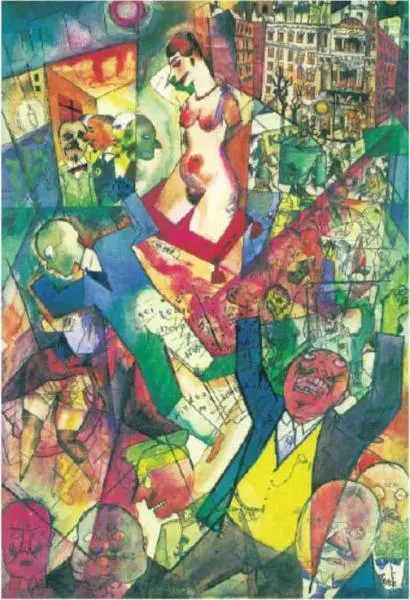

Neither a source of fine entertainment nor a legitimate venue for intercourse, the Nachtlokals were lambasted as embarrassingly ersatz. But they provided Berlin with a psychic opening. Wild sex and all-night antics could be made anywhere. In private flats, hotel rooms, and rented halls, drug parties and nude “Beauty Evenings” were constantly announced and held. A gala atmosphere enveloped 1919 and 1920. The entire city transformed into a Nachtlokal for its liberated youth and still comfortable bourgeoisie.

The stimulants and fashions changed too. “Radium cremes” and tincture of yohimbé bark from West Africa, which augmented female and male desire, were manufactured in little shops and advertised in Galante monthlies. Seamstresses—mostly White Russians and former noblewomen—added a Berlin touch; they reinvigorated Flapper-era couture by utilizing materials associated with male fetishism and slashed dresses to mimic pornographic renderings. Exhibitionism competed with voyeurism as the city’s outrageous draw. Every single Berlin night before June 1920 began to resemble New Year’s, or Sylvester’s, Eve.

When the Weimar Republic signed the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 there was a mutual understanding that the emotional issues of German national boundaries, demilitarization, and war reparations would be negotiated at future parleys. But the subsequent conferences in the early Twenties proved disastrous for the Republic. Angered by German bickering that rejected their resolute demands for immediate disarmament and sharply redrawn borders, French and English politicians tripled the amount Germany would owe the victors—six billion gold marks in raw materials and industrial goods to be paid over a 42-year period.

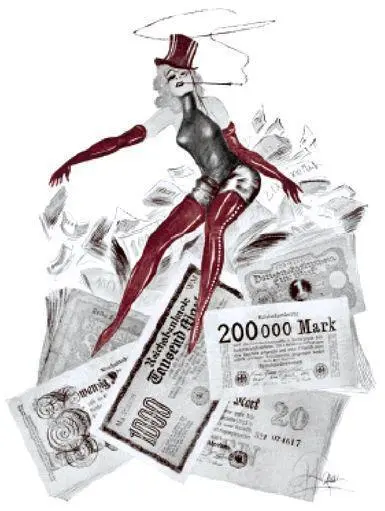

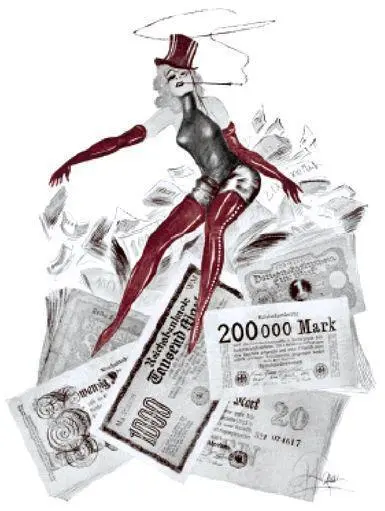

The terms of the 1921 Reparation Act more than bankrupted the German federal treasury; it ensured the end to any hopes for a stable commercial life in the struggling Republic. Its currency would eventually become worthless. But the scope of the monetary freefall was not clear at first. Seven marks bought one American dollar in January 1921, then the rate of exchange tumbled to 550/1 in August. In the summer of 1922, a mere dollar traded for 7,500 German marks. By January 1923, the official rate was 22,400/1, then in May the mark slid further to 54,300 per dollar. An all-time low was reached on October 12, 1923 when the once-vaunted German note plummeted to the staggering equation of 4.2 billion marks to the dollar.

Paul Kamm, 1923

Germans on fixed incomes and pensioners lost everything in those years. Once again wartime barter was a favored means of livelihood. Religious charities, like the Catholic Relief and the comically American Salvation Army, fanned out across Berlin. Crank indigenous cults also dished out thin soup with apocalyptic homilies.

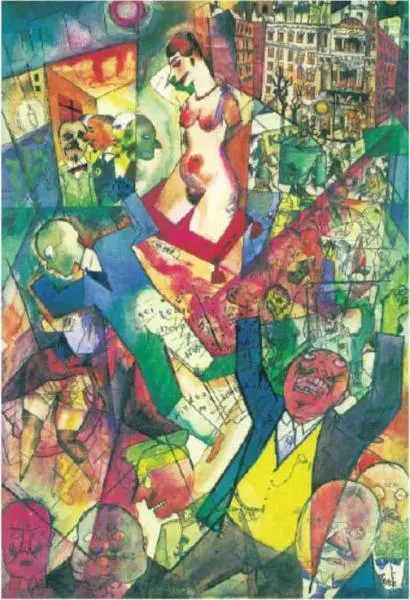

George Grosz, Down with Liebknecht , 1919

Most urban employees were paid by the day and scurried to exchange-banks in the morning before the value of their salaries declined by half in the late afternoon. German towns issued emergency paper scrip for its bewildered citizens; by the bitter fall of 1923, the nationwide legal tender was valued chiefly as a combustible for apartment furnaces. French newsreel-cameramen captured mustached Burgers hauling wheelbarrows of marks to pay taxes or purchase bread while their grandchildren built toy fortresses in alleyways, using stacks of the discarded bills as architectural blocks.

The Great Inflation complicated Berlin’s sexual folkways but did not really alter them. The so-called moral collapse had already occurred. Erotic amusements, prostitution, and narcotics were all readily available before the inflationary madness. But now the purveyors of commercial sex and other decadent offerings had a more acute economic incentive. Berlin was suddenly inundated with hard-currency tourists, looking for Jazz Age bargains. Swedes, Dutch, French, and detested hordes of Turks and Japanese flocked to the open city. Their modest assets in the form of kronen, guilders, francs, lira, and yen metamorphosed the plucky foreigners into multimillionaires the moment they disembarked at the Stettiner Bahnhof.

In postwar Paris, a traveler could engage the services of a streetwalker for five or six dollars; but during the Inflation in Berlin, five dollars could buy a month’s worth of carnal delights. The most exquisite blowjob or kinky dalliance with a 15-year-old never cost more than 30 cents, or 65 million 1923 marks. The widows of famous Wehrmacht generals rented their bodies and bedrooms for a few precious kronen. Even upright bourgeois couples exhibited themselves in marital embrace for a solid hour if anyone was interested in that kind of theatre.

Ilya Ehrenburg, the Russian writer, remembered going to a flat in a respectable neighborhood during the Inflation and discussing Dostoyevsky with the excited middle-class residents. After a glassful of lemonade mixed with spirits, the staid Berliners brought out their young, nubile daughters, who promptly executed a striptease before the shocked eyes of their celebrated guest. For American money, the mother proposed to the Communist ideologue, there was much more to be had that evening.

The Nachtlokals in particular teemed with non-German speaking thrill-seekers. For the newest clientele, humiliation and sexual degradation served as an equal attractant as the old Naked Dance revue itself. In one Lokal favored by Dutch vacationers, businessmen and their wives tossed foreign coins to any female German in attendance willing to strip completely nude. Outside the tourist hotels and downtown pensions, knowing gigolos and pretty boys, dolled up in rouge and mascara like wax mannequins, displayed their androgynous wares. To the merry-making Ausländer , Berlin was conducting a clearance sale in human flesh. Sex was everywhere and obtainable on the cheap. The Kaiser’s Germany, in the minds of many, was finally repaying its war debts.

Wolfram Kiesslich, Queen of Currency , 1922

On November 20th, 1923, the financial dementia lifted. The administration in Weimar introduced a new currency, the Rentenmark, which overnight stabilized the internal economy and Germany’s standing in the international marketplace. Worth about 20 cents, or one trillion marks, the Rentenmark was itself replaced by the Reichsmark in 1924. But confidence in Weimar governance, at least until 1929, was restored. The glorious period known as Germany’s “Golden Twenties” catapulted into history with champagne toasts and an intoxicating roar.■

Sex is the business of the town.

Anita Loos, 1923

There were men dressed as women, women dressed as men or little school-girls, women in boots with whips (boots and whips in different colors, shapes, and sizes, promising different passive or active divertissements). […] Young, well-washed, and pretty females were abundantly available. They could be had for the asking, sometimes without asking at all, often for the mere price of a dinner or a bunch of flowers: shopgirls, secretaries, White Russian refugees, nice girls from decayed good families. Some of them pathetically wept on the rumpled bed after making love when they accepted money.

Читать дальше