Dr. Hirschfeld had a different take on these puzzling enactments. He also studied hundreds of cross-dressers in Berlin (but with surprising empathy) and theorized that the irrepressible urge to costume oneself with articles of clothing identified with the opposite sex fell into a new and independent erotic category. In 1908, he coined the word to describe this “intermediate sexual” behavior as transvestism and further popularized the provocative theory with his influential text, Transvestites: the Erotic Drive to Cross-Dress .

According to Hirschfeld, only 35% of the male and female transvestites he observed could be classified as practicing homosexuals; an equal percentage were, more or less, congenital heterosexuals, with the remaining 30% being split between cross-dressers who exhibited bisexual tendencies and “auto-monosexuals,” a narcissistic type for whom the very act of pasting up an artificial beard or sporting false breasts before a mirror accompanied an autorerotic rush. Even among the cross-dressing bisexuals, Hirschfeld found a strong psychological tilt toward heterosexuality: they were mainly married men, who reluctantly allowed themselves to be penetrated by Cellar-Masters because of a desperate need to wear feminine clothing during intercourse. By engaging in this particular activity, bisexual transvestites claimed that they had maintained a heterosexual fidelity to their unknowing spouses.

Hirschfeld culled from the literature of cross-dressers and explored the wide, and naturally hidden, world of transvestite life in Berlin. In doing so, he was able to devise discrete typologies and innovative classifications for gender reidentification and illusionism. These were based on the intensity of the erotic fixation and its relationship to sexual release (some male transvestites, for instance, desperately needed female attire to maintain erectile status; others suffered from spontaneous ejaculation when lipstick or other female makeup was forcibly applied to their faces); the duration and scope of activity (“Silk panties worn only after office-hours, sir?”); the full, partial, open, or veiled nature of the clothing or behavior (“What do you feel when the young woman seated next to you realizes that your arm is not that of a man’s?”); and significantly, how the altered gender appearance transformed the transvestite into a more authentic, sexually charged and psychologically fulfilled individual.

Kamm, Training

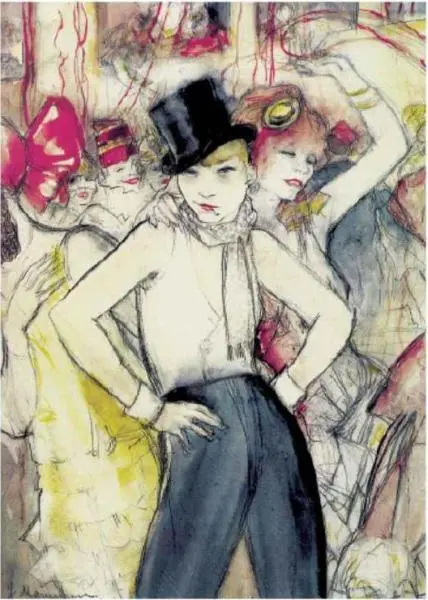

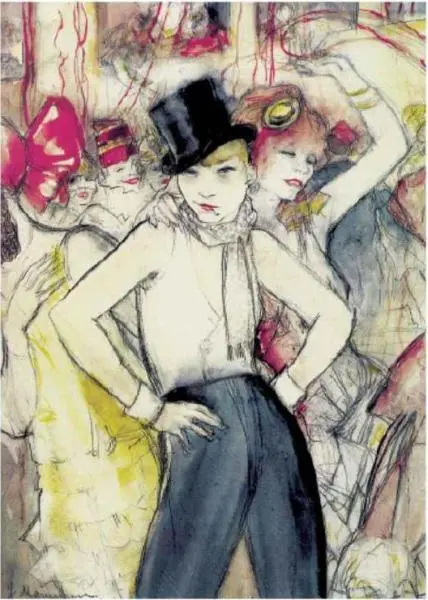

Mammen, Masked Ball, 1928

At his Institute of Sexology, which opened in 1919, Hirschfeld employed several transvestite maids and servants of both genders. Hundreds of Berlin cross-dressers, including Nazi Party members, received private counseling there, filling out cards that described their erotic compulsion in minute, near-pornographic detail. And it was long rumored (and reported in the reactionary press) that the otherwise strait-laced medical physician and cultural celebrity himself metamorphosed into a charming full-figured Auntie at Institute tea parties and secluded, smutty evening gatherings.

The Transvestite Demi-Monde

Despite Hirschfeld’s scientific announcements, male and female transvestites were universally seen as a colorful subset of queer Berlin. Cross-dressed heterosexuals, except as one-time Doll-Boys or girlish Line-Boys , remained closeted and invisible to the general public. Straight and bisexual transvestites, reportedly the majority, had little interest in socializing or even communicating with one another. Der dritte Geschlect (“The Third Sex”), Friedrich Radszuweit’s upbeat periodical for “ordinary” [straight?] cross-dressers, couldn’t find a reading public and folded after two or three issues in 1929.

Heterosexual Ladies , according to Hirschfeld, often married women with pronounced masculine traits (often themselves partial cross-dressers). Shame and fear of social ridicule kept straight transvestites’ distinct peccadillos indoors or coyly sublimated except during Carnival season. Undecided or borderline types were, of course, a lucrative cash cow for Minette callgirls, who graciously offered their special therapeutic services.

The normal life of queer male transvestites, the obvious drag queens and divas, who frequently lived as couples, was further complicated by Paragraph 168, a Prussian statute that forbade the appearance of cross-dressers on Berlin’s thoroughfares. This gave rise to private transvestite Dielen and bars, where patrons entered as dowdy men and women and then re-emerged from the bustling restrooms as splendid specimens of the opposite sex. On occasion—and as a favor to crime reporters, usually their drinking buddies—Berlin vice commissioners staged phony raids on these establishments, maliciously forcing the transvestites out into the street, where they were subject to instant arrest and a battery of tabloid paparazzi.

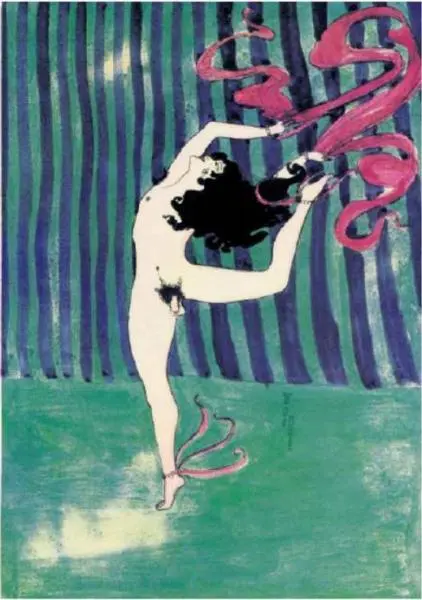

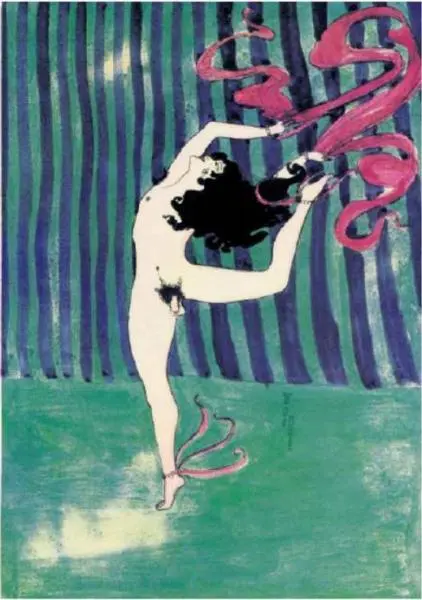

Expressive drawing by Voo-Doo, a Lady dancer

Private lounges and nightclubs formed the nucleus of Berlin transvestite social activity and interaction. The first club that catered to cross-dressers, the “Hannemann,” opened in 1892 on Alexanderstrasse, and welcomed both men and women. It was also a Boy Bar, and its mixed queer clientele typified a communal openness of same-sex pursuits in the Wilhelmian era. Frequented by off-duty German soldiers, low-level bureaucrats, Line-Boys , and hard-drinking Bubis , it was soon replaced by the infamous “Mikado Bar” and the “Bülow-Kasino” (on Bülowstrasse).

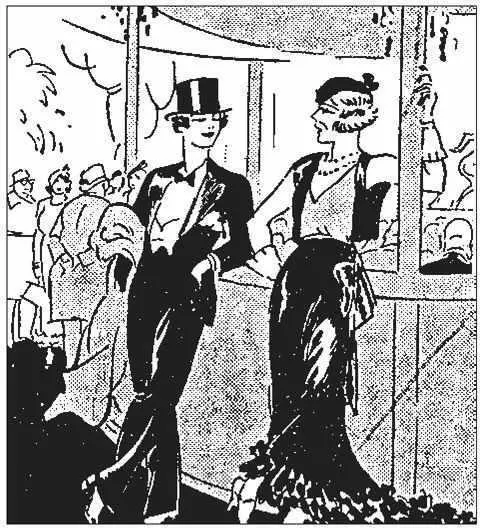

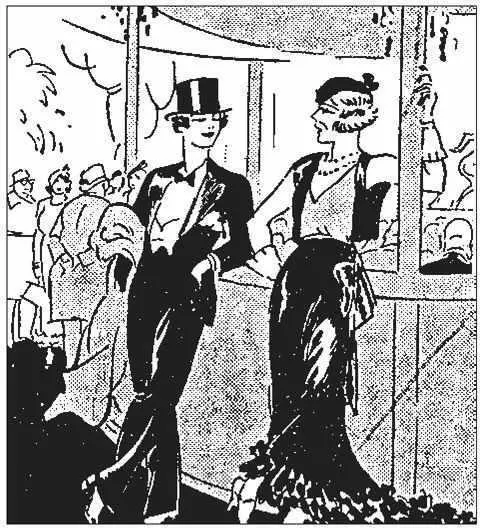

Lustige Blätter , 1932: Left figure: “Careful, I’m not a man!’ Right: “That’s okay, I’m not a woman.”

After the Collapse, drag queens appeared everywhere and added much to Berlin’s local color. The American writer Robert McAlmon, who visited the city during the desolate winter of 1923, reported, “Several Germans declared themselves authentic hermaphrodites [ sic —transvestites], and one elderly variant loved to arrive at the smart cabarets each time as a different type of woman: elegant, or as washerwoman, or a street vendor, or as a modest mother of a family. He was very comical and his presence always made for hilarity.”

Yet there was a corresponding pathetic side to that transgender illusionism: boys forced into the role of Situational female whores. Again McAlmon on a melodramatic note: “At nights along the Unter den Linden it was never possible to know whether it was a woman or a man in women’s clothing who accosted one. That didn’t matter, but it was sad to know that innumerable young and normal Germans were doing anything, from dope selling to every form of prostitution, to have money for themselves and their families, their widowed mothers and younger brothers and sisters.”

Transvestite acts, a standard feature of nineteenth-century German music-hall and variety, became more plentiful after 1919 and could be found in most gay cabarets and amusement halls. Performing before a mostly young, randy, and mostly liberated queer audience absolutely changed the outré nature of the enactments and their dramatic meanings. But growing political tension between the organized gay community and the theatrical drag queens and kings in the mid-Twenties forced a mass exodus of cross-dressers from homosexual Dielen to a different Berlin sensation, the public transvestite nightclub.

Читать дальше