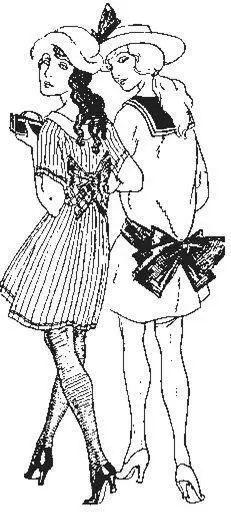

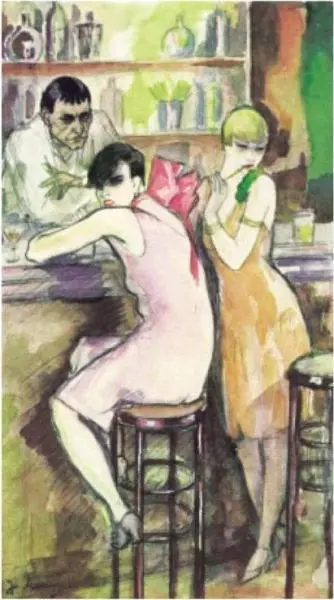

A Gougnette , 1926

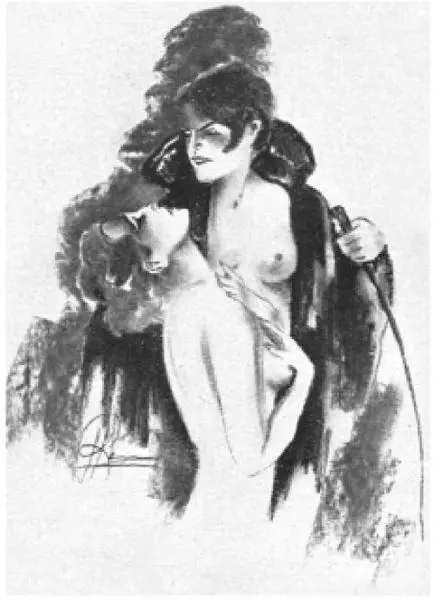

Finally, there was the Scorpion —a hopelessly evil femme fatale who took sick delight in the corruption of unworldly, ego-shattered girls. The menacing Scorpion was a made-up vampire who not only enjoyed the taste of virgin blood but the creation of man-hating progeny—“When she walked into the room, all the young women knew they were in abject moral danger!” The Scorpion was more than a defiling agent, a succubus who castrated men without their knowledge or physical presence, she was the living symbol of a new social order without erotic boundaries or familial conventions. Now heterosexual men had an additional day-to-day worry: sexual competition from females—especially from haughty aristocrats (particularly those with mixed Spanish or French lineage), vengeful widows recently returned from Paris or Budapest, and overly attentive Bohemian artistes.

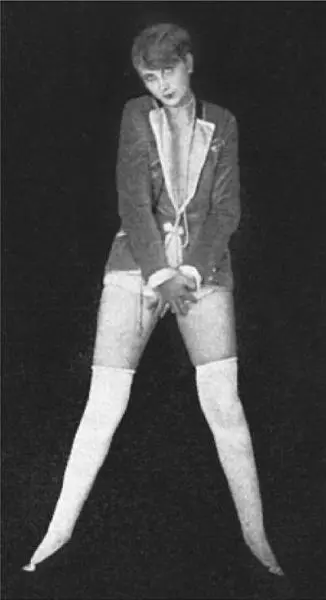

A 17-year-old Mädi , 1931

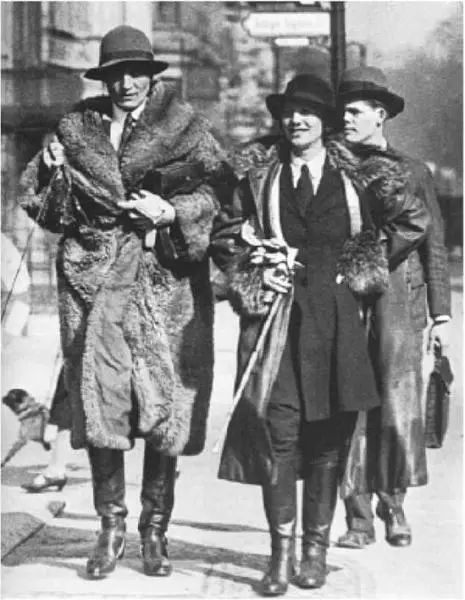

The artist Renée Sintenis and a Hot Sister

Around 1917, in the third year of the Great War, the iconography of lesbian life in Berlin underwent a sea change; suddenly, male graphic artists and writers presented women with same-sex cravings as desirable and darkly exotic. What was once universally considered sexually repulsive or threatening now provided an erotic jolt for heterosexuals, an amusing if mysterious (and therefore titillating) insight into another form of female sexuality. It was as if the lush German South Seas colonies—already lost in the war, together with their dusky, bare-breasted maidens—had come home to Berlin, an emotionally unsettled city, waiting for new voyeurist sensations.

Female secretaries, clerks, and daughters of shopkeepers, most of whom never even heard the word “Sapphic” before, started to spend sisterly time with one another, especially at night. An erotic community, independent of and unconcerned with men’s desires, was coalescing in the center of Europe. Interestingly, after the Armistice, foreign journalists remarked that post-Wilhelmian Berlin seemed different, that whole sections of the city, especially in the West and South, appeared to be devoid of sexually potent males, if one excluded pimps and other criminal riff-raff.

Kamm, The Sharper

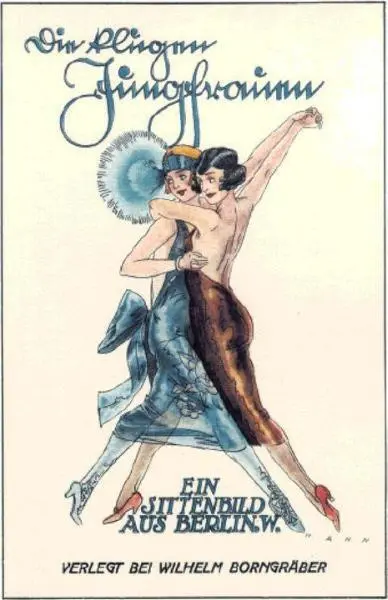

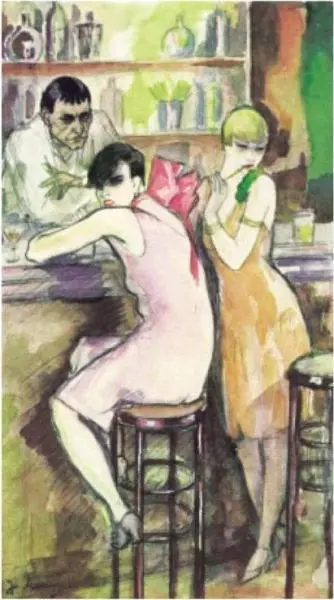

Long before Berlin’s lesbian heyday, turn-of-the-century Paris had infamous same-sex female bars and clubs, mostly tucked away in the Montmartre distinct, and chic balls where top-hatted women flaunted their tribadic lifestyles with shocking nonchalance. In fact, before the Collapse, Berlin lesbians looked to Paris as a cultural Mecca, a mythic capital of elegant liberation and delicious sexual ambiguity. French idioms, often mixed with Apache argot, haute street-urchin fashion, and teasing representations of Parisian female beauty percolated through the German queer nightlife in the early Twenties. But, by 1924, everything became reversed: it was the Parisian lesbians who longed for the freedom and sexual chaos of Berlin. The international center of female homosexuality slid eastward and changed languages.

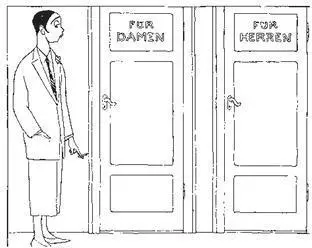

Karl Arnold, Which Door? 1925

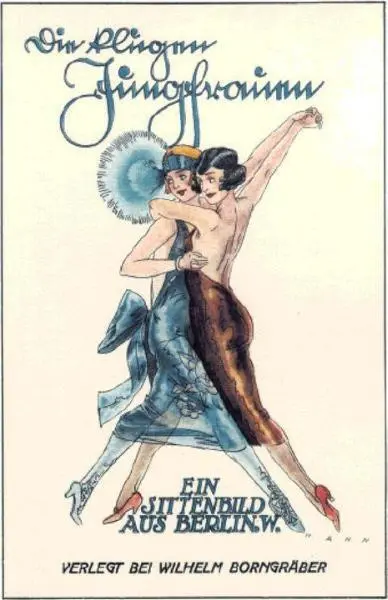

Lesbian Novel, The Clever Young Women , 1927

Trends in sexual behavior sometimes evolve in half-year cycles but the topography of lust rarely budges in any one decade. So the transformation from Paris to Berlin as the playground for women seeking the love of other women can only be described as extraordinary and unprecedented. Of course, Berlin’s growing status as a Hauptstadt of commercial sex had a part in it. Yet other factors should be considered.

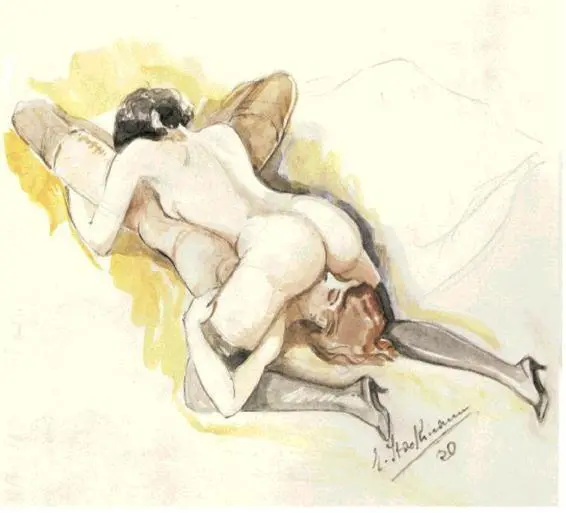

Schad, On the Bed , 1927

A Dodo

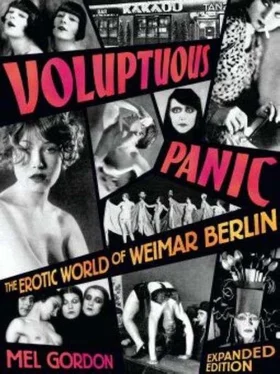

Berlin, the Lesbian Eldorado

Like its male counterpart, Berlin’s lesbian population was said to be enormous, large enough to support several dozen social clubs, two ice-skating leagues, a nudist retreat and three outdoor sports associations, six journals, and (as the guide books in the tourist hotels proudly announced) 85 nightclubs and lounges. But exactly how many women actively participated in Berlin’s lesbian subculture is difficult to assess. Magnus Hirschfeld estimated in 1930 that Berlin was home to some 400,000 lesbians, but that figure appears to be grossly inflated if we adhere to current definitions of sexual orientation. (Today not every female who engages in a short-term, same-sex relationship would accept the lesbian tag.)

Based on other criteria, like club memberships and magazine subscriptions, the number of Hot Sisters in Berlin (excluding Kontroll-Girls and Chontes ) was closer to 85,000. Paris, in the same years, could never tally more than 5,000 lesbians—again if one discounts female street prostitutes, of whom 25% were said to be constitutionally (or situationally) homosexual.

Nearly every social class and profession that allowed women was represented in the Berlin all-girl queer subculture. While most lesbians were employed in typically straight industries like government, publishing, entertainment, manufacturing, fashion, advertising, low-level commerce, and education, many worked exclusively in establishments that catered only to their own community. In other European cities, lesbianism was a choice allotted to just the very wealthy, glamorous, or patently avant-garde; in Berlin, any woman could pursue a same-sex lifestyle and find thousands of like-minded partners. Never in European history had women seeking the companionship of other women been so open and adventurous.

Hellmuth Stockmann, Lesbian Joy , 1920

Mammen, At the Bar (Salvation Army Girls), 1926

The German penchant for classification and uniforms further differentiated the Berlin lesbian milieu. Bubis , Dodos , Gamines , Garçonnes , Gougnettes , Hot Whores , Mädis , and Sharpers were the expressive orders tha one was supposed to inhabit by reason of sexual outlook and sexual affect. And even those types contained distinctive categories based on class status, political affiliation, perceived affluence, romantic interest, and appearance. The lesbian Dielen and associations, for the most part, appealed to specific couplings, for instance, only Dodos and Garçonnes , Sharpers and underclass Mädis , or like-minded Gamines .

Читать дальше