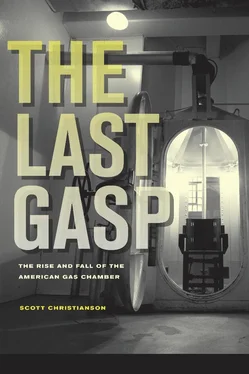

A few legal loopholes, however, remained until 1999, when at last the final American gas execution was carried out in Arizona. Ironically, the gas chamber’s final victim was a German national, and the World Court later condemned the execution as a violation of international law. Even after Auschwitz, it still took more than fifty years for gas-chamber executions to cease in the United States. At the close of the twentieth century, seventy-five years after the first lethal gas execution, the American gas chamber appeared to have reached the end of the line. One by one, the strange-looking steel-and-glass contraptions that had taken hundreds of lives were either consigned to museums or parking lots, or converted into lethal-injection chambers with hospital gurneys instead of chairs.

Even today some observers wonder if the gas chamber might be brought back. As I was writing this book, the Nebraska Supreme Court ruled in State v. Mata that execution by the electric chair is cruel and unusual punishment, finding that the “evidence here shows that electrocution inflicts intense pain and agonizing suffering.” 10Shortly thereafter the U.S. Supreme Court in Baze v. Rees considered whether Kentucky’s execution by a three-drug protocol of lethal injection violated the Eighth Amendment ban on cruel and unusual punishment. The action was historic because the only time the court had ever ruled directly on a method of execution was in 1878, when it upheld the use of the firing squad. Until Baze , the court had scrupulously avoided dealing with the nuts and bolts of specific execution methods. 11A leading capital-punishment scholar who testified in the case, Professor Deborah W. Denno, commented that the courts’ lack of Eighth Amendment guidance had “unraveled” the death penalty in the United States, contributing to a recent moratorium on executions as several states awaited the Supreme Court’s ruling. 12

But when the Supreme Court finally did rule, in April of 2008, validating the three-drug “cocktail,” Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. wrote for the 7–2 majority, “Simply because an execution method may result in pain, either by accident or as an inescapable consequence of death, does not establish the sort of ‘objectively intolerable risk of harm’ that qualifies as cruel and unusual.” Nevertheless, the ruling was so divided and convoluted that six individual justices wrote their own opinions, and legal observers concluded that the decision had generated more questions than answers, leaving open many possible future challenges to lethal injection and the death penalty in general. 13

So, with two of America’s dominant methods of execution subject to ongoing constitutional assault, some legal scholars have wondered if lethal gas might somehow reemerge to fill the vacuum. That doesn’t appear very likely—for reasons this book makes plain. Simply put, the gas chamber has lost its legitimacy.

The nature of a society’s system of criminal punishment reveals a great deal about that society’s values and power structure. Several books have examined the strange birth of the electric chair as a gimmick in the epic battle between Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse for dominance in the electrical power industry, and scores of articles and monographs probe the strange history of the even more medicalized alternative execution method of lethal injection (which was first implemented by the Nazis). 14Yet no such attention has been given to the American invention of the gas chamber, even though its unfolding is more illuminating and far-reaching. Surprisingly, even death-penalty scholars have neglected lethal gas. I hope that this book will stimulate further study.

Very few penologists have offered any hypotheses to explain why a society tends to adopt a specific form and degree of criminal punishment at a certain time. Some of the more persuasive theories have focused on the nature of the social structure in which the new punishment was introduced. Georg Rusche and Otto Kirchheimer in Punishment and Social Structure (1939) contended that fiscal motives have shaped the punishments developed in modern society, arguing that “every system of production tends to discover punishments which correspond to its productive relationships.” In another related work, Rusche, a Jewish Communist who had fled Nazi Germany, went so far as to claim that “the history of the penal system is… the history of relations [between] the rich and the poor.” 15

Theories of class struggle and capitalist profit seeking may help to explain the origin of the electric chair at the dawn of the electrical age in tumultuous industrial America. Such interpretations might also serve to account in part for the rise of the lethal chamber that had been championed by upper-class intellectuals for use against the “unfit” at a time when powerful chemical companies were dominating the modern industrial age, changing the nature of warfare, and championing the extermination of pests. But as far as the introduction of the gas chamber is concerned, Rusche and Kirchheimer’s approach seems to be too economically deterministic and neat to fully explain why and how the new execution method of lethal gas originated, spread, and died out.

What is clear is that neither punishment, the electric chair nor the gas chamber, arose simply as a response to crime, and indeed, there appears to have been little relationship between the nature of the penalties and the crimes that they were meant to punish. As Rusche and Kirchheimer have pointed out, “Punishment is neither a simple consequence of crime, nor the reverse side of crime, nor a mere means which is determined by the end to be achieved.” Their writing proved prophetic. The Nazis rendered individual guilt irrelevant. For the victims of the Holocaust, there was no connection between crime and punishment; the prisoners had not committed any criminal offense, and many were helpless children. According to Rusche and Kirchheimer, “Punishment must be understood as a social phenomenon freed from both its juristic concept and its social ends. We do not deny that punishment has specific ends, but we do deny that it can be understood from its ends alone.” 16

Rusche and Kirchheimer were rightly skeptical that humanitarian motives had ever been primarily responsible for determining changes in punishments such as methods of execution. Such wariness seems warranted, even though in the case of the lethal chamber much of the early impetus for its use came in the shape of calls for euthanasia that would end needless suffering and rid society of unwanted animals or persons who were deemed to be better off dead. Notions of “humane” treatment, humanitarianism, benevolence, tenderheartedness, philanthropy, and the effort to ease the pain and suffering of the oppressed gained considerable respectability in the early twentieth century—particularly as the world was reeling from the effects of the Great War and other traumas that were antithetical to these qualities.

This movement toward “humane executions” did not occur in a vacuum. At the precise moment when reformers in Nevada were enacting the “Humane Execution Law” to put criminals to death by means of poison gas, the renowned Alsatian philosopher and physician Albert Schweitzer was delivering his first lectures and publications introducing his philosophy of “reverence for life.” And in 1936, as intellectual support for gas euthanasia was high, the great humanist Schweitzer was characterizing the “modern age [as a time] when there are abundant possibilities for abandoning life, painlessly and without agony.” 17

The rise of the gas chamber also grew out of the birth of modern warfare, with its growing willingness to decimate civilian populations by chemical warfare and other means as part of a program of total war. Confronted by the fact that civilian noncombatants were relatively innocent and therefore shouldn’t be subjected to the same treatment as warriors, some military and political leaders advocated chemical attacks that would exterminate the enemy civilian population, but in a “kind” way that would reduce pain and suffering.

Читать дальше