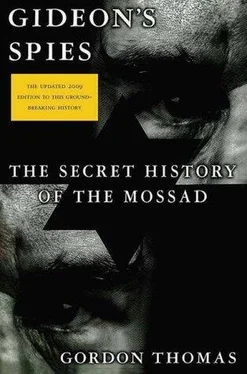

Gordon Thomas - Gideon's Spies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Gordon Thomas - Gideon's Spies» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Thomas Dunne Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gideon's Spies

- Автор:

- Издательство:Thomas Dunne Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-312-53901-6

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gideon's Spies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gideon's Spies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Gideon’s Spies

Gideon's Spies — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gideon's Spies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Cheryl Ben-Tov was a bat leveyha, one grade below a katsa. Born into a wealthy Jewish family in Orlando, Florida, she had seen her parents’ marriage end in a bitterly contested divorce. She found solace in religious studies, which led to her spending three months on a kibbutz in Israel. There she became immersed in Jewish history and the Hebrew language. She decided to remain in Israel. At the age of eighteen she met and fell in love with a Sabra, a native-born Israeli, called Ofer Ben-Tov. He worked for Aman as an analyst. A year after they met the couple were married.

Among the wedding guests were several high-ranking members of the Israeli intelligence community, including one from Meluckha, Mossad’s recruiting department. During the marriage feast he asked Cheryl the sort of questions any bride might expect. Was she going to go on working? Have a family at once? Caught up in the excitement of the celebrations, Cheryl had said her only plan was to try to find a way to give something back to her country, which had given her so much, referring to Israel as “family.” A month after she returned from her honeymoon, she received a call from the wedding guest: he said he had been thinking over what they had spoken about and maybe there was a way for her to help.

They arranged to meet at a café in downtown Tel Aviv. He astonished her by citing with complete accuracy her school grades, her family history, how she had met her husband. Perhaps sensing her anger at having her privacy invaded, he explained that all the information was in her husband’s file at Aman.

The recruiter understood that the relationship between himself and a potential recruit could often be tricky; it has been likened to a warlock initiating a neophyte into a secret sect with its special signs, incantations, and rites: it is the fellowship of Orpheus without a love of music. After telling Cheryl for whom he worked, the man delivered a set piece. Mossad was always on the lookout for people who wanted to serve their country. At the wedding she had compared Israel to a family. Well, Mossad was like that. Once you were accepted, you were part of its family, protected and nurtured. In return you served the family in any way asked of you. Was she interested?

Cheryl was. She was told she would have to undergo preliminary tests. During the next three months she took a number of written and oral examinations in various safe houses around Tel Aviv. Her high IQ—she consistently registered 140 in these tests—American background, general knowledge, and social skills made her an above-average recruit.

She was told she was suitable for training.

Before that, she had a further session with her recruiter. He told her she was about to enter a world in which she could share her experiences with no one, not even her husband. In such a lonely place, she would feel vulnerable to the corrupting lure of trust. But she must trust no one except her colleagues. She would be tutored in deceit, taught to use methods that violated every sense of decency and honor; she must accept new ways of doing things. She would find some of the acts she would be asked to perform highly unpleasant, but she must always put them in the context of the mission she was on.

The recruiter leaned across the table in the interview room and said there was still time for her to change her mind. There would be no recriminations; there should be no sense of failure on her part.

Cheryl said she was fully prepared to undergo training.

For the next two years she found herself in a world which, until then, had only been part of her favorite relaxation, going to the movies. She learned how to draw a gun while sitting in a chair, to memorize as many names as possible as they flashed with increasing speed across a small screen. She was shown how to pack her Beretta inside her pants, on the hip, and how to cut a concealed opening in her skirt or dress for easy access to the handgun.

From time to time, other recruits in her class left the training school; such departures were never a subject for discussion. She was sent on practice missions—breaking into an occupied hotel room, stealing documents from an office. Her methods were analyzed for hours by her instructors. She was aroused from her bed in the dead of night and dispatched on more exercises: picking up a tourist in a nightclub, then disengaging herself outside his hotel. Every move she made was observed by her tutors.

She was asked close questions about her sexual experiences. How many men had there been before her husband? Would she sleep with a stranger if her mission demanded? She answered truthfully: There had been no one before her husband; if she was absolutely certain that the success of a mission depended on it, then she would go to bed with a man. It would purely be sex, not love. She learned how to use sex to coerce, seduce, and dominate. She became especially good at that.

She was taught how to kill by firing a full clip of bullets into a target. She learned about the various sects of Islam and how to create a mishlashim, a dead-letter box. A day was spent perfecting a floater, a strip of microfilm attached to the inside of an envelope. Another was devoted to disguising herself by inserting cotton wadding in her cheeks to subtly alter the shape of her face. She learned to steal cars, pose as a drunk, chat up men.

One day she was summoned to the office of the head of the training school. He looked her up and down as if he were doing an inspection, checking off each item on a list in his mind. Finally he said she had passed.

Cheryl Ben-Tov was assigned as a bat leveyha working in Mossad’s Kaisrut department, which liaised with Israeli embassies. Her specific role was to provide cover—as a girlfriend or even as a “wife” for katsas on active service. She worked in a number of European cities, passing herself off as an American citizen. She did not sleep with one of her “lovers” or “husbands.”

Admoni personally briefed her on the importance of her latest mission: with Vanunu now located, it would be up to her to use her skills to entice him out of Britain. This time her cover would be that of an American tourist traveling alone around Europe after a painful divorce. To give that part of her story credibility, she would make use of details from her own parents’ separation. The final part of her story was to have a “sister” living in Rome. Her brief was to get Vanunu there.

On Tuesday, September 23, 1986, Cheryl Ben-Tov joined a team of nine Mossad katsas already in London. They were under the command of Mossad’s director of operations, Beni Zeevi, a dour man with the stained teeth of a chain-smoker.

The katsas were staying in hotels between Oxford Street and the Strand. Two were registered in the Regent Palace. Cheryl Ben-Tov was registered as Cindy Johnson in the Strand Palace, staying in room 320. Zeevi had rented a room at the Mountbatten, close to the one Vanunu occupied, 105.

He may well have been among the first to observe the mood changes in the technician. Increasingly Vanunu was showing signs of strain. London was an alien environment for someone brought up in the small-town life of Beersheba. And, despite the efforts of his companions, he was lonely and hungry for female companionship, for a woman to sleep with. Mossad’s psychologists had predicted that possibility.

On Wednesday, September 24, Vanunu insisted that his Sunday Times minders should allow him to go out alone. They reluctantly agreed. However, a reporter discreetly followed him into Leicester Square. There he saw Vanunu begin to talk to a woman. The newspaper would subsequently describe her as “in her mid-twenties, about five feet eight inches, plump, with bleached blond hair, thick lips, a brown trilby-style hat, brown tweed trouser suit, high heels and probably Jewish.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gideon's Spies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gideon's Spies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gideon's Spies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.