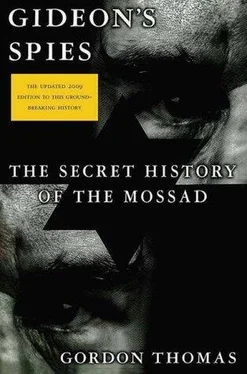

Gordon Thomas - Gideon's Spies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Gordon Thomas - Gideon's Spies» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Thomas Dunne Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gideon's Spies

- Автор:

- Издательство:Thomas Dunne Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-312-53901-6

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gideon's Spies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gideon's Spies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Gideon’s Spies

Gideon's Spies — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gideon's Spies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Watching over this ever-shifting bazaar of dealers and clients meeting over mint tea were officers from the Da’lrat Al-Mukhabarat Al-Amah, Iraq’s main intelligence organization, controlled by Sabba’a, Saddam Hussein’s almost as fearsome half-brother.

Some of the arms dealers had been in the hotel lobby on a very different day seven years before when their stunned hosts had told them that Israel, an enemy even more hated than Iran, had struck a powerful blow against Iraq’s military machine.

Since the formation of the Jewish state, a formal state of war had existed between Israel and Iraq. Israel had felt confident its forces could win a conventional war. But in 1977, Mossad discovered the French government, which had provided Israel with its own nuclear capability, had also given Iraq a reactor and “technical assistance.” The facility was Al-Tuweitha, north of Baghdad.

The Israeli air force began planning how to bomb the site before it became “hot” with the uranium rods in the reactor core. To destroy it then would cause widespread death and pollution and turn Baghdad and a sizable area of Iraq into an irradiated desert—and earn Israel global condemnation.

For these reasons, Yitzhak Hofi, then Mossad’s chief, opposed the raid, arguing an air strike would anyway result in a heavy death toll among the French technicians and would isolate European countries Israel was trying to reassure of its peaceful intentions. Bombing the reactor would also effectively end the delicate maneuvering to persuade Egypt to sign a peace treaty.

He found himself presiding over a divided house. Several of his department chiefs argued that there was no alternative but to neutralize the reactor. Saddam was a ruthless enemy; once he had a nuclear weapon, he would not hesitate to use it against Israel. And since when had Israel worried unduly about winning friends in Europe? America was all that mattered, and the whisper from Washington was that taking out the reactor would result in no more than a slap on the wrist from the administration.

Hofi tried a different tack. He suggested the United States should bring diplomatic pressure to bear on France to stop the export of the reactor. Washington received a curt rebuff from Paris. Israel then chose a more direct route. Hofi despatched a team of katsas to raid the French plant at La Seyne-sur-Mer, near Toulon, where the core for the Iraqi reactor was being built. The core was destroyed by an organization no one had ever heard of previously—the “French Ecological Group.” Hofi had personally chosen the name.

While the French began to build a new core, the Iraqis sent Yahya Al-Meshad, a member of its Atomic Energy Commission, to Paris to arrange the shipment of nuclear fuel to Baghdad. Hofi sent a kidon team to assassinate him. While the others patrolled the surrounding streets, two of them used a passkey to enter Al-Meshad’s bedroom. They cut his throat and stabbed him through the heart. The room was ransacked to look like robbery. A prostitute in an adjoining room told police she had serviced the scientist hours before his death. Later, entertaining another client, she had heard “unusual movement” in Al-Meshad’s room. Hours after she reported this to the police, she was killed in a hit-and-run incident. The car was never found. The kidon team caught an El Al flight back to Tel Aviv.

Despite this further blow Iraq, aided by France, continued with its bid to become a nuclear power. In Tel Aviv, the Israeli air force continued its own preparations while intelligence chiefs wrangled with Hofi over his continued objections. The Mossad chief found a challenge from an unexpected quarter. His deputy, Nahum Admoni, argued destroying the reactor was not essential but would teach “any other Arabs with big ideas a lesson.”

By October 1980, the debate preoccupied every cabinet meeting Menachem Begin chaired. Familiar arguments were revisited. Increasingly, Hofi became a lone voice against the attack. Nevertheless he struggled on, producing well-written position papers, knowing he was writing his own professional obituary.

Admoni increasingly made no secret of his contempt for Hofi’s position. The two men, who had been close friends, became cold colleagues. Nevertheless, it took a further six months of bitter conflict between the embattled Mossad chief and his senior staff before the general staff approved the attack on March 15, 1981.

The attack was a tactical masterpiece. Eight F-16 fighter-bombers, escorted by six F-15 fighter-interceptors, flew at sand-dune level across Jordan before streaking toward Iraq. They reached the target at the planned moment, 5:34 P.M. local time, minutes after the French construction staff had left. The death toll was nine. The nuclear plant was reduced to rubble. The aircraft returned unharmed. Hofi’s career in Mossad was over. Admoni replaced him.

Now, on that April morning in 1988, the arms dealers in the lobby who, seven years before, had commiserated with their shocked hosts on the Israeli attack—before selling Iraq improved radar systems—would have been stunned to know that in the hotel a Mossad agent was quietly noting their names and what they were selling.

Earlier that Friday, business in the lobby had been briefly interrupted by the arrival of Sabba’a Al-Tikriti, the head of Iraqi secret police, accompanied by his own Praetorian phalanx of bodyguards. Saddam Hussein’s half brother strode to the elevator, on his way to a rooftop suite. Waiting there was the tall, buxom prostitute specially flown in from Paris for his pleasure. It was highly paid, high-risk work. Some of the previous whores had simply disappeared after Sabba’a had finished with them.

The security chief left in midafternoon. Shortly afterward, from a suite adjoining the prostitute’s, emerged a tall young man dressed in a blue cotton jacket and chinos. He was good-looking in a slightly effete way, with a nervous habit of stroking his mustache or rubbing his face that somehow increased his vulnerability.

His name was Farzad Bazoft. In the details on the hotel registration form—a copy of which had been routinely sent to Sabba’a’s ministry—Bazoft had described himself as the “chief foreign correspondent” for The Observer, the London-based Sunday national newspaper. The description was inaccurate: only the newspaper’s staff reporters on overseas assignments were allowed to call themselves “foreign correspondents.” Bazoft was a freelance journalist who, for the past year, had contributed to The Observer several stories with Middle Eastern themes. Bazoft had admitted to reporters from other news organizations who were also on this trip to Baghdad that he always passed himself off as The Observer ’s chief foreign correspondent on trips to cities like Baghdad because it ensured he had the best available hotel room. The harmless fiction was seen as another example of his endearing boyishness.

Unknown to his newspaper colleagues, there was an altogether darker side to Bazoft’s personality, one that could possibly jeopardize them if they were ever suspected of being involved in the real reason he was in Baghdad. Bazoft was a Mossad spy.

He had been recruited after he had arrived in London three years before from Tehran, where his increasingly outspoken views on the Khomeini regime had put his life in danger. Like many before him, Bazoft found London alien and English people reserved. He had tried to find a role for himself in the Iranian community in exile, and for a while his considerable knowledge of the current political structure in Tehran made him a welcome guest at their dinner tables. But the sight of the same familiar faces soon palled for the ambitious and restless young man.

Bazoft began to look around for more excitement than dissecting a piece of news from Tehran. He began to establish contacts with Iran’s enemy, Iraq. In the mid-1980s there were a large number of Iraqis in London, welcome visitors because Britain saw Iraq not only as a substantial importer of its goods, but also as a nation which, under Saddam Hussein, would subdue the threatening Islamic fundamentalism of the Khomeini regime.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gideon's Spies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gideon's Spies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gideon's Spies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.