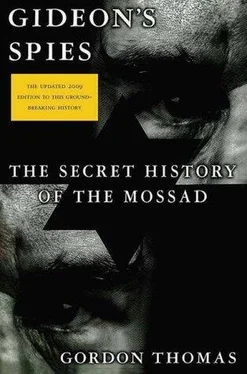

Gordon Thomas - Gideon's Spies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Gordon Thomas - Gideon's Spies» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Thomas Dunne Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gideon's Spies

- Автор:

- Издательство:Thomas Dunne Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-312-53901-6

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gideon's Spies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gideon's Spies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Gideon’s Spies

Gideon's Spies — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gideon's Spies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In Iran, the spiritual home of Shkaki, the mullahs declared a day of national mourning. In Tel Aviv, asked to comment on the death, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin said: “I am certainly not sad.”

A few days later, on November 4, 1995, Rabin was assassinated at a Tel Aviv peace rally, close to the safe house where his order to execute Shkaki had been prepared. Rabin had died at the hands of a Jewish fanatic, Yigal Amir, who in many ways had the same ruthless qualities the prime minister had so admired in Mossad.

Yitzhak Rabin, the hawk who had become a dove, the powerful political leader who had come to realize the only chance of peace in the Middle East was, as he once misquoted his favorite book, the Bible, “is to turn our swords into ploughshares and till the soil with our Arab neighbors,” was murdered by one of his own people because he failed to accept that his Jewish enemies would behave with the same ferocity as his old Arab foes had done—both groups determined to destroy his vision of the future.

In 1998 there were forty-eight members in the Mossad kidon unit, six of them women. All were in their twenties and superbly fit. They lived and worked outside Mossad headquarters in Tel Aviv, based in a restricted area of a military base in the Negev Desert. The facility could be adapted to approximate a street or a building where an assassination was to take place. There were getaway cars and an obstacle course to negotiate.

The instructors included former unit members who supervised practice with a variety of guns, and taught how to conceal bombs, administer a lethal injection in a crowd, and make a killing appear accidental. Kidons reviewed films on successful assassinations—the shooting of President John F. Kennedy, for example—and studied the faces and habits of scores of potential targets stored on their own highly restricted computer and memorized the constantly changing street plans of major cities as well as air and seaport layouts.

The unit worked in teams of four who regularly flew abroad on familiarization trips to London, Paris, Frankfurt, and other European cities. There were also occasional trips to New York, Los Angeles, and Toronto. During all of these outings a team was always accompanied by instructors who assessed their skills in setting up an operation without drawing attention to themselves. Targets were chosen from local sayanim volunteers who were only told they were taking part in a security exercise designed to protect an Israeli-owned facility; a synagogue or bank were usually given as the reason. Volunteers found themselves pounced upon in a quiet street and bundled into a car, or had their homes entered in the middle of the night and awoke to find themselves peering down a gun barrel.

Kidons took these training exercises very seriously, for every team was aware of what was known as the “Lillehammer Fiasco.”

In July 1973, at the height of the manhunt for the killers of the Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics, Mossad received a tip that the “Red Prince” Ali Hassan Salameh, who had planned the operation, was working in the small Norwegian town of Lillehammer as a waiter.

Mossad’s then director of operations, Michael Harari, had put together a team not drawn from the kidon unit; its members were scattered across the world chasing the remaining terrorists who had carried out the Munich killings. Harari’s team had no field experience, but he was confident his own background as a katsa in Europe was sufficient. His team included two women, Sylvia Rafael and Marianne Gladnikoff, and an Algerian, Kemal Bename, who had been a Black September courier before being browbeaten by Harari into becoming a double agent.

The operation had run into disaster from the outset. The arrival of a dozen strangers in Lillehammer, where there had not been a murder for forty years, aroused speculation. The local police began to watch them. Officers were close by when Harari and his team shot dead a Moroccan waiter named Ahmed Bouchiki, who had no connection to terrorism and did not even physically resemble Salameh. Harari and some of his squad managed to escape. But six Mossad operatives were captured, including both women.

They made full confessions, revealing for the first time Mossad’s assassination methods and other equally embarrassing details about the service’s clandestine activities. The women, together with their male colleagues, were charged with second-degree murder and received jail sentences of five years each.

Returning to Israel, Harari was fired and the entire Mossad undercover network in Europe of safe houses, dead-letter boxes, and secret phone numbers was abandoned.

It would be six years before Ali Hassan Salameh would finally die in the operation masterminded by Rafi Eitan, who said, “Lillehammer was an example of the wrong people for the wrong job. It should never have happened—and must never happen again.”

It did.

On July 31, 1997, the day after two Hamas suicide bombers killed 15 and injured another 157 people in a Jerusalem marketplace, Mossad chief Danny Yatom attended a meeting chaired by Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu. The prime minister had just come from an emotional press conference at which he had promised that he would never rest until those who planned the suicide bombings were no longer a threat.

Publicly, Netanyahu had appeared calm and resolute, his responses to questions measured and magisterial; Hamas would not escape retribution, but what form that would take was not a matter for discussion. This was the “Bibi” from Netanyahu’s days on CNN during the Iraqi war, when he had earned repeated praise for his authoritative assessments of Saddam Hussein’s responses and how they were viewed in Israel.

But on that stifling day, away from the cameras and surrounded only by Yatom and other senior intelligence officers and his own political advisers, Netanyahu offered a very different image. He was neither cool nor analytical. Instead, in the crowded conference room adjoining his office, he frequently interrupted to shout he was going to “get those Hamas bastards if it’s the last thing I do.”

He added, according to one of those present, that “you are here to tell me how this is going to happen. And I don’t want to read in the newspapers anything about ‘Bibi’s’ revenge. This is about justice—just retribution.”

The agenda had been set.

Yatom, well used to the mercurial mood swings of the prime minister, sat silently across the table as Netanyahu continued to bluster. “I want their heads. I want them dead. I don’t care how it’s done. I just want it done. And I want it done sooner rather than later.”

Tension deepened when Netanyahu demanded that Yatom provide a list of all Hamas leaders and their present whereabouts. No prime minister had ever before asked for sensitive operational details at such an early stage. More than one person in the room thought that “Bibi was sending a signal he was going to be hands-on for this one.”

It deepened the unease among some Mossad officers that the service was being forced to come too close to Netanyahu. Perhaps sensing this, Yatom told the prime minister that he would provide the list later. Instead, the Mossad chief suggested that it was “time to look at the practical side of things.” Locating the Hamas leaders would be “like searching for individual rats in a Beirut sewer.”

Once more Netanyahu erupted. He didn’t want excuses; he wanted action. And he wanted it to start “here and now.”

After the meeting ended, several intelligence officers were left with the impression that Bibi Netanyahu had crossed the fine line where political expediency ended and operational requirements took over. There could not have been a man in the room who did not realize that Netanyahu badly needed a public relations coup to convince the public the act-tough-on-terrorism policy that had brought him into office was not just empty rhetoric. He had also gone from one scandal to another, each time barely wriggling clear by leaving others to carry the blame. His popularity was at an alltime low. His personal life was all over the press. He badly needed to show he was in charge. To deliver the head of a Hamas leader was one surefire way.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gideon's Spies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gideon's Spies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gideon's Spies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.