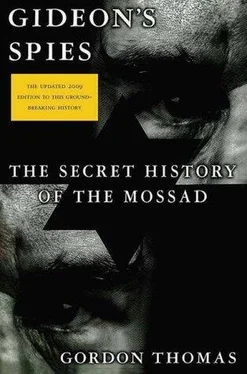

Gordon Thomas - Gideon's Spies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Gordon Thomas - Gideon's Spies» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Thomas Dunne Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gideon's Spies

- Автор:

- Издательство:Thomas Dunne Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-312-53901-6

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gideon's Spies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gideon's Spies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Gideon’s Spies

Gideon's Spies — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gideon's Spies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

According to at least one well-placed Israeli intelligence source, Rafi Eitan had received a phone call from Yatom reinforcing the need to stay well clear of the United States for the foreseeable future.

Rafi Eitan did not need to be told how ironic it would be if he fell victim to the very technique that had made him a legend—the kidnapping of Adolf Eichmann. Even worse would be to be quietly killed by one of the methods that had burnished his reputation among men who saw assassination as part of the job.

CHAPTER 6

AVENGERS

On a warm afternoon in mid-October 1995, a technician of Mossad’s internal security division, Autahat Paylut Medienit (APM), used a hand-operated scanner to check an apartment off Pinsker Street in downtown Tel Aviv for bugging devices. The apartment was one of several safe houses Mossad owned around the city. The search was an indication of the sensitivity of the meeting shortly to take place there. Satisfied the apartment was electronically clean, he left.

The apartment’s furniture could have come from a garage sale; nothing seemed to match. A few cheaply framed pictures hung on the walls, views of the Israel tourists liked to visit. Each room had its own separate unlisted telephone. In the kitchen, instead of domestic appliances, were a computer and modem, a shredder, a fax, and, where an oven would be, a safe.

Usually the safe houses were dormitories for trainees from the Mossad school for spies on the outskirts of the city while they learned street craft: how to tail someone or themselves avoid surveillance; how to set up a dead-letter box, or exchange information concealed inside a newspaper. Day and night the streets of Tel Aviv were their proving ground under the watchful eye of instructors. Back in the safe houses, the lessons continued: how to brief a katsa going to a target country; how to write special-ink letters or use a computer to create information capable of being transmitted in very short bursts on specified frequencies.

An important part of the seemingly endless hours of training was how to form relationships with innocent, unsuspecting people. Yaakov Cohen, who worked for twenty-five years as a katsa under deep cover around the world, believed one reason for his success was lessons learned in those lectures:

“Everyone and anyone became a tool. I could lie to them because truth was not part of my relationship with them. All that mattered was using them for Israel’s benefit. From the very beginning, I learned a philosophy: Do what was right for Mossad and for Israel.”

Those who could not live by that credo found themselves swiftly dismissed from the service. For David Kimche, regarded as one of Mossad’s best operatives:

“It’s the old story of many think they are called, few are chosen. In that way we are a little like the Catholic church. Those who remain, develop bonds which will carry them through life. We live by the rule of ‘I help you, you help me.’ You learn to trust people with your life. No greater trust can ever be given by one person to another.”

By the time every man or woman who had access to the safe houses graduated to the next group, that philosophy had been engraved on their minds. They were now katsas departing on a mission or returning to be debriefed. Known as “jumpers” because they operated overseas on a short-term basis, they inevitably called the safe houses “jump sites.” Too much imaginative description was frowned upon by their superiors.

Finally, the safe houses were used as meeting places for an informer, or to interrogate a suspect who had the potential to be recruited as a “mole.” The only indication of their numbers has come from a former Mossad junior officer, Victor Ostrovsky. He claimed in 1991 there were “about 35,000 in the world; 20,000 of these operational and 15,000 sleepers. ‘Black’ agents are Arabs, while ‘white’ agents are non-Arabs. ‘Warning agents’ are strategic agents used to warn of war preparations: a doctor in a Syrian hospital who notices a large new supply of drugs and medicines arriving; a harbor employee who spots increased activity of warships.”

Some of these agents had received their first instructions in a safe house like the one that had been meticulously checked for bugs on that October afternoon. Later in the day, a handful of senior members of Israel’s intelligence community would meet around the apartment’s dining-room table to sanction an assassination that would have the full approval of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin.

In the three years he had been in that office, Rabin had attended a growing number of funerals for the victims of terrorist attacks, each time walking behind pallbearers and watching grown men weep as they listened to the committal prayer. With each death he had conducted “a funeral in my own heart.” Afterward he had again read the words from the prophet Ezekiel: “And the enemy shall know I am the Lord when I can lay down my vengeance on them.”

This was not the first time Rabin’s vengeance had been felt; Rabin had himself on more than one occasion participated in an act of revenge. Most notable had been the assassination of Yasser Arafat’s deputy, Khalil Al-Wazir, known throughout the Arab world and on Mossad’s Honeywell computer as Abu Jihad, the voice of holy war, who lived in Tunisia. In 1988, Rabin had been Israel’s defense minister when the decision was taken in the same apartment off Pinsker Street that Abu Jihad must die.

For two months Mossad agents conducted an exhaustive reconnaissance of Abu Jihad’s villa in the resort of Sidi Bou Said on the outskirts of Tunis. Access roads, points of entry, fence heights and types, windows, doors, locks, defenses, the routing employed by Abu Jihad’s guards: everything was monitored, checked, and checked again.

They watched Abu Jihad’s wife play with her children; they came alongside her as she shopped and went to the hairdresser. They listened to her husband’s phone calls, bugged their bedroom, listened to their lovemaking. They calculated distances from one room to another, found out what the neighbors did, when they were at home, and logged the makes, colors, and registrations of all the vehicles that came and went from the villa.

The rule for preparing an assassination Meir Amit had laid down all those years ago was constantly in their minds: Think like your target and only stop being him when you pull the trigger.

Satisfied, the team returned to Tel Aviv. For the next month they practiced their deadly mission in and around a Mossad safe house near Haifa that matched the target villa. From the time they would enter Abu Jihad’s house, it should take the unit just twenty-two seconds to murder him.

On April 16, 1988, the order was given for the operation to go ahead.

That night several Israeli air force Boeing 707s took off from a military base south of Tel Aviv. One carried Yitzhak Rabin and other high-ranking Israeli officers. Their aircraft was in constant touch by safe radio with the execution team already in position and led by an operative code-named “Sword.” The other aircraft was crammed with jamming and monitoring devices. Two more 707s acted as fuel tankers. High above the villa the fleet of aircraft circled, following every move on the ground through a secure radio frequency. A little after midnight on April 17 the airborne officers heard Abu Jihad had returned home in the Mercedes Yasser Arafat had given him as a wedding gift. Prior to that the hit team had set up sensitive listening devices able to hear everything inside the villa.

From his vantage point near the villa, Sword announced into his lip mike that he could hear Abu Jihad climbing the stairs, going to his bedroom, whispering to his wife, tiptoeing to an adjoining bedroom to kiss his sleeping son, before finally going to his study on the ground floor. The details were picked up by the electronic warfare plane—the Israeli version of an American AWAC and relayed to Rabin’s command aircraft. At 12:17 A.M. he ordered: “Go!”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gideon's Spies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gideon's Spies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gideon's Spies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.