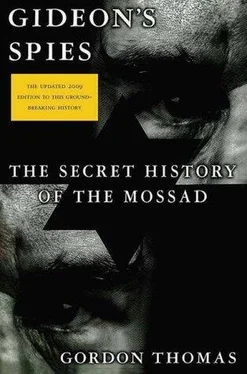

Gordon Thomas - Gideon's Spies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Gordon Thomas - Gideon's Spies» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Thomas Dunne Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gideon's Spies

- Автор:

- Издательство:Thomas Dunne Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-312-53901-6

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gideon's Spies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gideon's Spies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Gideon’s Spies

Gideon's Spies — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gideon's Spies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In the closing weeks of 2005, Meir Dagan opened a staff meeting with what Sergei Kondrashov, a retired KGB chief of counterintelligence, had said, that if the KGB had been forced to chose between what a Russian mole in the U.S. administration reported and a subscription to The New York Times, he would believe the newspaper any day. Dagan reminded them that until Porter Goss became the CIA director, the agency evaluated intelligence reports on a simple scale: ABCD for the reliability of the source and 1234 for how accurate the information was. A1 meant the source was unchallengeable and the information unquestioningly true. B2 indicated the source was good, and the intelligence was very probably true. Category D4 meant the source was totally unreliable and the information demonstrably false. Dagan had paused and said that Goss had spoken to a number of his deputy directors who admitted they had rarely seen A1 and only a small number of D4s. The great majority of reports crossing their desks were designated C3—the source had been reliable in the past and so his information was possibly true. Dagan had looked around the conference table and said that logically this meant a usually reliable source was sometimes also unreliable and the information described as possibly true could just as well be untrue. He reminded them that for Mossad good intelligence was always required to contain the caveat as Saint Paul glimpsed heaven—“through a glass, darkly.” It was an indication of how Mossad must continue to face threats as the world became a global village and the demands made on an intelligence service grew daily. Gone were the clear divisions between the Soviet Union and the West. Terrorism, international money laundering, ruthless dictators, and ethnic conflicts had all changed the traditional role of spying and counterintelligence. In the desperate hunt for information to combat the new targets, intelligence services had been forced to operate in unfamiliar areas.

As 2005 drew to a close, the war on terrorism had not achieved many of its targets. While Saddam had been captured, Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda remained a potent threat. Mossad’s analysts had concluded that capturing or killing bin Laden would do nothing to eliminate al-Qaeda; it had a well-defined command structure ready to replace him, and the organization itself was increasingly focused on spreading its ideology to inspire others and imitate what had been achieved on September 11, 2001. Madrid, London, Bali, and Amman were all signposts on the road to further massacres. The analysts estimated al-Qaeda was now entrenched in sixty countries, truly a hydra-headed monster.

No one could have said what the effect would have been from the power play between Ayman al-Zawahiri, a fanatic with a scholar’s beguiling mind, and the clinically insane Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. Both grasped the importance of using the Internet as a virtual base from which to proselytize and provide instruction. It meant that al-Qaeda training camps could attract jihadists who had already acquired the essential hatred of the United States, Britain, and, above all, Israel. The time recruits needed to be in the camps could be shortened, reducing the risk of them being caught in an air strike or a ground assault. Ironically, al-Zarqawi would be killed by a carefully planned air attack by the United States in Iraq in 2006.

Increasingly, state-sponsored terrorism had flourished and would continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Countries like Syria, North Korea, and Iran had calculated the risk of punishments they could face—and concluded they were worth the risk. In Damascus, Pyongyang, and Tehran the collective view was that not even the United States would contemplate starting a global war by launching a nuclear bomb against those states; neither would Israel, for all its posturing with nuclear submarines posted in the Gulf of Oman, be likely to launch a preemptive strike. So Islamic radicalism continued to grow, its sponsors knowing they would face, at most, no more than conventional military strikes. Sanctions, as Saddam Hussein’s Iraq had demonstrated, did not work.

Al-Qaeda had also recognized that terrorism was war by another name, but was not treated as acts of war. Pakistan could arm Kashmiri terrorists to attack the Indian Parliament in 2001; Iranian-trained Saudis blew up the U.S. military base at Khobar in 1996; and Syrian-born members of Hamas bombed Israeli buses as they had done for years: yet none of these actions were treated as acts of war to be declared on the sponsoring states.

The danger of terrorism, as Meir Dagan had regularly lectured new members of Mossad, was its cost effectiveness. It cost little to produce a suicide bomber. One attack can create havoc, forcing a government to use its resources—manpower and technology—to try and capture the terrorists. A Mossad analyst had once calculated (for the author) that “one terrorist cost as much as a hundred expensively trained men to catch or capture him or her.”

Into this already complex situation there was the ever-expanding role of the Chinese secret service, CSIS. China has a tradition of espionage that reaches back over twenty-five hundred years. But never had its activities been more far-reaching than today.

Since the theft of nuclear secrets from Los Alamos, CSIS had continued to expand its activities in the United States. Many of China’s accredited diplomats in its Washington embassy, various consulates, and trade missions throughout the United States were either full-time intelligence officers or directly linked to the service. The FBI estimated that in 2005 the number of CSIS agents and informers was larger than any other foreign intelligence service operating within the country. Since Los Alamos they had between them obtained, either by theft or deception, an estimated $35 million worth of secrets, mostly from technology companies working in or for the defense industry. FBI Director Robert Mueller, had ordered that all the firms be briefed on improving their security and that organizers of technology conferences, which had always attracted Chinese scientists, were instructed on “how to recognize a possible CSIS agent.” Universities were asked to provide details of courses “and other interests” of the thirty thousand Chinese students on their campuses after the FBI established that CSIS had paid for an increasing number to study in America; many were attending postgraduate courses at universities like UCLA, Harvard, Yale, and Stanford. After graduating, often in computer or science-related subjects, they had applied for jobs at companies with sensitive defense contracts. A former senior FBI officer, Ted Gunderson, who had worked on counterterrorism out of the Los Angeles field office, told the author: “The students are taught how to steal, photocopy, and return valuable blueprints and secret contracts and smuggle them out past the security guards. The material is often on microfilm inserted into a tooth cavity or swallowed to be excreted later in one of the many safe houses CSIS has around the country.”

Meir Dagan’s now-close relationship with Porter Goss enabled the backdoor channel to be used to provide details of what Mossad knew about CSIS activities in the United States. Both intelligence chiefs knew much of the material was too politically sensitive to pass on to the White House or the State Department until there was absolute proof of espionage.

In October 2005, a Los Angeles–based katsa informed Tel Aviv that a CSIS spy ring in California was about to courier to China disks containing ultrasecret details about U.S. weapons systems, which had been encrypted and hidden behind tracks of music CDs and the latest movie releases. A Mossad sayanim who worked for the same high-security defense contractor, Power Paragon, in Anaheim, California, which employed a member of the spy ring, Chi Mak, had become suspicious and informed his katsa . The sayanim was told to keep watch. In weeks, he had provided sufficient details for the katsa to alert Tel Aviv.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gideon's Spies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gideon's Spies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gideon's Spies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.