Izvolsky was a gambler. From his first days in office he favored a policy of diagonals: keeping Russia balanced between the German-Austrian and the Anglo-French ententes. He regarded neither partnership as inherently friendly to Russia’s interests, and was correspondingly suspected of insincerity, if not duplicity, by everyone else. It was scarcely surprising that Izvolsky found attractive the prospects of a knight’s move in the Balkans. It might put relations with Austria on a firmer, more positive basis. It could fix Izvolsky’s place in history. And it would show the rest of Europe that Russia was not to be despised. It was Izvolsky who on July 2, 1908, suggested to Aehmenthal an exchange of favors. Russia would support Austria’s direct annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, provinces she had ruled de facto since 1879. Austria would support Russia’s claim to move her warships freely through the Dardanelles. This right, enjoyed by no other nation, would be useful in itself and was a potential stepping stone to further pressures on the Ottoman Empire. Executed over Serbia’s head, the agreement would also demonstrate the will of the great powers most directly involved in the Balkans to control that situation themselves, and not resign it to secondary actprs.

The negotiations incorporated an essential imbalance: territory against a promise, provinces against words. Aehrenthal was able to make the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina a fait accompli, while Izvolsky roamed the chanceries of Europe, vainly seeking international consent to a Russian move that had been unacceptable since before the Crimean War. Nor did he find support at home. From left to right, Russian public opinion interpreted the Bosnian annexation as a disaster. Izvolsky’s aim of acquiring free passage through the straits by diplomacy was ridiculed in the newly created Duma by deputies of all political stripes indignant over the apparent betrayal of the racial cause involved in abandoning two Slavic-inhabited provinces to Teuton rule. Professors, editors, and generals seethed with indignation. Students in Moscow and St. Petersburg took to the streets in protest—a shock to authorities used to seeing them on the other side. Premier P. A. Stolypin, the man on whose shoulders rested the entire fragile framework of domestic reforms that was tsarism’s response to the disasters of 1905, threatened openly to resign unless Nicholas denounced Izvolsky’s bargain. To make matters worse, Serbia denounced the agreement, spoke openly of war unless somehow compensated for the annexation, and turned to Russia demanding support for this policy.

Much of the domestic criticism of Izvolsky reflected the Aesopian politics characteristic of Russia long after 1917, with parties and pressure groups using questions of foreign policy as lead-ins or stalking horses for the domestic issues that were their real concerns. Nevertheless, particularly in its weakened state, the autocracy could not afford to ignore entirely the legitimations conferred by public opinion. On the other hand, Russia in the aftermath of her defeat by Japan was militarily in no shape to confront anyone—even Austria. Faced with paying lost bets from an empty pocket, the best Izvolsky could do was to try to placate the Serbs on one hand while on the other demanding a European conference to discuss the entire issue. 1

Then Germany moved into the driver’s seat. The eruption of the long-quiet Balkans was anything but welcome in the context of her increasing economic and political involvement in southeastern Europe and the Ottoman Empire. Bismarck had been able to present himself as a disinterested mediator with at least some credibility. Wilhelmian Weltpolitik had led to an increasing suspicion of German intentions in the Near East by Austria as well as Russia. Germany was developing a different set of friends and enemies, encouraging an Italian connection Austria found increasingly unpalatable, fostering an arms race that Austria could not sustain, and competing with Austria for economic influence in the Near East. In rejecting Izvolsky’s call for a conference, Aehrenthal was simultaneously challenging the German government’s commitment to its Austrian alliance. 2

From Austria’s perspective, the results were positive—almost too positive. Fatalism, an acceptance of what Wolfgang Mommsen calls the topos of inevitable war, was an increasingly important rhetorical flourish among German policymakers. Yet it was less a faith than an attitude, a mixture of Weltschmerz and fin de siècle posturing. It might be fashionable in diaries and drawing rooms. It might be given a retrospective edge through postwar hindsight. But despair hardly dominated the working days of men who remained too completely the children of an age of progress to wait for disaster. Instead they did their best to avert the worst. 3

German policy was significantly influenced by Izvolsky’s apparent isolation in his own country. Tsar Nicholas took pains to assure the German military plenipotentiary, navy Captain Paul von Hintze, of his continued desire for good relations. Ferdinand von Monts, German ambassador to Rome, reported his Russian colleague’s insistence that the mood in St. Petersburg was absolutely peaceful. The Russian had sharply criticized Izvolsky’s behavior, even though he was a close relative. From the Petersburg embassy, Friedrich von Pourtalès quoted the Russian war minister: Serbia was completely powerless to start a war; France was too weak to think of anything but the defensive; and Russia wished no war with Germany over Serbia’s pretensions. 4

For Bülow this was an opportunity to recover ground lost in 1905. Rejecting encouragement from within his foreign office to mediate directly between Izvolsky and Aehrenthal, he instead instructed Hintze and Pourtales to stress both Germany’s current support for Austria and Russia’s current isolation as the direct consequences of a “demonstrative” Russian rush into England’s embrace. Why, Bülow asked, should not the kaiser be hurt at Russia’s abandonment of a Germany that, under constant threat to her own security and constant pressure from Europe’s radicals, had been such a faithful and unrequited supporter for so many years? And what were the probable results if Aehrenthal released the documents showing Izvolsky’s original encouraging of the annexation? What price then the rhetoric of Slavic unity and European solidarity? 5

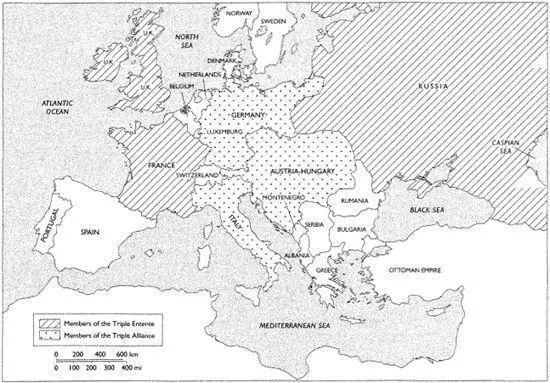

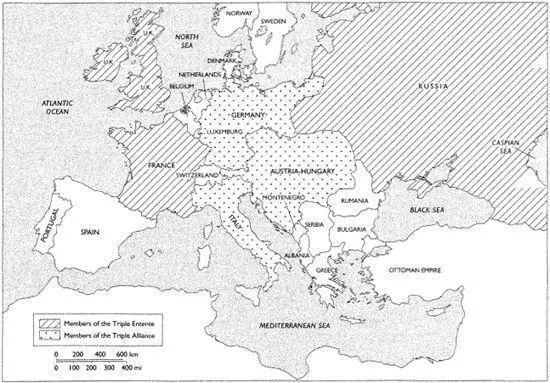

Europe, Summer 1914

Aehrenthal had originally begun the annexation adventure to improve relations with Russia, not destroy them. Yet neither was he blind to the implications of Russia’s continued waffling on the Serbian question. Russia, he insisted, must give up her “mad claim” to being Serbia’s protector. Serbia was a local power, unentitled to compensation except as a concession. 6

From a German perspective, Aehrenthal’s position did no more than reflect the blind alley in which Russia found herself. The German consul in Moscow, for example, reported that the Russian government could hardly expect popular support for war on Serbia’s behalf. Panslavism was a dead issue in central Russia. Domestic corruption and abuse of police power were far livelier themes. Witte too, in a long conversation with Pourtalès, began by stressing the centuries of tradition and the deep idealism behind the concept of Slavic brotherhood. But when pressed to declare if Russia had a real interest in helping the Serbs, Witte said decisively, “No.” 7

As early as December 11 Izvolsky had informed the German ambassador that he wanted war at no price. “What should I do now?” he asked despairingly. When told he needed only to reach an agreement with Austria-Hungary, the Russian foreign minister bristled that it was impossible to negotiate with Aehrenthal. Now, with February giving way to March, Bülow was convinced the crisis had gone on beyond reason or profit for anyone. With neither Russia nor Austria willing to move decisively, the risks of an accidental explosion were growing with each passing week. Sir Arthur Nicolson was among the firmest supporters of close Anglo-Russian cooperation. Yet even he observed the “strange inconsistency” of insisting that a rival “is not to advance beyond a certain point if it be not intended to prevent him doing so at all costs… I fear that Russia may some day find herself in the dilemma of having to decide either to afford material assistance to the victims of Austria… or to abdicate permanently her position as the great Slav protector and guardian.” 8The situation resembled nothing so much as a tightly covered pot of boiling water. Either the heat must be reduced or a safety valve introduced.

Читать дальше