Rudy Anderson’s widow gave birth to a baby girl seven and a half months later.

Because of the seven-hour time difference, it was already well after midnight in Moscow. Nikita Khrushchev was resting at his villa on the Lenin Hills, with its panoramic view of the Kremlin and the winding Moscow River. He had returned home late from the office and asked for his usual nighttime drink, tea with lemon. He suggested that his wife and son drive out to their weekend retreat outside Moscow in the morning. He had summoned other Presidium members to meet with him at a government villa nearby. As soon as he was free, he would join the rest of his family at the dacha.

Around 1:00 a.m., Khrushchev got a series of calls from his aides. A telegram had just arrived from the Soviet Embassy in Havana relaying the letter from Fidel Castro predicting an American attack on Cuba in the next twenty-four to seventy-two hours. It also contained a dramatic plea. Hearing the letter read to him over the phone, Khrushchev concluded rightly or wrongly that Castro was advocating a preemptive nuclear strike against the United States. He interrupted his aide several times to clarify certain passages in the text.

Khrushchev viewed Castro’s message as a “signal of extreme alarm.” Earlier in the day, he had decided there was still time to negotiate a face-saving compromise with Kennedy. The Americans seemed to be wavering. A U.S. invasion of Cuba appeared unlikely at a time when Washington was responding to Soviet diplomatic feelers through the United Nations. But what if Castro was right? Khrushchev had instructed Soviet troops to come to the aid of their Cuban comrades in the event of an American attack. There would inevitably be many Soviet casualties. It would be very difficult, perhaps impossible, to limit the fighting to Cuba.

Another factor to be considered was Castro’s fiery personality. Khrushchev did not doubt that his Cuban friend was extraordinarily courageous, and willing to sacrifice his life for his beliefs. He liked and admired Fidel enormously, but he was also aware of his headstrong nature. Castro reminded the onetime Ukrainian peasant of “a young horse that hasn’t been broken.” It was necessary to tread very carefully with such a creature. The man Cubans called el caballo was “very spirited.” He needed “some training” in order to turn him into a reliable Marxist-Leninist.

The idea that the Soviet Union would be the first to use nuclear weapons was completely unacceptable to Khrushchev, however much he threatened and blustered. Unlike Castro, he had no illusions about the USSR’s ability to win a nuclear war. The United States had more than enough nuclear weapons both to sustain a first strike and to wipe out the Soviet Union. The Cuban obsession with death and self-sacrifice startled Khrushchev, who had seen more than his share of destruction and suffering. He understood, perhaps for the first time, just how differently he and Castro “viewed the world” and valued human life. As Khrushchev saw it, “We are not struggling against imperialism in order to die” but to achieve the long-term “victory of communism.” To be Red and dead was to miss the point.

And yet here was this Cuban revolutionary talking blithely about launching a nuclear strike against the United States. Having lived through World War I, the Russian Civil War, and the Great Patriotic War, Khrushchev shuddered to think what would happen if he followed Castro’s advice. America would obviously sustain “huge losses,” but so would the “socialist camp.” Even if Cubans fought and “died heroically,” their country would be destroyed in the nuclear crossfire. It would be the start of a “global thermonuclear war.”

The jolt of Castro’s letter was soon followed by another shock. At 6:40 p.m. Washington time, 1:40 a.m. Sunday in Moscow, the Pentagon announced that an American military reconnaissance aircraft had gone missing over Cuba and was “presumed lost.” The Pentagon statement did not make clear whether the plane had been shot down, but the implications for the Kremlin were deeply disturbing. While Khrushchev had authorized his commanders on Cuba to fight back in self-defense, he had not ordered attacks on unarmed reconnaissance planes. He wondered whether Kennedy would be willing to “stomach the humiliation” of the loss of a spy plane.

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

Cat and Mouse

5:59 P.M. SATURDAY, OCTOBER 27

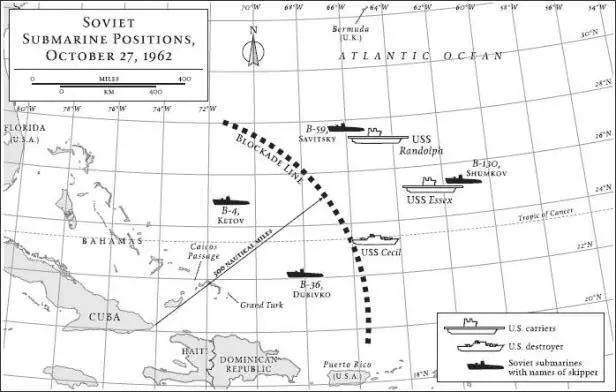

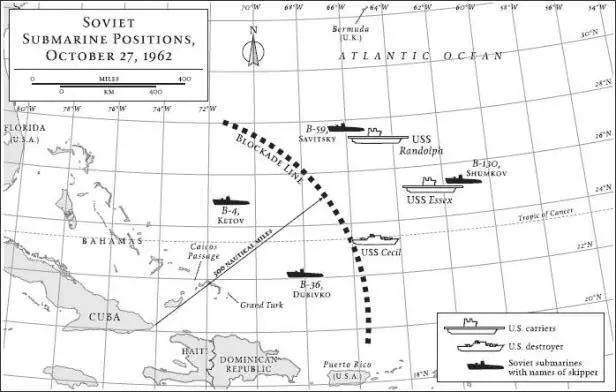

By the afternoon of what was fast becoming Black Saturday, the U.S. Navy had located all four Soviet submarines. They were deployed in a large rectangle, measuring 200 by 400 miles, that stretched in a north-easterly direction from the Bahamas and the Turks and Caicos Islands. It looked as if two of the Soviet submarines had been assigned to protecting Soviet shipping along the northern route to Cuba across the Atlantic, while the other two were deployed along a more southerly route.

The hunt for the Foxtrots took place in secret, unbeknownst to the American public. For the most part, Kennedy permitted the Navy to conduct its antisubmarine operations without much second-guessing. McNamara had warned that it would be “extremely dangerous” to interfere with the decisions of the commander on the scene, or defer an attack on a Soviet submarine that presented a significant threat. “We could easily lose an American ship by that means,” he cautioned the president. The ExComm approved procedures to be used by American ships to signal Soviet submarines to come to the surface. The signals consisted of four or five practice depth charges, to be dropped directly on top of the submarines. Navy chiefs assured McNamara that the depth charges were “harmless.” They were designed to produce a loud explosion beneath the water, but would supposedly cause no material damage to the Soviet vessel.

Hunting Soviet submarines and forcing them to come to the surface was the ultimate game of cat and mouse. Arrayed against the submarines were four hunter-killer carrier groups, each one of which included an aircraft carrier, dozens of planes and helicopters, and seven or eight destroyers. In addition, long-range U.S. Navy P2V anti-submarine aircraft based in Bermuda and Puerto Rico were on constant patrol. The Foxtrots had an entire ocean in which to hide. But at least once a day, they were obliged to come out of their hiding places to communicate with Moscow and recharge their batteries.

Soviet Submarine Positions, October 27, 1962

Earlier in the afternoon, the Americans had photographed a previously unidentified submarine, designated B-4 by the Soviets, 150 miles inside the quarantine line. It submerged immediately after being spotted. B-36, under the command of Captain Dubivko, was moving slowly eastward after being detected in the vicinity of Grand Turk with the help of underwater sonar techniques. A group of hunter-killer destroyers under the aircraft carrier Essex was pursuing the submarine B-130, skippered by Nikolai Shumkov and moving slowly eastward under the power of just one diesel engine.

The most active chase under way on Saturday afternoon was for submarine B-59, known to the Americans as C-19. It was being led by the USS Randolph, a venerable aircraft carrier that had first seen action against Japan in World War II. Helicopters and twin-engined Grumman S2F trackers from the Randolph had been hunting the Soviet sub all day, dropping sonobuoys and triangulating the sound echoes. The search focused on an area three hundred miles south of Bermuda. It was an over-cast day, with the occasional heavy rainstorm.

Читать дальше