Flying this extraordinary airplane required an elite corps of pilots, men who were physically and mentally equipped to roam the upper reaches of earth’s atmosphere at a time when manned space flight was still in its infancy. A U-2 pilot was a cross between an aeronaut and an astronaut. To be selected for the program, he needed to demonstrate a combination of athleticism, intellect, and utter confidence in his own abilities. Training was carried out at “the ranch,” a remote airstrip in the Nevada Desert. Also known as “Area 51,” the ranch was already becoming notorious as the site of numerous alleged UFO sightings, most of which were likely sightings of the U-2. Seen from below, with the sun glinting off its wings, the high-flying spy plane could be mistaken for a Martian spacecraft.

At midnight Alaska time—4:00 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time—Maultsby got the thumbs-up from his mobile control officer. He roared down the runway, pulling the control stick that gave the plane lift. The pogos—sticks with auxiliary wheels that prevented the U-2’s long wings from scraping the ground—dropped away. The flimsy plane soared into the night sky at a steep angle like some exotic black bird.

A U-2 pilot needed to combine two contradictory qualities. To sit strapped into an uncomfortable ejector seat for up to ten hours, he had to transform his body into “a vegetable,” shutting down his normal functions. At the same time, his brain had to operate at full speed. As Richard Heyser, the pilot who discovered the Soviet missiles in Cuba, liked to say: “Your mind never relaxes. If it does, you’re dead.”

Maultsby was about an hour out of Eielson when he flew over the last radio beacon on his way to the North Pole. It was on Barter Island, on the northern coast of Alaska. From now on, he would rely on celestial navigation to keep him on track. The Duck Butt navigators wished him luck and said they would “keep a light on in the window” to guide him back on his return six hours later.

5:00 A.M. SATURDAY, OCTOBER 27 (NOON MOSCOW)

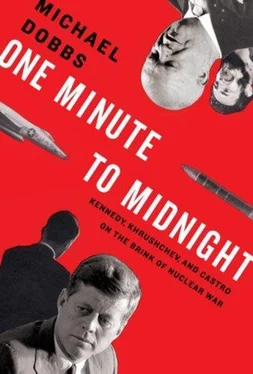

In Moscow, eleven time zones ahead of Alaska, Nikita Khrushchev had just convened another meeting of the Soviet leadership. “They’re not going to invade now,” Khrushchev told the Presidium. Of course, there was “no guarantee.” But an attack on Cuba seemed “unlikely” at a time when the Americans were talking to the United Nations about a possible solution to the crisis. The very fact that Kennedy had responded to proposals by U Thant, the United Nations secretary-general, suggested that he was not about to invade Cuba just yet. Khrushchev was beginning to doubt the president’s “bravery.”

“They had decided to settle matters with Cuba and they wanted to put the blame on us. But now, it seems, they are reconsidering that decision.”

Khrushchev’s mood had changed many times during the course of the week. He seemed to have a different opinion about the likelihood of an American attack on Cuba every time he met with the Presidium members in the wood-paneled conference room down the corridor from his office. News that the Americans had discovered the missiles had filled him with alarm. Kennedy’s decision to go with a blockade rather than an air strike relieved his worst fears. Reports that the Strategic Air Command had declared DEFCON-2—one step short of nuclear war—produced another fit of anxiety. But nothing happened, and he was now feeling a little more relaxed. The immediate pressure was subsiding.

His responses to the crisis reflected his shifting moods, which were in turn shaped by the signals he received from Washington, official and unofficial. His intelligence folder on Friday morning included the distressing news that Kennedy had decided to “finish with Castro” once and for all. The report was based on flimsy evidence: overheard snippets of a conversation at the National Press Club in Washington and a lunch between an American reporter and a Soviet diplomat. But it helped persuade Khrushchev to send his conciliatory-sounding message to Kennedy about untying “the knot of war.”

After another night pondering his options, he believed there was still some time left for negotiation. The Friday message had been vaguely worded, suggesting only that a U.S. noninvasion guarantee would remove “the necessity for the presence of our military specialists in Cuba.” He knew he would probably end up withdrawing the missiles, but he wanted to salvage what he could in retreat. The most obvious concession to demand in return was the withdrawal of American missiles in Turkey.

Khrushchev had good reasons to believe that Kennedy might consider such a compromise. Early on in the crisis, Soviet military intelligence had reported that “Robert Kennedy and his circle” were willing to trade U.S. bases in Turkey and Italy for Soviet bases in Cuba. The information was considered authentic because it came from an agent named Georgi Bolshakov, who had served as a Kremlin backchannel to Bobby Kennedy. More recently, Khrushchev’s interest had been piqued by a syndicated column by Walter Lippmann calling for a Cuba-Turkey missile swap. The Soviets knew the columnist had excellent sources in the Kennedy administration. It seemed unlikely that he was speaking only for himself. Khrushchev understood the Lippmann column as an unattributable feeler from Washington.

“We won’t be able to liquidate the conflict unless we satisfy the Americans and tell them that our R-12 rockets are indeed there,” he told those meeting in the Presidium. “If we can get them to liquidate their bases in Turkey and Pakistan in exchange, then we will have won.”

Other Presidium members expressed approval as Khrushchev dictated the text of another message to Kennedy. As usual, he dominated the meeting with his forceful personality. If the others had concerns about the way he was handling the crisis, they kept their objections to themselves. Unlike his rambling letter of the previous day, Khrushchev’s latest message outlined explicit terms for a deal.

You are worried about Cuba. You say it worries you because it is only ninety miles across the sea from the shores of the United States. However, Turkey is next to us. Our sentinels are pacing up and down and watching each other. Do you believe you have the right to demand security for your country and the removal of weapons that you consider to be offensive, while not recognizing the same right for us?…

This is why I make this proposal: We agree to remove those weapons from Cuba that you categorize as offensive. We agree to state this commitment in the United Nations. Your representatives will make a statement to the effect that the United States, bearing in mind the anxiety and concern of the Soviet state, will evacuate its analogous weapons from Turkey.

Under Khrushchev’s proposal, the United Nations would have responsibility for ensuring implementation of the deal through on-site inspections. The United States would promise not to invade Cuba. The Soviet Union would give a similar pledge to Turkey.

This time, Khrushchev was unwilling to entrust his message to time-consuming diplomatic channels. He wanted to get it to Washington as quickly as possible. He also calculated that publication of a reasonable-sounding proposal would buy him some extra time, since it would put Kennedy on the defensive in the battle for international public relations opinion. The message would be broadcast on Radio Moscow at 5:00 p.m. local time, 10:00 a.m. Saturday morning in Washington.

In the meantime, Khrushchev wanted to make sure a war did not begin by mistake. He had little choice but to approve the measures taken by General Pliyev the previous evening and reported overnight to Moscow, including the activation of air defenses. But he also moved to strengthen Kremlin control over the nuclear warheads. He ordered the return of the R-14 warheads to the Soviet Union aboard the Aleksandrovsk. And he had his defense minister send an urgent cable to Pliyev removing any ambiguity about the chain of command for nuclear weapons:

Читать дальше