On the New York Stock Exchange, trading was hectic, and prices were going up and down like a yo-yo. They had fallen sharply on Tuesday. By Wednesday morning, they were 10 percent down from their summer highs. Gold prices were up. A young economist named Alan Greenspan told The New York Times that “massive uncertainty” would likely result if the crisis continued for any significant length of time.

Fear of nuclear apocalypse was seeping into American popular culture. In Greenwich Village in Manhattan, a tussle-haired bard named Bob Dylan had sat up one night scribbling the words of “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall” on a spiral notepad. He later explained that he wanted to capture “the feeling of nothingness.” Images of apocalypse came tumbling from his brain. Unsure whether he would live to write another song, he “wanted to get the most down I possibly could.”

In another unpublished song, Dylan would describe “the fearful night we thought the world would end” and his fear that World War III could erupt by dawn the next day. He told an interviewer that “people sat around wondering if it was the end, and so did I.”

“Whadda ya have, John?” JFK asked impatiently, as McCone returned to the Cabinet Room.

“The ships are all westbound, all inbound for Cuba,” the CIA director reported. “They either stopped them, or reversed direction.”

“Where did you hear this?”

“From ONI.” The Office of Naval Intelligence. “It’s on its way over to you now.”

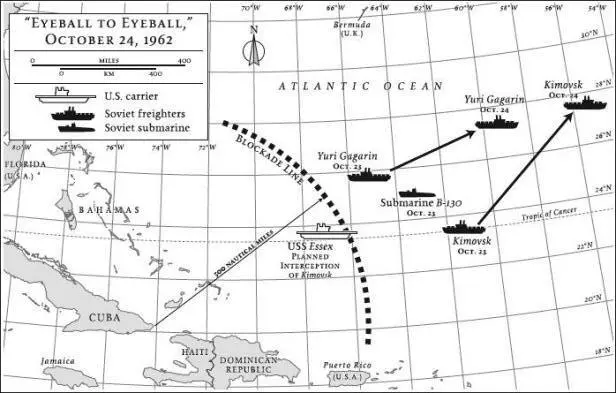

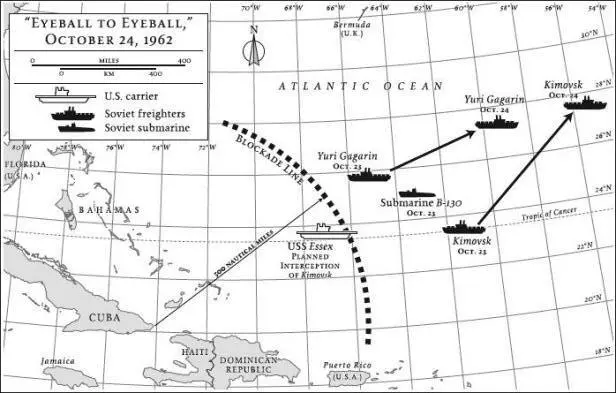

News that the Soviet ships had turned around or were dead in the water came as an enormous relief to the ExComm. After hours of mounting tension, there was a glimmer of hope. An aircraft carrier group led by the Essex had orders to intercept the Kimovsk and her submarine escort. The intercept was scheduled for between 10:30 and 11:00 a.m. Washington time. Believing he had only minutes to spare, Kennedy canceled the intercept.

Dean Rusk suddenly found himself thinking of a childhood game back in Georgia in which boys would stand two feet apart and stare into each other’s eyes. Whoever blinked first lost the game.

“We’re eyeball to eyeball, and the other fellow just blinked,” Rusk told his colleagues.

“The meeting droned on,” Bobby Kennedy would recall later. “But everyone looked like a different person. For a moment the world had stood still, and now it was going around again.”

“SECRET. FROM HIGHEST AUTHORITY,” read the order to the Essex. “DO NOT STOP AND BOARD. KEEP UNDER SURVEILLANCE.”

In fact, it was impossible to do anything of the sort. The Kimovsk was nearly eight hundred miles away from the Essex at the time this order was issued. The Yuri Gagarin was more than five hundred miles away. The “high-interest ships” had both turned back the previous day, shortly after receiving an urgent message from Moscow.

The mistaken notion that the Soviet ships turned around at the last moment in a tense battle of wills between Khrushchev and Kennedy has lingered for decades. The “eyeball to eyeball” imagery served the political interests of the Kennedy brothers, emphasizing their courage and coolness at a decisive moment in history. At first, even the CIA was confused. McCone erroneously believed that the Kimovsk “turned around when confronted by a Navy vessel” during an “attempted” intercept at 10:35 a.m. The news media played up the story of a narrowly averted confrontation on the quarantine line with Soviet ships “dead in the water.” Later on, when intelligence analysts established what really happened, the White House failed to correct the historical record. Bobby Kennedy and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., would describe a standoff on “the edge of the quarantine line” with Soviet and American ships only “a few miles” apart. The myth was fed by popular books and movies like Thirteen Days and supposedly authoritative works like Essence of Decision and One Hell of a Gamble.

Plotting the location of Soviet vessels was an inexact science at best, involving a considerable amount of guesswork. Occasionally, they were sighted by American warships or reconnaissance planes. But usually they were located by a World War II technique known as direction finding. When a ship sent a radio message, it was intercepted by U.S. Navy antennas in different parts of the world, from Maine to Florida to Scotland. The data was then transmitted to a control center near Andrews Air Force Base, south of Washington. By plotting the direction fixes on a map, and seeing where the lines intersected, analysts could locate the source of a radio signal with varying degrees of accuracy. Two fixes were acceptable, three or more ideal.

The Kimovsk had been located 300 miles east of the quarantine line at 3:00 a.m. Tuesday, eight hours after President Kennedy’s television broadcast announcing the blockade. By 10:00 a.m. Wednesday—just over thirty hours later—she was a further 450 miles to the east, clearly on her way home. An intercepted radio message indicated that the ship—whose cargo holds contained half a dozen R-14 missiles—was “en route to the Baltic sea.”

The fixes on other Soviet ships trickled in gradually, so there was no precise “Eureka moment” when the intelligence community determined that Khrushchev had blinked. The naval staff suspected that Soviet vessels were transmitting false radio messages to conceal their true movements. American calculations of Soviet ship positions were sometimes wildly inaccurate because of a false message or a mistaken assumption. Even if the underlying information was correct, direction fixes could be off by up to ninety miles.

Intelligence analysts from different agencies had argued all night over how to interpret the data. It was not until they received multiple confirmations of the turnaround that they felt confident enough to inform the White House. They eventually concluded that at least half a dozen “high-interest” ships had turned back by noon on Tuesday.

ExComm members were disturbed by the lack of real-time information. McNamara, in particular, felt that the Navy should have shared its data hours earlier, even though some of it was ambiguous. He had visited Flag Plot before going to the White House for the ExComm meeting, but intelligence officers had termed the early reports of course changes “inconclusive” and had not bothered to inform him.

“Eyeball to Eyeball,” October 24, 1962

As it turned out, the Navy brass knew little more than the White House. Communications circuits were overloaded and there was a four-hour delay in “emergency” message traffic. The next category down, “operational-immediate traffic,” was backed up five to seven hours. While the Navy had fairly good information about what was happening in Cuban waters, sightings of Soviet ships in the mid-Atlantic were relatively rare. “I’m amazed we don’t get any more from air reconnaissance,” Admiral Anderson grumbled to an aide.

Electronic intelligence was under the control of the National Security Agency (NSA), the secretive code-breaking department in Fort Meade, Maryland, whose initials were sometimes jokingly interpreted to mean “No Such Agency.” That afternoon, NSA received urgent instructions to pipe its data directly into the White House Situation Room. The politicians were determined not to be left in the dark again.

When intelligence analysts finally sorted through the data, it became apparent that the Kimovsk and other missile-carrying ships had all turned around on Tuesday morning, leaving just a few civilian tankers and freighters to continue toward Cuba. The records of the nonconfrontation are now at the National Archives and the John F. Kennedy Library. The myth of the “eyeball to eyeball” moment persisted because previous historians of the missile crisis failed to use these records to plot the actual positions of Soviet ships on the morning of Wednesday, October 24.

Читать дальше