Most bewildered of all were the commanders who had spent the last three months shipping some of the most powerful weapons known to mankind halfway around the world and targeting them on cities like Washington and New York. The commander of the missile troops, Major General Statsenko, found it difficult to understand what Moscow wanted from him. As his men labored to fulfill Khrushchev’s order to dismantle the missile sites, he vented his frustration to a representative of the Soviet General Staff.

“First you urged me to complete the launch sites as quickly as possible. And now you are criticizing me for dismantling them so slowly.”

Over the next few days and nights, Fidel prepared his people for a long struggle ahead. He went back to la colina, the hilltop campus of the University of Havana that had been the scene of his early struggles against Batista, to urge students “to tighten your belts and perhaps even to die” in defense of their homeland. Cuba risked becoming “an abandoned island without oil and electricity,” he warned. “But we prefer to go back to primitive agriculture than accept the loss of sovereignty.”

But even as he fulminated against the Soviets, Castro remained the practical politician. “We won’t make the same mistake twice,” he told his youthful followers. Cuba would not “break with the Russians” so soon after “breaking with the Americans.” Anything was preferable to being driven back into the arms of Uncle Sam. In order to save his revolution, Fidel was willing to make the supreme sacrifice: he would swallow his pride.

Back at the White House, after the rest of the ExComm had left, JFK found himself alone with Bobby. Together, they reviewed the events of the previous thirteen days, and particularly the final day, Black Saturday, when the world had seemed to teeter on the brink of nuclear war. There had been many times over the last twenty-four hours when Kennedy, like Abraham Lincoln before him, had reason to ask himself whether he controlled events or events controlled him.

History, Kennedy understood, does not always flow in predictable directions. Sometimes it can be hijacked by fanatics of various descriptions, by men with long beards, by ideologues living in caves, by assassins with rifles. At others, it can be yanked from its normal path by a combination of chance events, such as an airplane going astray, the misidentification of a missile, or a soldier losing his temper. Statesmen try to bend the chaotic forces of history to their will, with varying degrees of success. The likelihood of an unpredictable event occurring that can change the course of history is always greater at times of war and crisis, when everything is in flux.

The question the world confronted during what came to be known as the Cuban missile crisis was who controlled history: the men in suits, the men with beards, the men in uniform, or nobody at all. In this drama, Kennedy ended up on the same side as his ideological nemesis, Nikita Khrushchev. Neither man wanted war. They both felt an obligation to future generations to rein in the dark, destructive demons they themselves had helped to unleash.

Much of the relief felt by Kennedy on the afternoon of Sunday, October 28, was due to the fact that he and Khrushchev had succeeded in regaining control of historical events. After threatening to erupt in nuclear conflagration, the Cold War would settle back into its familiar rhythm. Men of common sense and reason had defeated the forces of destruction and chaos. The issue now was whether the victory for order and predictability would be long-lasting or fleeting.

Casting around for an appropriate historical precedent, JFK thought of one of his predecessors. On April 14, 1865, five days after accepting the South’s surrender in the Civil War, Lincoln decided to celebrate his moment of triumph by paying a visit to Ford’s Theatre, to see a production of Our American Cousin.

“This is the night I should go to the theater,” said Jack.

Unsure whether to be amused or protective, Bobby played along with his brother’s macabre joke.

“If you go, I want to go with you.”

Some of the characters in this story were quickly forgotten; others were destined for fame and notoriety. Some were disgraced; others rose to positions of great influence. Some led long and happy lives; others had their lives cut short by tragedy. But all were marked in a lasting way by “the most dangerous moment” in history.

The two CIA saboteurs, Miguel Orozco and Pedro Vera, spent seventeen years in Cuban jails before being sent back to the United States. The man who smuggled them into Cuba, Eugenio Rolando Martinez, was arrested at the Watergate Hotel in June 1972 while breaking into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee.

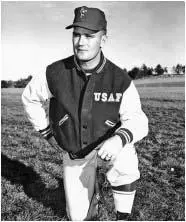

Charles Maultsby was forbidden by the U.S. Air Force from flying anywhere remotely near the North Pole or the Chukot Peninsula. He died of prostate cancer in 1998.

Viktor Mikheev, the Russian soldier killed while preparing a nuclear missile attack on the Guantanamo Naval Base, was buried in Cuban military uniform in Santiago. His remains were later transferred to the Soviet military cemetery in El Chico. His family was told only that he died “performing his internationalist duty.”

George Anderson was dismissed from his position as chief of naval operations in August 1963 and appointed U.S. ambassador to Portugal.

William Harvey was removed as head of Operation Mongoose after the missile crisis and sent as CIA station chief to Rome, where he drank heavily.

Dmitri Yazov became Soviet defense minister in 1987 and led a failed coup against Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev in August 1991.

John Scali served as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations under President Nixon.

Curtis LeMay was caricatured as the maniacal Air Force general Buck Turgidson in Dr. Strangelove. In 1968, he ran for vice president of the United States on a ticket headed by the segregationist George Wallace.

Ernesto “Che” Guevara left Cuba in 1965 to pursue his dream of worldwide revolution. He was killed in the mountains of Bolivia by CIA-supported government forces in 1967.

Robert McNamara remained secretary of defense until 1968. He later repented of his role in escalating the war in Vietnam, and came to believe that only “luck” had prevented nuclear war over Cuba.

Nikita Khrushchev was removed from office in October 1964. His fellow Presidium members accused him of “megalomania,” “adventurism,” “damaging the international prestige of our government,” and taking the world to “the brink of nuclear war.”

Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated in California in June 1968 while campaigning to be elected president.

John F. Kennedy was murdered in November 1963. His assassin had been active in a left-wing protest group that called itself “Fair Play for Cuba.”

Fidel Castro remained in power for another forty-five years. In February 2008, he was succeeded as president of Cuba by his brother, Raul.

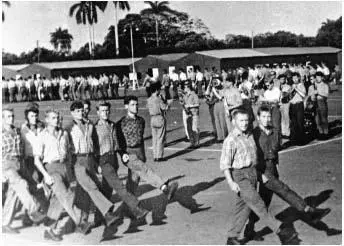

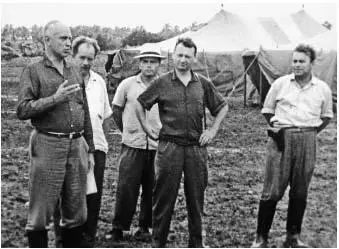

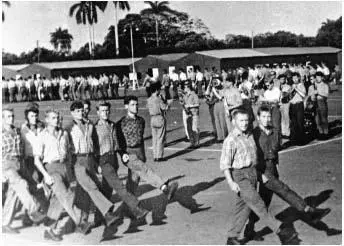

A Soviet motorized rifle regiment stationed near Remedios parades in civilian clothes. Operation Anadyr was nicknamed Operation Checkered Shirt by Russian soldiers because they were issued very similar civilian clothes in hope of disguising their true identities. [ MAVI ]

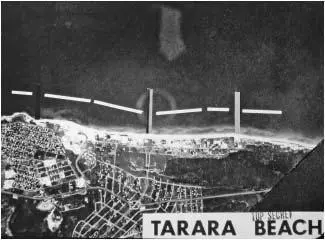

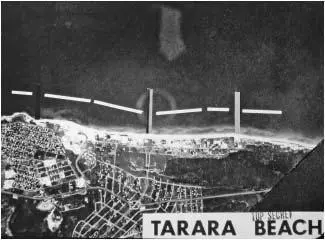

Previously unpublished U.S. Marine reconnaissance photograph of Tarara beach, east of Havana, renamed Red beach in the invasion plan. The Marines were expecting around five hundred casualties during the first day alone, an estimate that assumed the enemy would not use tactical nuclear weapons. [ USNHC ]

Contemporary photograph of Tarara beach. Note the concrete bunker constructed in 1962 against a possible U.S. invasion of Cuba, now used as a lifeguard post for foreign tourists. [ Photo by author ]

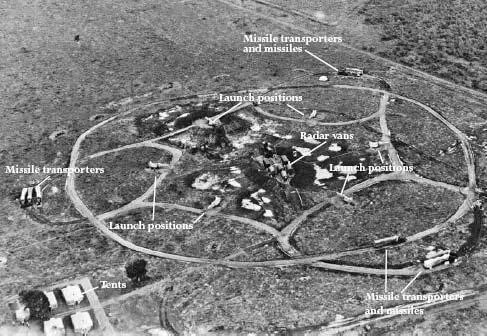

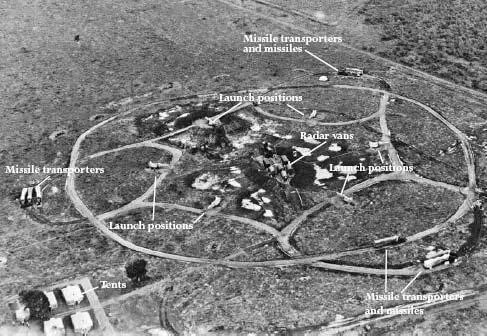

Previously unpublished photograph of the Bejucal nuclear storage site, taken from raw intelligence film shot by U.S. Navy Crusaders on Blue Moon Mission 5008 on October 25. Note the circular road, nuclear warhead vans, single security fence, and lax security at the main gate. See inset of vertical photograph of nuclear warhead vans, shot on the same mission. [ NARA ]

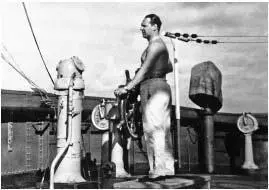

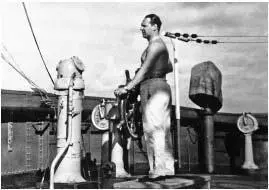

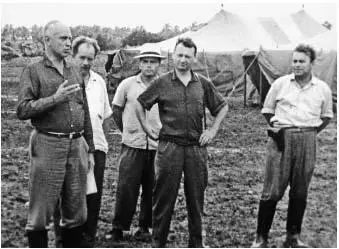

Colonel Nikolai Beloborodov, commander of the Soviet nuclear arsenal on Cuba, at the helm of Indigirka , the first Soviet ship to arrive in Cuba with nuclear warheads. [ MAVI ]

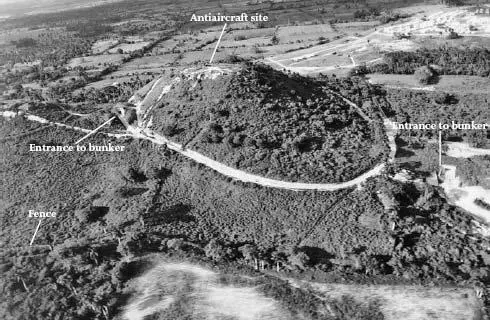

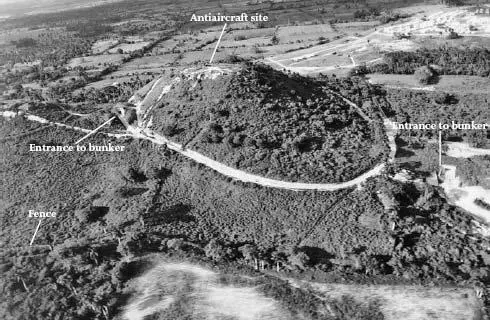

Previously unpublished photograph of the nuclear storage site at Managua, south of Havana, which was used to store the warheads for the tactical FROG/Luna missiles. Labels show the single security fence, the entrances to the bunker, and an antiaircraft site on top of the hill. Photograph shot on October 26 by U.S. Air Force RF-101 on Blue Moon Mission 2623. [ NARA ]

Previously unpublished photographs of raw intelligence film from Blue Moon Mission 5025 on Saturday, October 27, showing frames before and after the pilot detected enemy antiaircraft fire. Frame 47 shows the San Cristobal MRBM Site No. 2. A fraction of a second later, in frame 48, the pilot turns sharply to the left to escape over the mountains. A photograph of a clock embedded in the film (see inset) shows the precise time of the incident, 20:22:34 GMT, which was 16:22:34 Washington time, or 15:22:34 Cuban time. [ NARA ]

The Soviet cruise missile known as FKR, or frontovaya krylataya raketa , was aimed at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base during the Cuban missile crisis. The FKR was an unpiloted version of the MiG-15 jet fighter and could deliver a 14-kiloton nuclear warhead. [ Cuban government photo produced for the 2002 Havana Conference ]

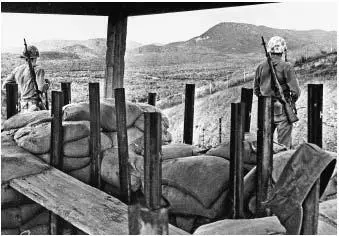

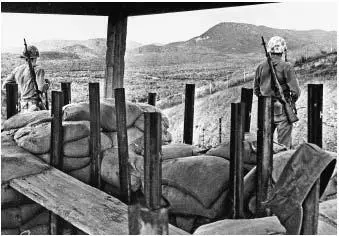

U.S. Marines guarding Guantanamo Bay Naval Base had no idea that nuclear cruise missiles were stationed in hills fifteen miles away. [ Distributed by the Pentagon ]

Photograph of the Banes SAM site, taken by the RF-101 pictured above on October 26. [ NARA ]

Previously unpublished intelligence film of a U.S. Air Force RF-101 overflying the Soviet SAM site at Banes on October 26. The following day, October 27, a U.S. Air Force U-2 piloted by Major Rudolf Anderson was shot down by two missiles fired from this SAM site. Discovered by the author at the National Archives, the consecutive frames were cut and pieced together with Scotch tape by CIA analysts. [ NARA ]

Flying right wing on Blue Moon Mission 2626, this U.S. Air Force RF-101, numbered 41511, took the photograph shown on front page from its left camera bay. [ NARA ]

Colonel Georgi Voronkov (left), commander of the SAM regiment in eastern Cuba, congratulates officers responsible for shooting down Anderson’s U-2. The officer on the right, with a pistol, is Major Ivan Gerchenov, commander of the Banes SAM site. [ MAVI ]

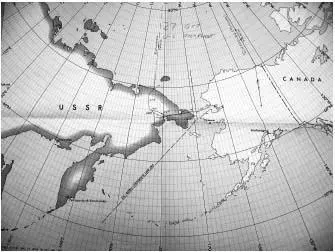

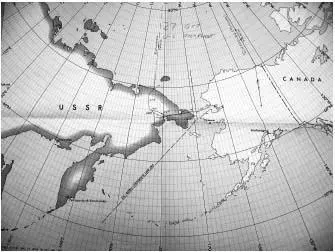

Previously unpublished map of U-2 pilot Captain Charles Maultsby’s overflight of the Soviet Union, found by the author in State Department Archives. [ NARA ]

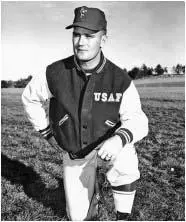

Air Force photo of Captain Maultsby. [ Photo provided by Maultsby family ]

Another U-2 pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson, was shot down over Cuba while Maultsby was in the air over the Soviet Union. [ Photo provided by Anderson family ]

Читать дальше