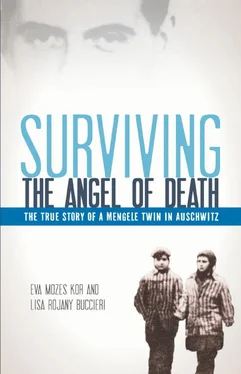

BY EVA MOZES KOR AND LISA ROJANY BUCCIERI

This book is dedicated to the memory of my mother, Jaffa Mozes, my father Alexander Mozes, my sisters Edit and Aliz, and my twin sister, Miriam Mozes Zeiger. I also dedicate this book to the children who survived the camp, and to all the children in the world who have survived neglect and abuse, for I wish to honor their struggle in overcoming the trauma of losing their childhoods, their families, and the feeling that they belong to a family. Last, but not least, this book is dedicated in honor of my son, Alex Kor, and my daughter, Rina Kor, who are my joy, pride, and challenge.

—EMK

To Olivia, Chloe, and Genevieve: the reasons for everything. And to my sister, Amanda, for saving my life.

—LRB

The doors of the train car were thrown all the way open for the first time in many days, the light of day shining upon us like a blessing. Dozens of Jewish people had been crammed into that tiny cattle car as it rattled through the countryside, taking us farther and farther away from our home in Romania. Desperate, people pushed their way out.

I held tightly to my twin sister’s hand as we were shoved onto the platform, not sure whether to be glad for our release or afraid of what was coming. The early morning air was chilly, a cold wind nipping at our bare legs through the thin fabric of our matching burgundy dresses.

I could tell at once that it was very early morning, the sun barely making its way above the horizon. Everywhere I looked there were tall, sharp, barbed-wire fences. High guard towers with SS patrols, Schutzstaffel in German, leaned out, aiming their guns at us. Guard dogs held by other SS soldiers pulled against leashes, barking and growling like a rabid dog I had once seen on the farm, their lips foaming, their teeth flashing white and pointy. I could feel my heart pounding. My sister’s palm clenched sweaty and warm onto my own. My mother and father and our two older sisters, Edit and Aliz, were standing right next to us when I heard my mother’s loud whisper to my father.

“Auschwitz? It’s Auschwitz? What is this place? It’s not Hungary?”

“We are in Germany,” came the reply.

We had crossed over the border into German territory. In actuality, we were in Poland, but the Germans had taken over Poland. Germany’s Poland was where all the concentration camps were. We had not been taken to a Hungarian labor camp to work but to a Nazi concentration camp to die. Before we had time to digest this news, I felt my shoulder being pushed to one side of the platform.

“Schnell! Schnell!” Quick! Quick! SS guards ordered the remaining prisoners from the cattle car out onto the large platform.

Miriam pulled herself closer to me as we were jostled about. The weak daylight was blocked and unblocked as taller people were first jammed up next to us, then pulled away by the guards to one side or the other. It looked like they were choosing some of us prisoners for one thing and some for another. But for what?

That’s when the sounds around us began escalating. The Nazi guards grabbed more people, pulling them to the right or to the left on the selection platform. Dogs were snarling and barking. The people from the cattle car started crying, yelling, screaming all at once; everyone was looking for family members as they were torn away from one another. Men were separated from women, children from parents. The morning erupted into pure pandemonium. Everything started moving faster and faster around us. It was bedlam.

“Zwillinge! Zwillinge!” Twins! Twins! Within seconds, a guard who had been hurrying by stopped short in front of us. He stared at Miriam and me in our matching clothes.

“Are they twins?” he asked Mama.

She hesitated. “Is that good?”

“Yes,” said the guard.

“They are twins,” replied Mama.

Without a word, he grabbed Miriam and me and tore us away from Mama.

“No!”

“Mama! Mama! No!”

Miriam and I screamed and cried, reaching out for our mother, who, in turn, was struggling to follow us with her arms outstretched, a guard holding her back. He threw her roughly to the other side of the platform.

We shrieked. We cried. We pleaded, our voices lost among the chaos and noise and despair. But no matter how much we cried or how loud we screamed, it did not matter. Because of those matching burgundy dresses, because we were identical twins so easily spotted in the crowd of grimy, exhausted Jewish prisoners, Miriam and I had been chosen. Soon we would come face to face with Josef Mengele, the Nazi doctor known as the Angel of Death. It was he who selected those on the platform who were to live and those who would die. But we did not know that yet. All we knew was that we were abruptly alone. We were only ten years old.

And we never saw Papa, Mama, Edit, or Aliz again.

Miriam and I were identical twins, the youngest of four sisters. To hear my older sisters grudgingly tell the story of our birth, you would have known immediately that we two were the darlings of the family. What is sweeter or cuter than identical twin girls?

We were born on January 31, 1934, in the village of Portz in Transylvania, Romania, which is in Eastern Europe near the border of Hungary. From the time we were babies, our mother loved to dress us in the same clothes, putting huge bows in our hair so people would know right away that we little people were twins. She even seated us on the windowsill of our home; passersby thought we were precious dolls, not even real people.

We looked so much alike that she had to put tags on us to tell us apart. Aunts, uncles, and cousins visiting our farm liked to play guessing games with us, trying to divine who was who. “Which one is Miriam? Which one is Eva?” a puzzled uncle would muse with a twinkle in his eye. My mother would smile proudly at her perfect little dolls, and my two older sisters would probably groan. Regardless, most people guessed wrong. When we were older and in school, we would use our identical twinship to trick people, which for us could be so much fun. And we took advantage of how precious and unique we were whenever we could.

Although Papa was strict and admonished us and our mother about the perils of excessive vanity, emphasizing that even the Bible warned against it, Mama particularly cared about our appearance. She had our clothes custom made just for us, like rich people do today with fashion designers. She would order material from the city, and when it arrived, she would take Miriam and me and our two older sisters, Edit and Aliz, to a seamstress in the nearby village of Szeplak. At her house, we girls were permitted to hungrily peruse magazines featuring models wearing the latest styles. But our mother made the final decision on the cut and color of our dresses, for in those days girls always wore dresses, never pants or overalls like boys. And always our mother chose burgundy, powder blue, and pink for Miriam and me. After we were measured, we would set a date for a fitting and when we returned, the seamstress had the dresses ready for us to try on. The styles and colors of the dresses were always identical, two pieces made into one perfect, matching pair.

Other people may have been baffled by our identical twinship, but our father could tell Miriam and me apart by our personalities. By the way I carried my body, a gesture I would make, or the second I opened my mouth to speak, it was clear to him who was who. Although my sister had been born first, I was the leader. I was also outspoken. Any time we needed to ask Papa for something, my oldest sister Edit would encourage me to be the one to approach him.

Читать дальше