Fritz Strassmann, who had always considered Lise Meitner the intellectual leader of their team, refused to accept Hahn’s offer of 1 o percent of his Nobel Prize money made to him alone. He encouraged Lise Meitner to return to Berlin after the war but said he would understand if she refused. They remained friends until her death.

Max Planck was the only German scientist invited to London in 1946 for the belated celebration of the tercentenary of Newton’s birth. He died the following year, having never recovered from the execution of his last surviving son for plotting to assassinate Hitler in 1944.

Of the French atomic scientists, Irene Joliot-Curie died in 1956 of leukemia at the age of fifty-eight. Her husband, Frederic, became high commissioner for atomic energy under Charles de Gaulle but was dismissed for his connections with the French Communist Party and for his opposition to the military uses of nuclear science. He died in 1958, also aged fifty-eight, of cirrhosis of the liver induced, a doctor friend believed, by exposure to polonium.

After the war Paul Tibbets served as a senior officer in the U.S. Air Force, including a tour of duty with NATO in France. He also worked with Boeing on the development of the B-47—the first successful jet bomber. He retired from the air force as a brigadier general to continue what he called his “love affair” with airplanes by running an aviation company. He repeatedly stated that he felt no personal guilt that, as a member of the armed forces, he had planned and carried out the mission assigned to him to the best of his ability. However, in his memoirs he wrote, “Let it be understood that I feel a sense of shame for the whole human race, which through all history has accepted the shedding of human blood as a means of settling disputes between nations.” He added, “Let those who honestly desire peace among nations also condemn all forms of international terrorism that are meant, by their perpetrators, to set the stage for war.” Tibbet’s copilot, Robert Lewis, helped raise money for medical treatment of the so-called Hiroshima maidens—young girls disfigured by the atom blast. In 1971 he sold his “log” of the flight of the Enola Gay at auction for thirty-seven thousand dollars and used some of the money to buy marble to sculpt images with a religious theme. They include a phallic “mushroom statue” symbolically leaking blood. Lewis called it God’s Wind.

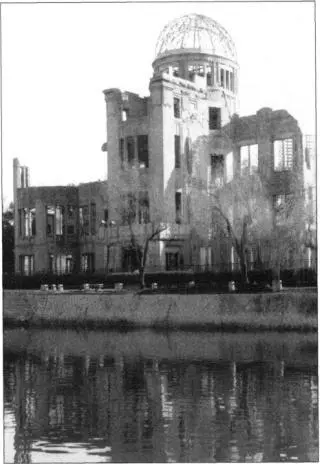

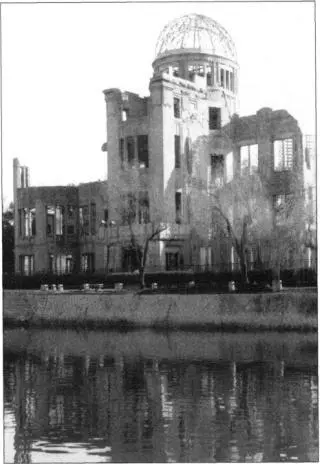

Hiroshima is again a vibrant city with a population more than three times as large as in August 1945, a symbol of the unquenchable human spirit. Citizens bustle to work over the many bridges that link the fingers of land separated by the river delta. Yet Hiroshima remembers. The area beneath the hypocenter of the bomb—the vanished district of Salugakucho—is now the site of the Peace Memorial Park. Memorials, like the bronze Statue of Mother and Child in the Storm, recall the lost people of Hiroshima. Another honors the Korean forced laborers, brought to Hiroshima against their will, who also perished. The dome of the former Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall by the T-shaped Aioi Bridge has simply been left—a shattered icon. Every morning at 8:15 a.m. a bell rings by the dome, and, for just a moment, passersby pause and reflect.

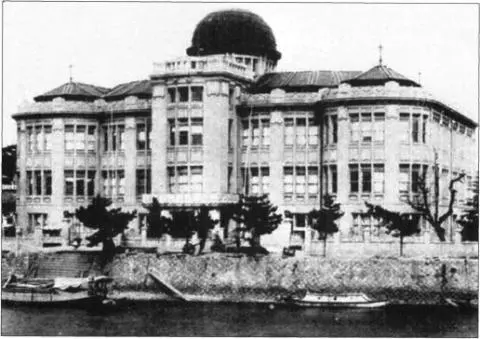

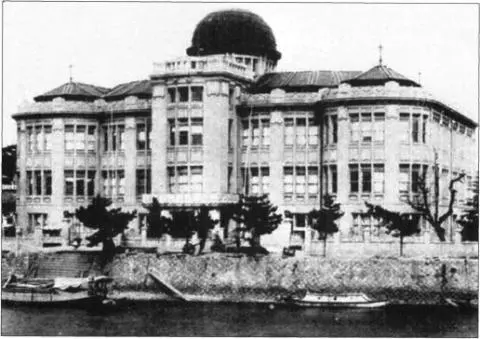

The Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall circa the 1930s

The A-bomb memorial dome as it appears today

QUESTIONS OF “WHAT IF?” litter history. Answers to them can inherently never be certain, and therefore they attract historians like bees to honey. Nevertheless, they provide a useful way of analyzing some of the key facets of the fifty-year story beginning with Marie Curie’s pioneering work on radium and culminating in the destruction of Hiroshima by Little Boy.

The question What if Heisenberg, Bohr, and von Weizsacker had all died in the avalanche of 1933 that buried Heisenberg? leads easily into a discussion of how much a single individual’s input advances the course of science. Shortly after his death Ernest Rutherford’s colleagues debated how much difference it would have made if he had not lived. How much delay would there have been in understanding the nucleus? Some answered, “Ten years,” others answered, “More likely only five.” Even five is probably at the very top end of any realistic scale. Ideas have their time, and if not discovered by one person, they will be by another. Robert Hooke claimed that some of his ideas about natural science predated some of Isaac Newton’s work. Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace worked entirely independently and at the same time on theories of evolution, as did William Swann and Thomas Edison on the lightbulb. Erwin Schrodinger’s wave theory was published within eighteen months of Heisenberg’s quantum mechanics work and was equally illuminating on the movement of atomic particles.

In the early 1930s Ernest Lawrence at Berkeley, not James Chadwick at the Cavendish, could easily have been first to discover the neutron and could also have beaten the Joliot-Curies to “artificial” radioactivity and Fermi to the production of radioactivity using neutrons. Insights into the atom were shared and built on the work of others, as can be seen by the usually high number of references in scientific papers. Good examples of cooperation are Rutherford’s and Bohr’s work on atomic structure and Bohr’s debates with Heisenberg on uncertainty and complementarity. Perhaps a particularly gifted individual can make two or three years’ difference. There are of course exceptions. Einstein’s paper on the special theory of relativity, which “quietly amalgamated space, time and matter into one fundamental unity,” has no references and cites no authorities. How long it would have taken for someone else with his genius to emerge can only be guessed.

What if Britain had not cajoled America to become involved in a bomb project by divulging the secret Maud Report and its trigger—the Frisch-Peierls memorandum—and by sending high-level scientific missions such as that of Henry Tizard with his “black box” of secrets and committed advocates such as Mark Oliphant to the United States? What if Britain had not sent scientists to Los Alamos? Because even a few months’ delay could have meant that the war was ended before Little Boy was ready, this question deserves investigation. The Anglophobic General Groves wrote privately in 1949, “The main British contribution was in arousing and maintaining the interest and enthusiasm of President Roosevelt in the project. This was of real value. Among other things it was probably the major factor in our keeping top priority throughout the war.” One American scientist suggested that the British saved a year in making the bomb. Hans Bethe thought the British contribution to his theoretical team’s work “essential.” Robert Oppenheimer agreed: “I think that the fact that the British were convinced very early by Simon and Peierls probably was the greatest single factor in getting the job done when it was…. If the British Government had not been committed we might have been very much slower in this country to put the necessary resources into it…. The British at Los Alamos were very valuable. If they hadn’t been there it is hard to know who would have taken their place.”

Other historians have, like Groves, emphasized the Frisch-Peierls memorandum, the Maud Report, and Churchill’s constant pressure on Roosevelt to work faster as more important than the British work on the ground. What is clear overall is that, without the British contribution, a bomb would not have been ready until at least very early 1946, after the planned invasion of Japan had gone ahead. It is also true that without Klaus Fuchs’s involvement in the Los Alamos project as part of the British team and his transmission of key secrets to the Russians, the first Soviet test would have been delayed a year or two.

Читать дальше