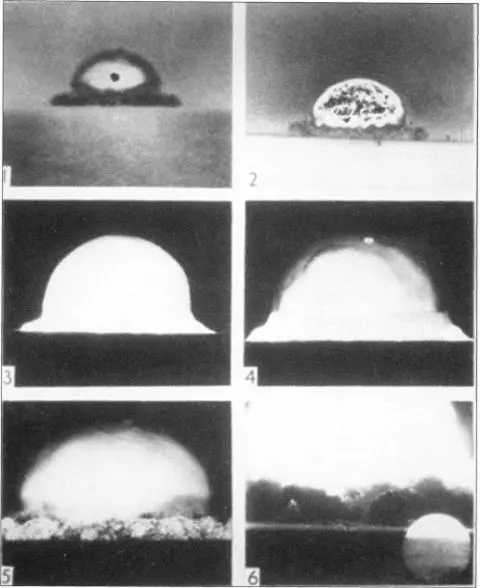

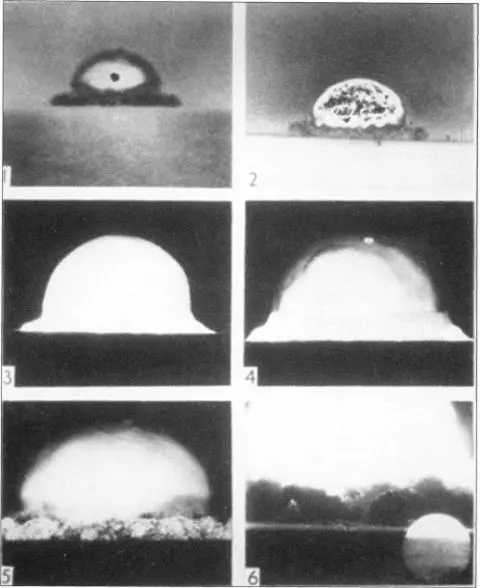

Trinity test bomb

After a few seconds he was able to look at it properly and saw “a pretty perfect red ball, about as big as the sun, and connected to the ground by a short, grey stem. The ball rose slowly, lengthening its stem…. A structure of darker and lighter irregularities became visible, making the ball look somewhat like a raspberry. Then its motion slowed down and it flattened out, but still remained connected to the ground by its stem, looking more than ever like the trunk of an elephant. Then a hump grew out of its top surface and a second mushroom grew out of the top of the first one.” The whole was surrounded by “a purplish blue glow.” Frisch waited, fingers in ears, for the expected blast. The noise, when it reached the man who six years earlier, with his aunt Lise Meitner, had proved the reality of nuclear fission, was in his view “quite respectable.” A long rumbling followed, “not quite like thunder but more regular, like huge noisy wagons running around in the hills.” [38] The emblematic mushroom effect resulted from the thermal updraft created by the explosion and the heat it produced, which sent debris up into the sky, where it flattened out as it reached the stratosphere and the energy dissipated.

To Rudolf Peierls, the explosion had a symbolic as well as a scientific significance: “To us that trial explosion had been the climax…. The brilliant and blinding flash… told us… we had done our job. In that instant… still awed by the indescribable spectacle… we thought more about the work successfully completed than about the consequences.”

Robert Oppenheimer’s first reaction was also a surge of relief, though, as he later told reporters, he was “a little scared of what we had made.” A line from his beloved Bhagavad Gita raced through his brain: “I am become Death, the shatterer of worlds.” To others, though, Oppenheimer’s mood seemed close to euphoria. Rabi recalled, Oppenheimer’s “walk was like [the film] High Noon, I think it’s the best I could describe it—this kind of strut.” General Groves’s reaction was unequivocal satisfaction. During the final seconds he had thought “only of what I would do if, when the countdown got to zero, nothing happened.”

The important question was: How big had the blast been? Enrico Fermi, who to Groves’s irritation had the night before been taking bets on the chances of the explosion igniting the atmosphere, conducted a simple but ingenious experiment. Just after the flash, Groves saw him “dribbling” some torn fragments of paper “from his hand toward the ground. There was no ground wind, so that when the shock wave hit it knocked some of the scraps several feet away.” Fermi measured precisely how far the blast wave had carried them; then, using his slide rule, he calculated the force of the explosion. It was equivalent, he reckoned, to some ten thousand tons of TNT. His improvised “paper chase,” given how much was unknown, was surprisingly accurate; the blast had, in fact, been equivalent to twenty thousand tons of TNT.

Only a few hours after the Trinity test of the plutonium bomb, the heavy cruiser the USS Indianapolis left San Francisco. On board were a gun assembly in a fifteen-foot crate and a lead bucket containing a uranium core—the key components for Little Boy, the uranium-fueled bomb, which the scientists had decided need not be tested before its use in the field.

• • •

The message announcing the success of Trinity reached Stimson at Potsdam in the following terms: “Operated on this morning. Diagnosis not yet complete but results seem satisfactory and already exceed expectations.” Stimson informed Truman and Byrnes. That night Truman wrote in his diary, “I hope for some sort of peace, but I fear that machines are ahead of mortals by some centuries, and when mortals catch up perhaps there’ll be no reason for any of it.”

The next day Stimson passed Churchill a cryptic note, “Babies are satisfactorily born,” which Churchill failed to understand. Stimson then told him explicitly. His diary records Churchill’s subsequent reaction: “‘Now I know what happened to Truman yesterday. I couldn’t understand it. When he got to the meeting after having read this report he was a changed man. He told the Russians just where they got on and off and generally bossed the whole meeting.’ Churchill said he now understood how this pepping up had taken place and that he felt the same way.” According to his own top general, Lord Alanbrooke, Churchill was “completely carried away. It was now no longer necessary for the Russians to come into the Japanese war; the new explosive alone was sufficient to settle the matter. Furthermore we now had something in our hands which would redress the balance with the Russians. The secret of this explosive and the power to use it would completely alter the diplomatic equilibrium which was adrift since the defeat of Germany. Now we had a new value [said Churchill], pushing his chin out and scowling, now we could say if you insist on doing this or that well we can just blot out Moscow, then Stalingrad, then Kiev, Karkhov, Sebastopol etc., etc. Then where are the Russians?” A note from Churchill to his foreign secretary, Anthony Eden, confirmed that his elation and his disdain for Russia were shared by his American counterpart: “It is quite clear that the United States do not at the present time desire Russian participation in the war against Japan.”

With Churchill’s agreement, Truman told Stalin of the bomb. At the end of one day’s meetings he wandered over to Stalin. He later described their conversation: “I casually mentioned to Stalin that we had a new weapon of unusual destructive force. The Russian premier showed no special interest. All he said was that he was glad to hear it and hoped we would make ‘good use of it against the Japanese.’” Their mutual nonchalance concealed not only Truman’s understanding of the bomb’s potential but also Stalin’s prior knowledge of the bomb from Klaus Fuchs’s detailed reports. Stalin was already pressing his generals to hasten their plans for Soviet entry into the war. Nikita Khrushchev later wrote, “Stalin had his doubts about whether the Americans would keep their word…. What if Japan capitulated before we entered the war? The Americans might say, ‘we don’t owe you anything.’”

The Soviets had, immediately prior to the conference, received renewed peace feelers from the Japanese, to which they had given a noncommittal reply. Fortified by their knowledge of the Trinity test, aware of the Japanese peace approaches, and without consulting Stalin, on 26 July Truman, Churchill, and the Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek issued the Potsdam Declaration, offering to Japan what they called “an opportunity to end this war” on the basis of “unconditional surrender.” The declaration ended: “The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.”

Two days earlier, General Marshall and Henry Stimson had approved a directive drafted by General Groves authorizing the atomic bombing of Japan. Although they must have consulted President Truman, his formal consent does not appear in the surviving documents. The first part of the directive to General Carl Spaatz, the newly appointed commander of the Strategic Air Force, reads:

1. The 509 Composite Group, 20th Air Force will deliver its first special bomb as soon as weather will permit visual bombing after about 3 August 1945 on one of the targets: Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata and Nagasaki….

2. Additional bombs will be delivered on the above targets as soon as made ready by the project staff.

Читать дальше