The secret documents outlining the conference’s decisions for the first time also explicitly referred to “war with Britain and the United States” if they continued to block Japanese ambitions and to the desirability of an attack on Russia if Germany destroyed its armies in the West.

Britain and the United States quickly protested the Japanese advance into Indochina, which the Vichy French authorities did not resist. America imposed economic sanctions on Japan, including a freeze on Japanese assets in the United States and an oil embargo. Britain had already placed sanctions on Japan because of its earlier alliance under the Anti-Comintern pact with Britain’s enemies Germany and Italy, but now it also froze Japanese assets. As a consequence of American actions, the emperor ordered the abandonment of any attack on Russia and the creation thereby of a multifront campaign. However, in September 1941, he approved the stepping up of plans for an attack on the United States if diplomatic negotiations failed to secure a sufficiently free hand for Japan in the Far East as well as the removal of the oil embargo. The latter was biting hard and, if not lifted, would cause Japan’s armies to run out of fuel oil within two years.

Negotiations with the United States remained deadlocked, with the Americans insisting on full Japanese withdrawal from China as the price for the removal of sanctions. America also declined the Japanese suggestion of a summit meeting between President Franklin Roosevelt—increasingly preoccupied with support of Britain in the West—and the Japanese prime minister Fumimaro Konoe. War became even more likely when, in mid-October, Emperor Hirohito replaced Konoe with General Hideki Tojo, one of the strongest proponents of war and expansion. On 8 November 1941 the emperor received plans for an attack on Pearl Harbor.

TWELVE

“HE SAID ‘BOMB’ IN NO UNCERTAIN TERMS”

WINSTON CHURCHILL had given the green light to the British atom bomb project at the end of August 1941, but the scale and ambition of the Maud Committee’s recommendations worried many of those involved. Building an atomic bomb could cost millions of pounds, and it seemed doubtful whether Britain, suffering sustained and heavy bombing and short of manpower, could construct the necessarily enormous plants in time to affect the outcome of the war. It needed help, and the obvious place to seek it was across the Atlantic.

News of the Maud Committee’s work had reached the United States quickly, even before Churchill had given the go-ahead. A copy of the draft report was sent to Lynam Briggs as chairman of the Uranium Committee, but he proved unresponsive. In the summer of 1941 Mark Oliphant, a passionate advocate of complete Anglo-American cooperation, was sent to the United States to discover why nothing had been heard from Briggs. He was “amazed and distressed” to discover that Briggs had simply tossed the report into his safe without showing it to the other members of the committee. Perhaps Briggs thought he was being discreet, or perhaps his action—or lack of it—reflected the reality that not a single member of his committee was truly convinced that uranium fission had military potential.

Oliphant attended a meeting of the Uranium Committee to convince them otherwise. Extremely nearsighted and totally deaf in one ear, he was outwardly an unlikely emissary. However, as Samuel Allison of the University of Chicago recalled, “He said ‘bomb’ in no uncertain terms. He told us we must concentrate every effort on the bomb and said we had no right to work on power plants or anything but the bomb. The bomb would cost twenty-five million dollars, he said, and Britain didn’t have the money or the manpower, so it was up to us.” Leo Szilard was so impressed by Oliphant’s passion as he toured key laboratories around the States, cajoling his fellow physicists into action, that he later joked that Congress should create a special medal to recognize “distinguished services” by “meddling foreigners.”

• • •

A few weeks earlier, in July 1941, a draft copy of the Maud Report had, however, also reached Vannevar Bush, the former dean of engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who was then the president of the Carnegie Institution. A man of vigor and vision, in June 1940 he had talked President Roosevelt into appointing him head of the new National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) and had swiftly assumed oversight of the Uranium Committee, whose torpor annoyed him. Roosevelt had subsequently appointed him director of the new Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), reporting directly to the president and responsible for the NDRC. Roosevelt had thus made Bush, in effect, the United States’s science chief. Even so, Bush found it hard to galvanize the Uranium Committee.

Bush’s successor at the NDRC and his overall deputy was James B. Conant, an organic chemist and the president of Harvard. A self-confessed Anglophile, Conant was a modest man with an excellent analytical brain who, during the First World War, had worked on the army’s gas warfare program. Like Bush, he was critical of the piecemeal way in which fission research was being conducted by universities and private and public institutions across the United States.

As a result of his own concerns, Bush had, in April 1941, requested the National Academy of Sciences—America’s scientific elite—to appoint a committee of physicists to review uranium research. However, their two reports, focusing principally on the prospects for generating power from uranium fission, had disappointed him. The creation of violently explosive devices was, they said, a possibility, but too many uncertainties remained for them to make firm recommendations. Some National Academy physicists even thought the whole idea should be “put in wraps” until the war was over.

Ernest Lawrence disagreed. In May 1941 he pointed out that bombs could be made without the complex processes necessary to separate U-235. Unseparated uranium could, he insisted, provide excellent bomb fuel. He reminded the committee of the recent success of two members of his team—Glenn Seaborg and Emilio Segre—in creating, isolating, and analyzing the new element plutonium, which fissioned almost twice as easily as U-235.

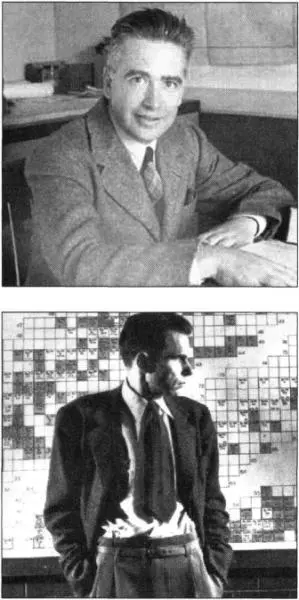

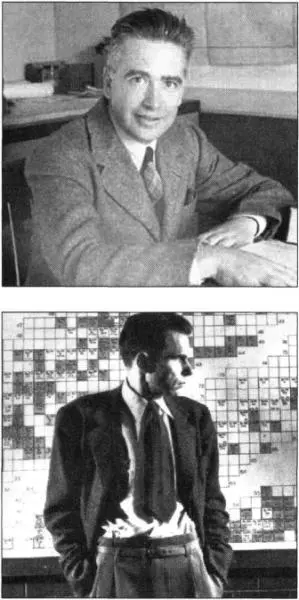

Emilio Segre (top) and Glenn Seaborg

Against this background of cautious inertia in some quarters and passionate advocacy in others, Conant and Bush privately put out feelers to Charles Darwin, the director of the British Central Scientific Office in Washington, a former researcher of Rutherford’s, and grandson of the famous natural scientist. In a letter of 2 August 1941 to the British government, written by hand because of what he called the “extreme secrecy” of its contents, Darwin reported that Conant and Bush had not only raised the issue of atomic bombs but had also proposed a joint U.S.-U.K. atomic bomb program.

Darwin also revealed that he himself had raised a wider issue: Would any government ever deploy such a weapon in reality? “Are,” he wrote, “our Prime Minister and the American President and the respective general staffs willing to sanction the total destruction of Berlin and the country round when, if ever, they are told it could be accomplished at a single blow?” His words echoed both those of Rudolf Peierls and Otto Frisch when they suggested to the British government that the civilian casualties resulting from an atom bomb “may make it unsuitable as a weapon for use by this country” and those of President Roosevelt, who, on the outbreak of war in 1939, had urged belligerents to refrain from “bombardment from the air of civilians or unfortified cities.” However, for many on both sides of the Atlantic, a more pressing issue in 1941 was to determine whether an atomic bomb could actually be built.

Читать дальше