However, the long partnership between Lise Meitner and Otto Hahn was about to end. On 12 March 1938, welcomed by rapturous crowds, German troops marched into Austria and annexed it. Austrian citizenship ceased to exist as the country’s “Aryan” population, hailed by Hitler as German racial comrades, became citizens of the Third Reich. Austria’s Jews became subject to the Reich’s racial laws, enforced by the Austrians with such speed and brutality that even the Germans were startled. Stefan Meyer, Rutherford’s “dear friend,” resigned as director of the Radium Institute in Vienna before he could be dismissed.

The day after Austria’s annexation, a fervent Nazi member of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry, Kurt Hess, denounced Vienna-born Lise Meitner, stating that “the Jewess endangers the institute.” That she had become a Protestant in 1908 was no protection. A friend tipped off Hahn, who hurriedly consulted Heinrich Horlein, the treasurer of an organization that sponsored the institute. Horlein’s view was unambiguous: Lise Meitner must leave. On 20 March, Hahn told Meitner the news, and she wrote in her diary, “Hahn doesn’t want me to come to the institute anymore.” She was “very miserable,” feeling that “he has, basically, thrown me out.” Two days later, Hahn and his wife, Edith, celebrated their silver wedding anniversary. A depressed Meitner was among the guests at what must have been a subdued occasion, with Hahn guiltily aware that “I too had left her in the lurch.” As he later admitted, “I lost my nerve.”

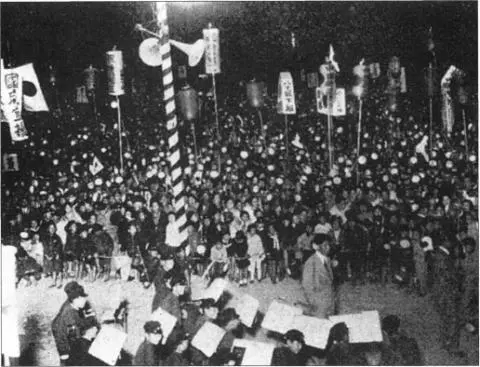

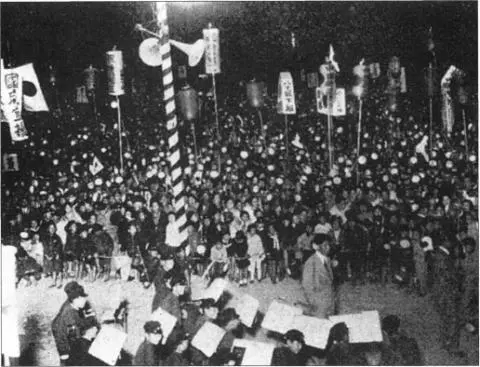

Lantern parade in Hiroshima to celebrate the capture of Nanking by Japanese troops

Lise Meitner turned for help to Paul Rosbaud, a fellow Austrian who was scientific adviser to the German publishing house Springer Verlag and had taken over editorial responsibility for the important scientific journal Naturwissenschaften after its Jewish editor, Arnold Berliner, was fired. Rosbaud had a Jewish wife, whom he took to England with their daughter for safety in 1938. He loathed the Nazis and would later skillfully exploit his contacts across the universities, the military, and industry, as well as within the Nazi Party, as an agent for the British. He would also help many Jews and smuggle food into concentration camps. He took the bewildered and miserable Meitner to visit her lawyer and also to call on several senior members of the hierarchy governing the institute, who, against all the odds, asked her to remain. Horlein, whose first reaction, like Hahn’s, had resulted from panic, had meanwhile changed his mind and was no longer demanding her departure.

Lise Meitner felt paralyzed with indecision. No one had dismissed her, but, she wondered, was it safe or sensible to remain? Friends outside Germany perceived her danger with greater clarity. Several wrote ostensibly inviting her to come and give lectures or seminars but with the underlying purpose of providing her with an official reason to be allowed out of Germany. Among them was Niels Bohr, who asked her to come to Copenhagen, stating that the Danish Physical Society and Chemistry Association would pay her expenses and adding that “you would give my wife and me special pleasure if you would live with us during your stay.” The letter was carefully crafted to convey to the Nazi authorities that Meitner was a scientist of international standing. Experience of helping others get out of Germany had taught Bohr that this tactic sometimes helped. He specified no date but urged her to come quickly.

Still she clung on. The thought of leaving Berlin and her work and all that was familiar was painful to the fifty-nine-year-old spinster. She had until now been shielded from what was happening to Germany’s Jews. Cocooned in the institute, surrounded by friends and colleagues in the scientific community, and until recently an Austrian citizen, she had not been exposed to the full brunt of the Reich’s anti-Jewish policies. The dismissal of Jewish academics in 1933 had been only the start of a much broader campaign to make the lives of Jews intolerable. In 1935 the Nuremberg laws had stripped them of their citizenship. Jews were progressively denied the right to make a living, frozen out of contact with “Aryans,” no longer even allowed to enter public parks. In the first years of their regime the Nazis had encouraged Jewish people to emigrate and allowed them to take money and possessions with them. That was changing. Soon refugees lucky enough to get foreign visas would be allowed to take almost nothing.

Toward the end of April 1938 Meitner learned that the Ministry of Education was considering her position in the institute. Nervously, she tried to find out what was going on while continuing her normal schedule of work. On 23 April she attended Max Planck’s eightieth-birthday celebrations and presented him with a photograph album that was also, perhaps, a farewell gift. Her diary for those weeks shows that, although trying to live an ordinary life, she was coming to accept that her time in Germany was over. She wrote to James Franck, about to leave the Johns Hopkins University for the University of Chicago, seeking his help. He at once lodged an affidavit on her behalf—the first step in the immigration process—and undertook to support her. Yet going to the United States seemed such a huge step. On 9 May she decided instead that she would prefer to join Niels Bohr’s team in Copenhagen. She had admired Bohr since their first meeting in 1920, which she remembered as having “a magic which was only enhanced” on subsequent occasions. Going to Copenhagen also meant she could be with her nephew Otto Frisch.

She was shocked when, next day, officials at the Danish Embassy declared her Austrian passport invalid and refused her a visa. They told her they could act only if she had a German passport. She asked Carl Bosch, the president of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, which administered her institute, to lobby on her behalf. He wrote to the minister of education, asking that “the well-known scientist, Professor Lise Meitner,” be given a German passport and permitted to leave for a neutral country, but days turned into weeks bringing still no news.

In the midst of Lise Meitner’s own anxiety, Otto Hahn’s wife, Edith—her friend since the earliest days of the marriage—had a nervous breakdown, brought on by tension. Then on 14 June came chilling news that, as Meitner wrote in her diary, “technical and academic [people] will not be permitted to leave.” On cue, two days later Bosch received a reply to his letter. His request for a passport for Meitner was refused: “It is considered undesirable that well-known Jews leave Germany to travel abroad where they appear to be representatives of German science.” It concluded, “This statement represents in particular the view of the Reichsfuhrer-SS and Chief of the German Police in the Reichsministry of the Interior”—Heinrich Himmler.

The thought that she had come to Himmler’s personal attention was terrifying. However, the new rules forbidding Jewish scientists to leave were not yet in force, and Lise Meitner’s friends worked frantically. Niels Bohr lobbied scientists in countries with more flexible entry requirements than Denmark’s. He had particular hopes of Holland and launched an appeal to Dutch physicists. Dirk Coster in Groningen, who had been helping Jewish refugees since 1933, and Adriaan Fokker in Haarlem, responded. Both men began trying to raise funds and to find Meitner a job. By late June Coster sent word that he could offer her a position for a year.

Almost simultaneously, Meitner was offered a post at the new Nobel Institute for Experimental Physics in Stockholm, where she would be working under Manne Siegbahn, a scientist she had known for two decades. She decided to go to Sweden if she could. Experimental physics was in its infancy there and would offer her more scope. However, a few days later, a letter from Bohr brought disturbing news. The Swedish offer was not yet firm after all. In particular formalities allowing her to enter Sweden had not been completed. At this worrying moment, she was tipped off by Carl Bosch that the new rules forbidding Jewish scientists to leave were about to come into force. She sent anxious messages to Holland to inquire whether Dirk Coster’s offer was still open. She also wrote to her former assistant, Carl-Friedrich von Weizsacker, asking him to contact his father in the foreign office about her request for a German passport. At just that time, the senior von Weizsacker was overseeing new laws forbidding Jews to transfer any funds out of Germany. Lise was informed that the ministry could not help.

Читать дальше