John Gore - Astronomical Curiosities - Facts and Fallacies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Gore - Astronomical Curiosities - Facts and Fallacies» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Физика, foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Astronomical Curiosities: Facts and Fallacies

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Astronomical Curiosities: Facts and Fallacies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Astronomical Curiosities: Facts and Fallacies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Astronomical Curiosities: Facts and Fallacies — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Astronomical Curiosities: Facts and Fallacies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

With reference to the names given to “craters” on the moon, Prof. W. H. Pickering says, 89 89 Photographic Atlas of the Moon, Annals of Harvard Observatory , vol. li. pp. 14, 15.

“The system of nomenclature is, I think, unfortunate. The names of the chief craters are generally those of men who have done little or nothing for selenography, or even for astronomy, while the men who should be really commemorated are represented in general by small and unimportant craters,” and again —

“A serious objection to the whole system of nomenclature lies in the fact that it has apparently been used by some selenographers, from the earliest times up to the present, as a means of satisfying their spite against some of their contemporaries. Under the guise of pretending to honour them by placing their names in perpetuity upon the moon, they have used their names merely to designate the smallest objects that their telescopes were capable of showing. An interesting illustration of this point is found in the craters of Galileo and Riccioli, which lie close together on the moon. It will be remembered that Galileo was the discoverer of the craters on the moon. Both names were given by Riccioli, and the relative size and importance of the craters [Riccioli large, and Galileo very small] probably indicates to us the relative importance that he assigned to the two men themselves. Other examples might be quoted of craters named in the same spirit after men still living… With the exception of Maedler, one might almost say, the more prominent the selenographer the more insignificant the crater.”

The mathematical treatment of the lunar theory is a problem of great difficulty. The famous mathematician, Euler, described it as incredibile stadium atque indefessus labor . 90 90 Nature , January 18, 1906.

With reference to the “earth-shine” on the moon when in the crescent phase, Humboldt says, “Lambert made the remarkable observation (14th of February, 1774) of a change of the ash-coloured moonlight into an olive-green colour, bordering upon yellow. The moon, which then stood vertically over the Atlantic Ocean, received upon its night side the green terrestrial light, which is reflected towards her when the sky is clear by the forest districts of South America.” 91 91 Humboldt’s Cosmos , vol. iv. p. 481.

Arago said, “Il n’est donc pas impossible, malgré tout ce qu’un pareil résultat exciterait de surprise au premier coup d’œil qu’un jour les météorologistes aillent puiser dans l’aspect de la Lune des notions précieuses sur l’etat moyen de diaphanité de l’atmosphère terrestre, dans les hemisphères qui successivement concurrent à la production de la lumière cendrée.” 92 92 Ibid. , p. 482.

The “earth-shine” on the new moon was successfully photographed in February, 1895, by Prof. Barnard at the Lick Observatory, with a 6-inch Willard portrait lens. He says —

“The earth-lit globe stands out beautifully round, encircled by the slender crescent. All the ‘seas’ are conspicuously visible, as are also the other prominent features, especially the region about Tycho . Aristarchus and Copernicus appear as bright specks, and the light streams from Tycho are very distinct.” 93 93 Monthly Notices , R.A.S., June, 1895.

Kepler found that the moon completely disappeared during the total eclipse of December 9, 1601, and Hevelius observed the same phenomenon during the eclipse of April 25, 1642, when “not a vestige of the moon could be seen.” 94 94 Humboldt’s Cosmos , vol. iv. p. 483 (Otté’s translation).

In the total lunar eclipse of June 10, 1816, the moon during totality was not visible in London, even with a telescope! [95] Humboldt’s Cosmos , vol. iv. p. 483 (Otté’s translation).

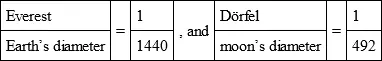

The lunar mountains are relatively much higher than those on the earth. Beer and Mädler found the following heights: Dörfel, 23,174 feet; Newton, 22,141; Casatus, 21,102; Curtius, 20,632; Callippus, 18,946; and Tycho, 18,748 feet. 95 95 Grant, History of Physical Astronomy , p. 229.

Taking the earth’s diameter at 7912 miles, the moon’s diameter, 2163 miles, and the height of Mount Everest as 29,000 feet, I find that

From which it follows that the lunar mountains are proportionately about three times higher than those on the earth.

According to an hypothesis recently advanced by Dr. See, all the satellites of the solar system, including our moon, were “captured” by their primaries. He thinks, therefore, that the “moon came to earth from heavenly space.” 96 96 Popular Astronomy , vol. xvii. No. 6, p. 387 (June-July, 1909).

CHAPTER VI

Mars

Mars was called by the ancients “the vanishing star,” owing to the long periods during which it is practically invisible from the earth. 97 97 Nature , October 7, 1875.

It was also called πυρόεις and Hercules.

I have seen it stated in a book on the “Solar System” by a well-known astronomer that the axis of Mars “is inclined to the plane of the orbit” at an angle of 24° 50′! But this is quite erroneous. The angle given is the angle between the plane of the planet’s equator and the plane of its orbit, which is quite a different thing. This angle, which may be called the obliquity of Mars’ ecliptic, does not differ much from that of the earth. Lowell finds it 23° 13′ from observations in 1907. 98 98 Mars as an Abode of Life (1908), p. 281.

The late Mr. Proctor thought that Mars is “far the reddest star in the heavens; Aldebaran and Antares are pale beside him.” 99 99 Knowledge , May 2, 1886.

But this does not agree with my experience. Antares is to my eye quite as red as Mars. Its name is derived from two Greek words implying “redder than Mars.” The colour of Aldebaran is, I think, quite comparable with that of the “ruddy planet.” In the telescope the colour of Mars is, I believe, more yellow than red, but I have not seen the planet very often in a telescope. Sir John Herschel suggested that the reddish colour of Mars may possibly be due to red rocks, like those of the Old Red Sandstone, and the red soil often associated with such rocks, as I have myself noticed near Torquay and other places in Devonshire.

The ruddy colour of Mars was formerly thought to be due to the great density of its atmosphere. But modern observations seem to show that the planet’s atmosphere is, on the contrary, much rarer than that of the earth. The persistent visibility of the markings on its surface shows that its atmosphere cannot be cloud-laden like ours; and the spectroscope shows that the water vapour present is – although perceptible – less than that of our terrestrial envelope.

The existence of water vapour is clearly shown by photographs of the planet’s spectrum taken by Mr. Slipher at the Lowell Observatory in 1908. These show that the water vapour bands a and near D are stronger in the spectrum of Mars than in that of the moon at the same altitude. 100 100 Nature , March 12, 1908.

The dark markings on Mars were formerly supposed to represent water and the light parts land. But this idea has now been abandoned. Light reflected from a water surface is polarized at certain angles. Prof. W. H. Pickering, in his observations on Mars, finds no trace of polarization in the light reflected from the dark parts of the planet. But under the same conditions he finds that the bluish-black ring surrounding the white polar cap shows a well-marked polarization of light, thus indicating that this dark ring is probably water. 101 101 Bulletin, Ast. Soc. de France , April, 1899.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Astronomical Curiosities: Facts and Fallacies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Astronomical Curiosities: Facts and Fallacies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Astronomical Curiosities: Facts and Fallacies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.