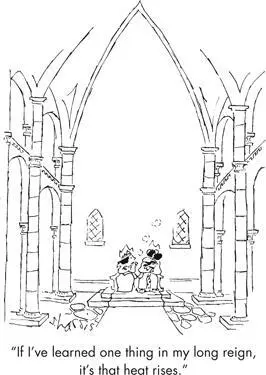

The Greeks’ Christian successors rejected the idea that the universe is governed by indifferent natural law. They also rejected the idea that humans do not hold a privileged place within that universe. And though the medieval period had no single coherent philosophical system, a common theme was that the universe is God’s dollhouse, and religion a far worthier study than the phenomena of nature. Indeed, in 1277 Bishop Tempier of Paris, acting on the instructions of Pope John XXI, published a list of 219 errors or heresies that were to be condemned. Among the heresies was the idea that nature follows laws, because this conflicts with God’s omnipotence. Interestingly, Pope John was killed by the effects of the law of gravity a few months later when the roof of his palace fell in on him.

The modern concept of laws of nature emerged in the seventeenth century. Kepler seems to have been the first scientist to understand the term in the sense of modern science, though as we’ve said, he retained an animistic view of physical objects. Galileo (1564-1642) did not use the term “law” in his most scientific works (though it appears in some translations of those works). Whether or not he used the word, however, Galileo did uncover a great many laws, and advocated the important principles that observation is the basis of science and that the purpose of science is to research the quantitative relationships that exist between physical phenomena. But the person who first explicitly and rigorously formulated the concept of laws of nature as we understand them was René Descartes (1596-1650).

Descartes believed that all physical phenomena must be explained in terms of the collisions of moving masses, which were governed by three laws-precursors of Newton’s famous laws of motion. He asserted that those laws of nature were valid in all places and at all times, and stated explicitly that obedience to these laws does not imply that these moving bodies have minds. Descartes also understood the importance of what we today call “initial conditions.” Those describe the state of a system at the beginning of whatever interval of time over which one seeks to make predictions. With a given set of initial conditions, the laws of nature determine how a system will evolve over time, but without a specific set of initial conditions, the evolution cannot be specified. If, for example, at time zero a pigeon directly overhead lets something go, the path of that falling object is determined by Newton’s laws. But the outcome will be very different depending on whether, at time zero, the pigeon is sitting still on a telephone wire or flying by at 20 miles per hour. In order to apply the laws of physics one must know how a system started off, or at least its state at some definite time. (One can also use the laws to follow a system backward in time.)

With this renewed belief in the existence of laws of nature came new attempts to reconcile those laws with the concept of God. According to Descartes, God could at will alter the truth or falsity of ethical propositions or mathematical theorems, but not nature. He believed that God ordained the laws of nature but had no choice in the laws; rather, he picked them because the laws we experience are the only possible laws. This would seem to impinge on God’s authority, but Descartes got around that by arguing that the laws are unalterable because they are a reflection of God’s own intrinsic nature. If that were true, one might think that God still had the choice of creating a variety of different worlds, each corresponding to a different set of initial conditions, but Descartes also denied this. No matter what the arrangement of matter at the beginning of the universe, he argued, over time a world identical to ours would evolve. Moreover, Descartes felt, once God set the world going, he left it entirely alone.

A similar position (with some exceptions) was adopted by Isaac Newton (1643-1727). Newton was the person who won widespread acceptance of the modern concept of a scientific law with his three laws of motion and his law of gravity, which accounted for the orbits of the earth, moon, and planets, and explained phenomena such as the tides. The handful of equations he created, and the elaborate mathematical framework we have since derived from them, are still taught today, and employed whenever an architect designs a building, an engineer designs a car, or a physicist calculates how to aim a rocket meant to land on Mars. As the poet Alexander Pope said:

Nature and Nature’s laws lay hid in night:

God said, Let Newton be! and all was light.

Today most scientists would say a law of nature is a rule that is based upon an observed regularity and provides predictions that go beyond the immediate situations upon which it is based. For example, we might notice that the sun has risen in the east every morning of our lives, and postulate the law “The sun always rises in the east.” This is a generalization that goes beyond our limited observations of the rising sun and makes testable predictions about the future. On the other hand, a statement such as “The computers in this office are black” is not a law of nature because it relates only to the computers within the office and makes no predictions such as “If my office purchases a new computer, it will be black.”

Our modern understanding of the term “law of nature” is an issue philosophers argue at length, and it is a more subtle question than one may at first think. For example, the philosopher John W. Carroll compared the statement “All gold spheres are less than a mile in diameter” to a statement like “All uranium-235 spheres are less than a mile in diameter.” Our observations of the world tell us that there are no gold spheres larger than a mile wide, and we can be pretty confident there never will be. Still, we have no reason to believe that there couldn’t be one, and so the statement is not considered a law. On the other hand, the statement “All uranium-235 spheres are less than a mile in diameter” could be thought of as a law of nature because, according to what we know about nuclear physics, once a sphere of uranium-235 grew to a diameter greater than about six inches, it would demolish itself in a nuclear explosion. Hence we can be sure that such spheres do not exist. (Nor would it be a good idea to try to make one!) This distinction matters because it illustrates that not all generalizations we observe can be thought of as laws of nature, and that most laws of nature exist as part of a larger, interconnected system of laws.

In modern science laws of nature are usually phrased in mathematics. They can be either exact or approximate, but they must have been observed to hold without exception-if not universally, then at least under a stipulated set of conditions. For example, we now know that Newton’s laws must be modified if objects are moving at velocities near the speed of light. Yet we still consider Newton’s laws to be laws because they hold, at least to a very good approximation, for the conditions of the everyday world, in which the speeds we encounter are far below the speed of light.

If nature is governed by laws, three questions arise:

1. What is the origin of the laws?

2. Are there any exceptions to the laws, i.e., miracles?

3. Is there only one set of possible laws?

These important questions have been addressed in varying ways by scientists, philosophers, and theologians. The answer traditionally given to the first question-the answer of Kepler, Galileo, Descartes, and Newton-was that the laws were the work of God. However, this is no more than a definition of God as the embodiment of the laws of nature. Unless one endows God with some other attributes, such as being the God of the Old Testament, employing God as a response to the first question merely substitutes one mystery for another. So if we involve God in the answer to the first question, the real crunch comes with the second question: Are there miracles, exceptions to the laws?

Читать дальше