Herbert Spencer - The Principles of Biology, Volume 1 (of 2)

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Herbert Spencer - The Principles of Biology, Volume 1 (of 2)» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Философия, foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Principles of Biology, Volume 1 (of 2)

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Principles of Biology, Volume 1 (of 2): краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Principles of Biology, Volume 1 (of 2)»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Principles of Biology, Volume 1 (of 2) — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Principles of Biology, Volume 1 (of 2)», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

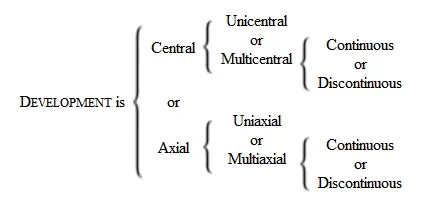

From central development we pass insensibly to that higher kind of development for which axial seems the most appropriate name. A tendency towards this is vaguely manifested almost everywhere. The great majority even of Protophyta and Protozoa have different longitudinal and transverse dimensions – have an obscure if not a distinct axial structure. The originally spheroidal and polyhedral units out of which higher organisms are mainly built, usually pass into shapes that are subordinated to lines rather than to points. And in the higher organisms, considered as wholes, an arrangement of parts in relation to an axis is distinct and nearly universal. We see it in the superior orders of Thallophytes; and in all the cormophytic plants. With few exceptions the Cœlenterata clearly exhibit it; it is traceable, though less conspicuously, throughout the Mollusca ; and the Annelida , Arthropoda , and Vertebrata uniformly show it with perfect definiteness.

This kind of development, like the first kind, is of two orders. The whole germ-product may arrange itself round a single axis, or it may arrange itself round many axes: the structure may be uniaxial or multiaxial . Each division of the organic kingdom furnishes examples of both these orders. In such Fungi as exhibit axial development at all, we commonly see development round a single axis. Some of the Algæ , as the common tangle, show us this arrangement. And of the higher plants, many Monocotyledons and small Dicotyledons are uniaxial. Of animals, the advanced are without exception in this category. There is no known vertebrate in which the whole of the germ-product is not subordinated to a single axis. In the Arthropoda , the like is universal; as it is also in the superior orders of Mollusca . Multiaxial development occurs in most of the plants we are familiar with – every branch of a shrub or tree being an independent axis. But while in the vegetal kingdom multiaxial development prevails among the highest types, in the animal kingdom it prevails only among the lowest types. It is extremely general, if not universal, among the Cœlenterata ; it is characteristic of the Polyzoa ; the compound Ascidians exhibit it; and it is seen, though under another form, in certain of the inferior Annelids.

Development that is axial, like development that is central, may be either continuous or discontinuous: the parts having different axes may continue united, or they may separate. Instances of each alternative are supplied by both plants and animals. Continuous multiaxial development is that which plants usually display, and need not be illustrated further than by reference to every garden. As cases of it in animals may be named all the compound Hydrozoa and Actinozoa ; and such ascidian forms as the Botryllidæ . Of multiaxial development that is discontinuous, a familiar instance among plants exists in the common strawberry. This sends out over the neighbouring surface, long slender shoots, bearing at their extremities buds that presently strike roots and become new individuals; and these by and by lose their connexions with the original axis. Other plants there are that produce certain specialized buds called bulbils, which separating themselves and falling to the ground, grow into independent plants. Among animals the fresh-water polype very clearly shows this mode of development: the young polypes, budding out from its surface, severally arrange their parts around distinct axes, and eventually detaching themselves, lead separate lives, and produce other polypes after the same fashion. By some of the lower Annelida , this multiplication of axes from an original axis, is carried on after a different manner: the string of segments spontaneously divides; and after further growth, division recurs in one or both of the halves. Moreover in the Syllis ramosa , there occurs lateral branching also.

Grouping together its several modes as above delineated, we see that

Any one well acquainted with the facts, may readily raise objections to this arrangement. He may name forms which do not obviously come under any of these heads. He may point to plants that are for a time multicentral but afterwards develop axially. And from lower types of animals he may choose many in which the continuous and discontinuous modes are both displayed. But, as already hinted, an arrangement free from such anomalies must be impossible, if the various kinds of organization have arisen by Evolution. The one above sketched out is to be regarded as a rough grouping of the facts, which helps us to a conception of them in their totality; and, so regarded, it will be of service when we come to treat of Individuality and Reproduction.

§ 51. From these most general external aspects of organic development, let us now turn to its internal and more special aspects. When treating of Evolution as a universal process of things, a rude outline of the course of structural changes in organisms was given ( First Principles , §§ 110, 119, 132). Here it will be proper to describe these changes more fully.

The bud of any common flowering plant in its earliest stage, consists of a small hemispherical or sub-conical projection. While it increases most rapidly at the apex, this presently develops on one side of its base, a smaller projection of like general shape with itself. Here is the rudiment of a leaf, which presently spreads more or less round the base of the central hemisphere or main axis. At the same time that the central hemisphere rises higher, this lateral prominence, also increasing, gives rise to subordinate prominences or lobes. These are the rudiments of stipules, where the leaves are stipulated. Meanwhile, towards the other side of the main axis and somewhat higher up, another lateral prominence arising marks the origin of a second leaf. By the time that the first leaf has produced another pair of lobes, and the second leaf has produced its primary pair, the central hemisphere, still increasing at its apex, exhibits the rudiment of a third leaf. Similarly throughout. While the germ of each succeeding leaf thus arises, the germs of the previous leaves, in the order of their priority, are changing their rude nodulated shapes into flattened-out expansions; which slowly put on those sharp outlines they show when unfolded. Thus from that extremely indefinite figure, a rounded lump, giving off from time to time lateral lumps, which severally becoming symmetrically lobed gradually assume specific and involved forms, we pass little by little to that comparatively complex thing – a leaf-bearing shoot. Internally, a bud undergoes analogous changes; as witness this account: – "The general mass of thin-walled parenchymatous cells which occupies the apical region, and forms the growing point of the shoot, is covered by a single external layer of similar cells, which increase in number by the formation of new walls in one direction only, perpendicular to the surface of the shoot, and thus give rise only to the epidermis or single layer of cells covering the whole surface of the shoot. Meanwhile the general mass below grows as a whole, its constituent cells dividing in all directions. Of the new cells so formed, those removed by these processes of growth and division from the actual apex, begin, at a greater or less distance from it, to show signs of the differentiation which will ultimately lead to the formation of the various tissues enclosed by the epidermis of the shoot. First the pith, then the vascular bundles, and then the cortex of the shoot, begin to take on their special characters." Similarly with secondary structures, as the lateral buds whence leaves arise. In the, at first, unorganized mass of cells constituting the rudimentary leaf, there are formed vascular bundles which eventually become the veins of the leaf; and pari passu with these are formed the other tissues of the leaf. Nor do we fail to find an essentially parallel set of changes, when we trace the histories of the individual cells. While the tissues they compose are separating, the cells are growing step by step more unlike. Some become flat, some polyhedral, some cylindrical, some prismatic, some spindle-shaped. These develop spiral thickenings in their interiors; and those, reticulate thickenings. Here a number of cells unite together to form a tube: and there they become almost solid by the internal deposition of woody or other substance. Through such changes, too numerous and involved to be here detailed, the originally uniform cells go on diverging and rediverging until there are produced various forms that seem to have very little in common.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Principles of Biology, Volume 1 (of 2)»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Principles of Biology, Volume 1 (of 2)» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Principles of Biology, Volume 1 (of 2)» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.