CRAB: What would happen if the caste distribution were entirely random? Would signals still band and disband?

ANTEATER: Certainly. But the colony would not last long, due to the meaninglessness of the caste distribution.

CRAB: Precisely the point I wanted to make. Colonies survive because their caste distribution has meaning, and that meaning is a holistic aspect, invisible on lower levels. You lose explanatory power unless you take that higher level into account.

ANTEATER: I see your side; but I believe you see things too narrowly.

CRAB: How so?

ANTEATER: Ant colonies have been subjected to the rigors of evolution for billions of years. A few mechanisms were selected for, and most were selected against. The end result was a set of mechanisms which make ant colonies work as we have been describing. If you could watch the whole process in a movie—running a billion or so times faster than life, of course—the emergence of various mechanisms would be seen as natural responses to external pressures, just as bubbles in boiling water are natural responses to an external heat source. I don’t suppose you see “meaning” and “purpose” in the bubbles in boiling water—or do you?

CRAB: No, but —

ANTEATER: Now that’s my point. No matter how big a bubble is, it owes its existence to processes on the molecular level, and you can forget about any “higher-level laws.” The same goes for ant colonies and their teams. By looking at things from the vast perspective of evolution, you can drain the whole colony of meaning and purpose. They become superfluous notions.

ACHILLES: Why, then, Dr. Anteater, did you tell me that you talked with Aunt Hillary? It now seems that you would deny that she can talk or think at all.

ANTEATER: I am not being inconsistent, Achilles. You see, I have as much difficulty as anyone else in seeing things on such a grandiose time scale, so I find it much easier to change points of view. When I do so, forgetting about evolution and seeing things in the here and now, the vocabulary of teleology comes back: the meaning of the caste distribution and the purposefulness of signals. This not only happens when I think of ant colonies, but also when I think about my own brain and other brains. However, with some effort I can always remember the other point of view if necessary, and drain all these systems of meaning, too.

CRAB: Evolution certainly works some miracles. You never know the next trick it will pull out of its sleeve. For instance, it wouldn’t surprise me one bit if it were theoretically possible for two or more “signals” to pass through each other, each one unaware that the other one is also a signal; each one treating the other as if it were just part of the background population.

ANTEATER: It is better than theoretically possible; in fact it happens routinely!

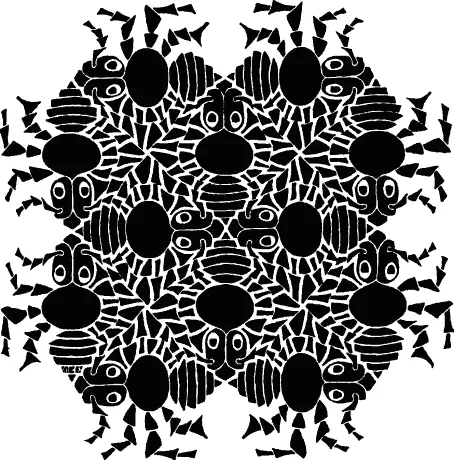

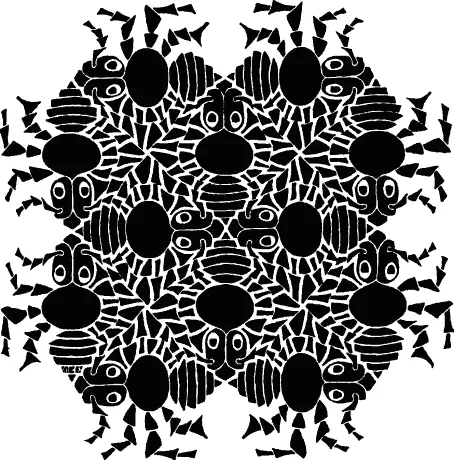

ACHILLES: Hmm.... What a strange image that conjures up in my mind. I can just imagine ants moving in four different directions, some black, some white, criss-crossing, together forming an orderly pattern, almost like—like —

TORTOISE: A fugue, perhaps?

ACHILLES: Yes—that’s it! An ant fugue!

CRAB: An interesting image, Achilles. By the way, all that talk of boiling water made me think of tea. Who would like some more?

ACHILLES: I could do with another cup, Mr. C.

CRAB: Very good.

An “ant fugue” drawn by M. C. Escher (woodcut, 1953.)

ACHILLES: Do you suppose one could separate out the different visual “voices” of such an “ant fugue”? I know how hard it is for me—

TORTOISE: Not for me, thank you.

ACHILLES: —to track a single voice—

ANTEATER: I’d like some too, Mr. Crab —

ACHILLES: —in a musical fugue—

ANTEATER: —if it isn’t too much trouble.

ACHILLES: —when all of them—

CRAB: Not at all. Four cups of tea —

TORTOISE: Three!

ACHILLES: —are going at once.

CRAB: —coming right up!

ANTEATER: That’s an interesting thought, Achilles. But it’s unlikely that anyone could draw such a picture in a convincing way.

ACHILLES: That’s too bad.

TORTOISE: Perhaps you could answer this, Dr. Anteater. Does a signal, from its creation until its dissolution, always consist of the same set of ants?

ANTEATER: As a matter of fact, the individuals in a signal sometimes break off and get replaced by others of the same caste, if there are a few in the area. Most often, signals arrive at their disintegration points with nary an ant in common with their starting lineup.

CRAB: I can see that the signals are constantly affecting the caste distribution throughout the colony, and are doing so in response to the internal needs of the colony—which in turn reflect the external situation which the colony is faced with. Therefore the caste distribution as you said, Dr. Anteater, gets continually updated in a way which, ultimately reflects the outer world.

ACHILLES: But what about those intermediate levels of structure? You were saying that the caste distribution should best be pictured not in terms of ants or signals, but in terms of teams whose members were other teams, whose members were other teams, and so on until; you come down to the ant level. And you said that that was the key to understanding how it was possible to describe the caste distribution as encoding pieces of information about the world.

ANTEATER: Yes, we are coming to all that. I prefer to give teams of a sufficiently high level the name of “symbols.” Mind you, this sense of the word has some significant differences from the usual sense. My “symbols” are active subsystems of a complex system, and they are composed of lower-level active subsystems.... They are therefore quite different from passive symbols, external to the system, such as letters of the alphabet or musical notes, which sit there immobile waiting for an active system to process them.

ACHILLES: Oh, this is rather complicated, isn’t it? I just had no idea that ant colonies had such an abstract structure.

ANTEATER: Yes, it’s quite remarkable. But all these layers of structure are necessary for the storage of the kinds of knowledge which enable an organism to be “intelligent” in any reasonable sense of the word. Any system which has a mastery of language has essentially the same underlying sets of levels.

ACHILLES: Now just a cotton-picking minute. Are you insinuating that my brain consists of, at bottom, just a bunch of ants running around?

ANTEATER: Oh, hardly. You took me a little too literally. The lowest level may be utterly different. Indeed, the brains of anteaters, for instance, are not composed of ants. But when you go up a level or two in a brain, you reach a level whose elements have exact counterparts in other systems of equal intellectual strength—such as ant colonies.

TORTOISE: That is why it would be reasonable to think of mapping your brain, Achilles, onto an ant colony, but not onto the brain of a mere ant.

ACHILLES: I appreciate the compliment. But how would such a mapping be carried out? For instance, what in my brain corresponds to the low-level teams which you call signals?

ANTEATER: Oh, I but dabble in brains, and therefore couldn’t set up the map in its glorious detail. But—and correct me if I’m wrong, Mr. Crab—I would surmise that the brain counterpart to an ant colony’s signal is the firing of a neuron; or perhaps it is a larger-scale event, such as a pattern of neural firings.

CRAB: I would tend to agree. But don’t you think that, for the purposes of our discussion, delineating the exact counterpart is not in itself crucial, desirable though it might be? It seems to me that the main idea is that such a correspondence does exist, even if we don’t know exactly how to define it right now. I would only question one point, Dr. Anteater, which you raised, and that concerns the level at which one can have faith that the correspondence begins. You seemed to think that a signal might have a direct counterpart in a brain; whereas I feel that it is only at the level of your active symbols and above that it is likely that a correspondence must exist.

Читать дальше