But, as John Hawks, an anthropologist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, put it to me, a careful examination of the genetic evidence doesn’t reveal anything as dramatic as a single megavolcanic wipeout. Instead of some Hollywood special-effects extravaganza, human history was more like a perilous immigration story. To understand how immigration can turn a vast population into a tiny one, we need to travel back a few million years to the place and time where we evolved.

Humanity’s first great revolution, according to the anthropologist Ian Tattersall of the American Museum of Natural History, was when it learned to walk upright, more than 5 million years ago. At the time, we were part of a hominin group called Australopithecus that shared a very recent common ancestor with apes. Australopithecines hailed from the temperate, lush East African coast. They were short—about the size of an eight-year-old child—and covered in a light layer of fur. They may have started walking on their hind legs because it helped them hunt and find the fruits that dominated their diets. Whatever the reason, walking upright was unique to Australopithecus . Her fellow primates continued to prefer a four-legged gait, as they do today.

Over the next few million years, Australopithecus walked from the tip of what is now South Africa all the way up to where Chad and Sudan are today. Our ancestors also grew larger skulls, anticipating a trend that has continued throughout human evolution. By about 2 million years ago, Australopithecus was evolving into a very human-looking hominin called Homo ergaster (sometimes called Homo erectus ). Similar in height to humans today, a couple of H. ergaster individuals could put on jeans and T-shirts and blend in fairly well on a typical city street—as long as they wore hats to hide their slightly prominent brows and sloping foreheads. Another thing that would make our H. ergasters feel perfectly comfortable loping down Market Street is the way so many in the crowd around them would be clutching small, hand-sized tools. Our tools may contain microchips whose components are the products of advanced chemical processing, but the typical smartphone’s size and heft are comparable to the carefully crafted hand axes that anthropologists have identified as a key component of H. ergaster ’s tool kit. H. ergaster wouldn’t need anyone to explain the meat slowly cooking over low flames in kebab stands, either: There’s evidence that their species had mastered fire 1.5 million years ago.

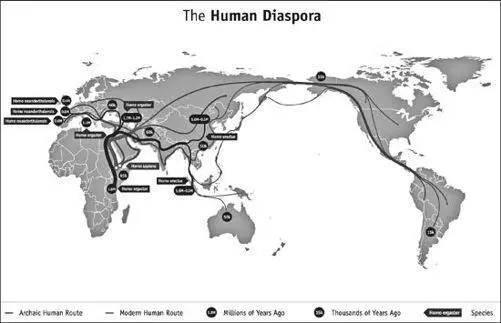

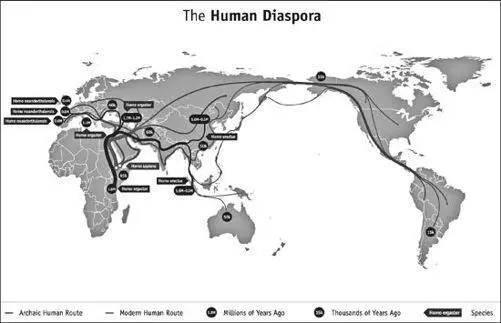

In this map, you can see the different waves of human expansion out of Africa, starting over one million years ago and continuing up into the Homo sapiens diaspora about 100,000 years ago. (illustration credit ill.6)

(Click here to see a larger image.)

There are many ways to tell the story of what happened to H. ergaster and her children, who eventually built those smart phones and invented the tasty perfection that is a kebab. H. ergaster was one of many bipedal, tool-using hominids roaming southern and eastern Africa who had evolved from Australopithecus . The fossil record from this time is fairly sparse, so we can’t be sure how many groups there were, what kinds of relationships they formed with each other, or even (in some cases) which ones evolved into what. But each group had its own unique collection of genes, some of which still survive today in Homo sapiens . And those are the groups whose paths we’re going to follow.

This path is both a physical and a genetic one. A visitor to the American Museum of Natural History in New York can track its progress in fossils. Glass-enclosed panoramas offer glimpses of what we know about how H. ergaster and her progeny created hand axes by striking one stone against another until enough pieces had flaked off that only a sharp blade was left. Reconstructed early human skeletons stand near sparse fossils and tools, a reminder that our ideas about these people come, literally, from mere fragments of their bodies and cultures. Ian Tattersall has spent most of his career poring over those fragments, trying to reconstruct the tangled root structure of humanity’s evolutionary tree.

One thing we know for sure is that early humans were wanderers. Not only did they spread across Africa, but they actually crossed out of it many times, starting about 2 million years ago. Anthropologists can track the journeys taken by H. ergaster and her progeny by tracing the likely paths between what remains of these peoples’ campsites and villages, often identifying the group who lived there based on the kinds of tools they used.

Tattersall believes there were at least three major radiations, or population dispersals, out of Africa. Despite the popularity of Dawkins’s Toba volcano theory, Tattersall believes there was “no environmental reason” for these immigrations. Instead, they were all spurred by evolutionary developments that allowed humans to master their environments. “The first radiation seems to have coincided with a change in body structure,” he mused. Members of H. ergaster had a more modern skeletal structure featuring longer legs than their hominid cohorts, which meant they could walk quickly and efficiently over a variety of terrains. Tattersall explained that there were environmental changes in Africa during this time, but not enough to suggest that humans fled environmental destruction to greener pastures. Instead they were simply well suited to explore “unfamiliar environments, ones very unlike their ancestral environments,” he said. H. ergaster ’s rolling gait was an adaptation that allowed the species to continue adapting, by spreading into new lands where other hominids literally could not tread.

As early humans walked into new regions, they separated into different, smaller bands. Each of these bands continued to evolve in ways that suited the environments where they eventually settled. We’re going to focus on four major players in this evolutionary family drama: our early ancestor H. ergaster and three siblings she spawned— Homo erectus, Homo neanderthalensis, and Homo sapiens .

H. erectus was likely the evolutionary product of that first exodus out of Africa that Tattersall described. About 1.8 million years ago, H. erectus crossed out of Africa through what is today Egypt and spread from there all the way across Asia. These hominins soon found themselves in a very different environment from their siblings back in Africa; the winds were cold and snowy, and the steppes were full of completely unfamiliar wildlife. Over the millennia, H. erectus ’s skull shape changed and so did her tool sets. We can actually track how our ancestors’ tools changed more easily than how their bodies did because stone preserves better than bone. Scientists have reconstructed the spread of H. erectus by unearthing caches of tools whose shapes are quite distinct from what other groups used. From what we can piece together, it seems that H. erectus founded cultures and communities that lasted for hundreds of thousands of years, and spread throughout China and down into Java.

Over the next million years, other groups of humans followed in H. erectus ’s footsteps, walking through Egypt to take their siblings’ route out of Africa. But as the Stanford paleoanthropologist Richard Klein told me, these journeys probably weren’t distinct waves of migration. Walking in small groups, these humans were slowly expanding the boundaries of the hominin neighborhood.

Читать дальше

![Аннали Ньюиц - Автономность [litres]](/books/424681/annali-nyuic-avtonomnost-litres-thumb.webp)