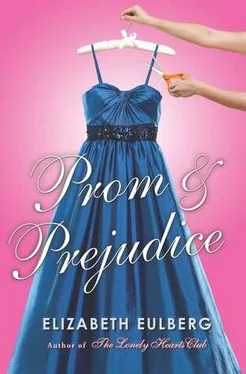

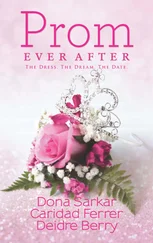

Elizabeth Eulberg

Prom and Prejudice

FOR MY MOTHER,

WHOSE ENTHUSIASM FOR BOOKS IS

CONTAGIOUS,

AND MY FATHER,

WHO INSPIRES ME TO BE A BETTER

PERSON

IT IS A TRUTH UNIVERSALLY ACKNOWLEDGED, THAT A SINGLE girl of high standing at Longbourn Academy must be in want of a prom date.

While the same can probably be said of countless other schools across the country, prom at Longbourn isn't just a rite of passage -- it's considered by many (at least those who matter) to be the social event for future members of high society. Longbourn girls don't go to the mall to get their dresses. No, they boast couture from designers whose names adorn their speed dial.

Just look at the glossy six-page spread dedicated to more than a century of prom history in Longbourn's recruitment brochure. Or the yearly coverage in the New York Times Sunday Style section ... or Vanity Fair ... or Vogue. Fashion reporters and photographers flock to the Connecticut campus to scope out the fashion, the excess, the glamour of it all. It is Fashion Week for the silver spoon set.

The tradition started in 1895, the first year Longbourn opened its doors. Originally set up as a finishing school for proper ladies, the founders realized they needed to have an event to usher their students into the elite world. And while girls nowadays don't really need to be formally "welcomed" into society, nobody wants to give up a weekend-long excuse to dress up and attempt to outshine one another. Friday night is the reception where the couples (consisting of Longbourn girls and, for the most part, boys from the neighboring Pemberley Academy) are introduced. Saturday night is the main event and Sunday afternoon is a brunch where reporters interview the students about the previous evening.

Students become fixated on prom from the day they get accepted. To not attend, or have the proper date, would be a scandal from which a young girl would never be able to recover.

Imagine the chaos that erupted a few years ago, when a scholarship student not only snagged the most sought-after boy at Pemberley, but showed up in a dress from Macy's (the horror!) and caught the eye of the New York Times reporter, who ended up putting her, and her story, on the cover of the Style section.

Up to that point, most students tolerated the two scholarship students in each class. But this was too much.

The following year, hazing began. Most scholarship students couldn't last more than two years. The program only continued because the board of trustees was adamant about diversifying the student body (and by diversify, they meant having students whose parents didn't earn seven-figure yearly bonuses). Plus, the scholarship students, often called "charity cases," helped boost the academic record and music program.

Given the opportunities, education-wise, the scholarship students try to put up with the behavior. After all, this kind of experience couldn't have happened at home. So there was a price to pay for the best teachers, resources, and connections. That price -- condescension, taunts, pranks -- got old pretty quickly.

It's not easy, though. It only took the new scholarship girl in the junior class two days before she broke down in tears. Fortunately, she was alone in her room and nobody saw her. But it happened. I should know. Because that was my room, and my tears. I was a scholarship student. A charity case. One of them.

There was a giant target on my back.

And I had to do everything possible to avoid getting hit.

THE STOMACH PAINS ALWAYS STARTED ONCE THE TRAIN pulled out of Grand Central Station in Manhattan. When I first took the trip, I had butterflies in my stomach, but now I knew better. Now the butterflies had turned to vipers.

Part of me should've been impressed that I'd been able to survive my first semester at Longbourn. I knew I would have difficulties coming in as a junior, but nothing could've prepared me for the cold, wet greeting given to me by several girls on my floor. They thought a proper hello was throwing a milk shake in my face on my way to orientation. I could still feel the cold shock of the strawberry slush hitting my face. I ended up being late to orientation, and when the headmistress asked me for my excuse, I told her I'd gotten lost. I heard snickering throughout the room and wondered how many people had been in on the hazing.

Most of the other things they did to me were subtler: replacing my shampoo with hair removal lotion (luckily, I could smell it before it caused any real damage), tampering with my razor so I got a nasty cut on my leg, putting crushed-up laxatives in my lemonade mix....

I closed my eyes and tried to block out my first week at school. I truly had every intention of coming back from winter break with a positive attitude. I already knew whom to avoid (pretty much everybody except for my roommate, Jane, and the other "charity case" in our class, Charlotte). I was doing well in my classes. I already established myself as the top pianist on campus (which was really important since I was on a music scholarship). And I had a job that I liked because I was able to interact with somewhat normal people (aka "townies"). Oh, and I needed the money. It always seemed to come back to money.

And then there was Ella Gardiner, my piano teacher. She was one of the most prestigious piano instructors in the country, she was on the board of directors at countless music institutions, and she had the reputation of getting her students into the top music programs upon graduation. She was the reason I came to Longbourn, and she was why I had subjected myself to what came along with being a scholarship student.

I grasped on to the scrapbook my friends back home had made me for Christmas. I flipped through the pages of photos, notes, memories from my former life. The life in which I had a tight circle of friends, one that never made me question whether I belonged. I smiled as I looked at the pages filled with photos from the many traditions we started in grade school: Anna's Valentine's Day parties (no boys allowed), our Halloween re-creations of Grease in my living room, holiday gatherings. Then I came to the final section of the scrapbook -- the pages filled with the programs of my various recitals and concerts over the years and photos of my friends gathered around me to celebrate. The very last page had a program from a concert by Claudia Reynolds, the classical pianist that I looked up to, along with a note signed by everybody: To the next Claudia Reynolds, we miss you, but know you're going to accomplish great things. Don't forget us when you're playing Carnegie Hall.

My eyes began to sting with tears. I could never forget my friends, but I had almost forgotten what it was like to have a supportive group of people cheering me on. I closed my eyes and tried to hold on to the memory tightly so it wouldn't slip away.

It was amazing how two weeks away from campus could give you a false sense of security. As the train pulled into the station, I envisioned a force field, like an emotional shield, enveloping my body.

I was smarter, wiser. And I knew better than to let any childish taunts get the best of me. My barrier was up and there was no way I was going to let anybody in.

There was only one person I couldn't wait to see when I got on campus.

"Lizzie!" Jane greeted me as I walked into our room. I'd visited Jane a few times in Manhattan over the break, since I lived right across the Hudson River, in Hoboken, New Jersey. Jane even came to a party one of my friends had back home, and impressed even my most critical friends with her kindheartedness. I knew that someone, somewhere had to be looking out for me to have Jane as my roommate.

Читать дальше