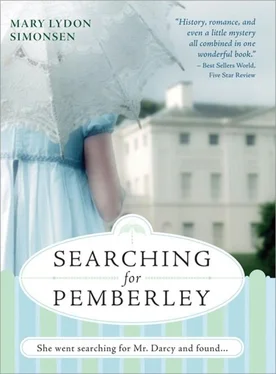

Mary Lydon Simonsen

Searching for Pemberley

To all of my Irish ancestors who made the voyage to America from Galway, Mayo, and Cork, and to all those who have called Minooka, Pennsylvania, home, including my grandmother, Sarah

Sullivan Mahady, and my mother, Hannah Mahady Lydon. You were a hearty breed.

I owe so much to my family who read and reread the manuscript for this work of fiction, including my husband, Paul, my daughters and granddaughter, Meg, Kate, and Kaelyn, my sisters, Betty, Nancy, Kathe, Sally, and Carole. It is a better book because of your suggestions, comments, and encouragement. I couldn’t have done it without you.

For those who have not read Pride and Prejudice or who have not read it recently, please see the Appendix for brief descriptions of the main characters.

Jane Austen’s Characters/Characters from Searching for Pemberley :

Mr. Bennet/John W. Garrison — Father

Mrs. Bennet/Francine Sims Garrison — Mother

Jane Bennet/Jane Garrison Bingham — Oldest Daughter

Elizabeth Bennet/Elizabeth Garrison Lacey — 2nd Daughter

Mary Bennet/Mary Garrison — 3rd Daughter

Kitty Bennet/Celia Garrison Stanton — 4th Daughter

Lydia Bennet/Lucy Garrison Waggoner Edwards — 5th Daughter

George Bingley/George Bingham — Charles’s Eldest Brother

Charles Bingley/Charles Bingham — Jane’s Love Interest

William Collins/Dr. William Chatterton — Charlotte’s Husband

Fitzwilliam Darcy/William Lacey — Elizabeth’s Love Interest

Georgiana Darcy/Georgiana Lacey Oldham — Will Lacey’s sister

Lady Catherine de Bourgh/Lady Sylvia Desmet — Will Lacey’s Aunt

Anne de Bourgh/Anne Desmet — Will Lacey’s Cousin

Col. Fitzwilliam/Col. Alexander Devereaux — Will Lacey’s Cousin

Col. Foster/Col. Fenton — Waggoner’s Colonel

Mr. Gardiner/Mr. Sims — Elizabeth’s Uncle

Mrs. Gardiner/Mrs. Sims — Elizabeth’s Aunt

Charlotte Lucas/Charlotte Ledger Chatterton — Elizabeth’s Friend

George Wickham/George Waggoner — Seducer of Lydia

Longbourn: Bennets End, Hertfordshire

Netherfield Park: Helmsley Hall, Hertfordshire

Pemberley: Montclair, Derbyshire

Rosings Park: Desmet Park, Kent

My hometown is little more than a bump in the road between Scranton and Wilkes-Barre in the hard-coal country of eastern Pennsylvania. At the time of the 1929 stock market crash inaugurating the Great Depression, Minooka had already been in its own depression for five years. The lack of work meant that most of the town’s young people were reading want ads for jobs in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington.

I was in high school in December 1940 when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt gave his famous “Arsenal of Democracy” radio address to the nation. In that speech, the president committed the industrial might of the United States to defeating fascism in Europe. Because of that commitment, factories that had been idled during the Depression were now running three shifts in an attempt to supply Great Britain with the planes, tanks, artillery, and other war materiel needed to defeat Nazi Germany. It seemed as if every company in America was hiring, and the biggest employer of them all was the United States government.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into the war, what had been a steady stream of job seekers to the nation’s capital became a deluge. After graduating from business college in Scranton in June 1944, I headed to Washington to join my two older sisters who had been working in the District since early 1941. Without any experience, I was hired as a clerk typist with the Treasury Department for the princely sum of $1,440 a year. With three paychecks coming in, my sisters and I were able to rent an apartment in a row house near Dupont Circle.

On June 6, 1944, the long-awaited invasion of France had begun, and with the news of the successful landings came the realization that the Allies would win. Finally, on May 8, 1945, America and the world learned that the Germans had officially surrendered. After nearly six years of bloodshed, the war in Europe was over. Now, all resources were being diverted to the Pacific and the defeat of the Empire of Japan.

In August 1945, when the newspapers reported that a B-29 bomber, the “Enola Gay,” had dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, no one understood exactly what an atomic bomb was. Then another was dropped on Nagasaki with casualties reported as being in the tens of thousands from just one bomb. Suddenly, the possibility that the fighting might soon end was very real. On a personal level, this meant I might soon be unemployed.

I need not have worried; my job was never in jeopardy. But with the war over, both of my sisters had decided to return to Minooka, which meant I would have to find a place to live. Although I posted a notice on the bulletin board in the lunchroom advertising for a room or roommate, my heart wasn’t in it. I was ready for a change, and memories of the heat and humidity of a Washington summer provided the motivation. A co-worker mentioned that the Army Exchange Service, the agency responsible for providing goods and services to American service personnel, was hiring for positions in Germany because of the large number of servicemen who were stationed in the American occupation zone. I was not ready to go back home, but if avoiding a return to my hometown meant going to Germany, I didn’t see how that was much of an improvement.

The war in Europe had been over for more than a year, but the newspapers were full of stories and pictures of a defeated Germany with many cities pounded into powder. The aerial bombing and the fighting on the ground had left many of the structures without windows or walls and with their interiors exposed to passersby. Their occupants, often hungry children, looked out at the photographer with faces full of want and despair. I was depressed from reading about it; how would I feel if I actually lived there?

Notwithstanding all the drawbacks, I went on an interview with the Army Exchange Service. Because AES was so short staffed in Germany, the personnel manager told me that if I agreed to a year’s employment in Frankfurt, he would try to get me six months in London. Two weeks later, I sailed for Hamburg and arrived in the former Third Reich in August 1946. As the train pulled into the Frankfurt station, I was met by a scene straight out of Dante’s Inferno . A huge black hulk of twisted metal was all that was left of the once grand railway station. My first inclination was to get the hell out of Dodge, but instead, I took the bus to the Rhein-Main Air Base, my home for the next year.

Although my co-workers insisted that conditions in Frankfurt had improved since that first year after the war’s end, I found it hard to believe when I looked on city block after city block of bombed buildings and piles of rubble or passed Germans on the street who walked with hunched shoulders and downcast eyes. When winter came, it proved to be one of the most brutally cold winters Europe had ever experienced. Rivers were choked with ice, canals froze, rail travel was curtailed, and the coal shortages caused terrible hardships for the Germans. Initially, there was little sympathy for our former enemies, and all contact with the general German population was forbidden. However, by the time I arrived, the non-fraternization policy was a thing of the past, and American servicemen were lining up at military personnel offices to apply for permission to marry German nationals.

After working in Frankfurt for one year, my transfer to London was approved, but because of a reduction in the number of military personnel stationed in Britain, there was no guarantee as to the length of my employment. I was so eager to leave Germany that I agreed and arrived in time to experience late summer in London. Even though the city still showed the extensive damage caused by German bombs, I was more than happy to be in an English-speaking country. I immediately liked England and the English. They were not demonstrative, but in small ways, they showed that they appreciated all the United States had done to help them defeat Germany and Japan.

Читать дальше