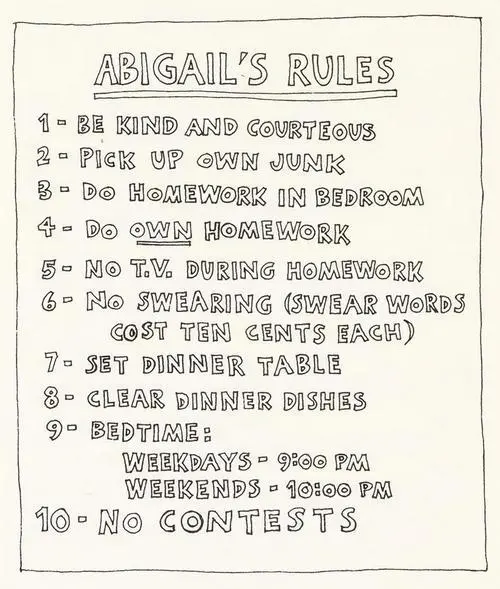

They called me down for breakfast, and the very first thing I saw on the way to the kitchen was the list. I read it silently, and then I went into the kitchen. Mr. Stenner was at the stove, making pancakes. Mr. Stenner considered pancakes quote a family tradition unquote. All he knew how to cook was pancakes. My father could cook sea bass and quiche and all sorts of things. In fact, before the split, one of the few times my parents didn’t argue was when they were planning and cooking a meal together. Mr. Stenner made pancakes every Sunday morning. That’s because he used to make pancakes for his sons every Sunday morning. The one thing he didn’t realize was that his sons really were his family whereas I was not his family. Mom wasn’t either. So the quote family tradition unquote was wasted on us. Or at least on me.

They were playing it cool, both of them. They knew I’d seen the list, knew I’d read it, and were waiting for me to make the first comment. I didn’t disappoint them.

“What do you mean swear words cost ten cents each?” I asked.

“If you swear,” Mr. Stenner said, “we’ll deduct ten cents from your allowance for each...”

“Why?”

“Because it isn’t nice for little girls to use the kind of language you’ve been using,” Mom said.

“Language like what?”

“You know what,” Mr. Stenner said.

“Give me an example of the words I can’t use,” I said.

Mr. Stenner looked me straight in the eye and said, “Shit.”

“Okay,” I said, and shrugged.

“And I think you know the other words,” he said.

“Can I say them now, just to make sure we re both thinking of the same words? I mean, will it cost me a dime if I say them now?”

“Yes.”

“Then how can I be sure...”

“You can be sure we’re both thinking of the same words,” Mr. Stenner said.

“It didn’t cost you anything,” I said. “When you said...”

“Careful,” he said.

“Can I spell it?”

“No.”

“Well, it didn’t cost you anything.”

“When you get to be forty-three years old, you can say whatever you want, too. Meanwhile, it’ll cost you a dime.”

“That isn’t fair.”

“Who says it has to be fair?”

“Huh?”

“Nowhere is it written that grown-ups have to be fair to children,” he said, and flipped a pancake.

“Boy!” I said.

“Right,” he said, and flipped another pancake. He was smiling, the rat.

“And what’s this about doing my own homework? I do do my own homework.”

“Mommy and I do it,” he said.

“You mean because I ask a simple question every now and then?”

“Always.”

“Only every now and then.”

“ Always . There are three things going on every time you do your homework, Abby. The first thing is the television set...”

“I don’t even watch it. I just like to hear the voices. Television helps me concentrate.”

Mr. Stenner rolled his eyes.

“It does.”

“No television,” he said.

“Okay, no damn television.”

“And that’s ten cents,” he said.

“Shit,” I said.

“And that’s another...”

“All right, all right!” I said.

“And no doing your homework in the living room. That’s the second thing that’s going on, all the chatter between Mommy and me, which you re just dying to hear. You’ve got the television on, and you’re listening to our conversation...”

“What’s the third thing?”

“The third thing is constantly asking us what a word means, or how to do an arithmetic problem, or where India is...”

“I know where India is.”

“I think you understand what we’re trying to tell you, Abby,” my mother said.

“All right, I’ll turn off the television, all right? But I’ll do my homework down here.”

“No, you’ll do it upstairs in your bedroom. There’s a desk in your bedroom, that’s what desks are for.”

“I like to spread out.”

“No, you just like to be in the middle of things,” my mother said.

“There’s too much happening down here,” Mr. Stenner said. “You can’t possibly concentrate on what you’re supposed to be doing when...”

“I promise I won’t ask any more questions while I’m doing my homework, okay?”

“No,” Mr. Stenner said.

“Well, why not? If I turn off the television, and I keep quiet...”

“We want some time alone,” Mr. Stenner said.

“What?”

“I said...”

“I heard what you said. You’re alone every night after I go to bed, what do you mean you...”

“When I get home from work,” Mr. Stenner said, “there are lots of things I want to discuss with Mom, most of them private. If you’re sitting here in the living room, with your books sprawled all over the floor...”

“Well, if you’ve got something private to tell her, why don’t you go upstairs, instead of me?”

“Because you’re the poor, put-upon little kid,” Mr. Stenner said, smiling, “and I’m your mean old stepfather.”

“You’re not my stepfather yet, thank God.”

“I will be soon.”

“You know what I’m going to do? I’m going to save all my homework and do it at Daddy’s when I go to see him. Because when I ask him questions, he always...”

“That’s rule number ten,” Mr. Stenner said.

“Huh?”

“No contests,” he said. “Would you like another pancake?”

“No,” I said. “I hate pancakes.”

Two days before the end of January, they left me with a woman named Mrs. Cavallo while they went down to Haiti for Mom’s divorce. They were only gone overnight, but I must’ve called Dad at least a dozen times while they were gone. Mrs. Cavallo didn’t know what was going on. They had told her about the Rules List, and showed her where it was tacked up to the side of the staircase, but I took the list down the minute they drove off, and when Mrs. Cavallo looked for it I told her the wind probably blew it off the wall while the door was open and they were carrying their bags out. Miraculously, the wind blew it back onto the wall, pushpins and all, just before they got home the next day. Mrs. Cavallo told them I’d been a good girl while they were gone, and she also told them I’d spent a lot of time on the telephone with my father.

“You’re not her father?” she asked Mr. Stenner, smiling.

“No,” Mr. Stenner said.

“Ah,” Mrs. Cavallo said, and clucked her tongue. “A second marriage, eh?”

“Yes,” my mother said.

“Ah,” Mrs. Cavallo said again, and counted the money twice when Mr. Stenner paid her for her services.

At dinner that night, Mom told me about Haiti, about how hot it had been down there, and about the beggars on the courthouse steps and on the columned verandah facing a public pump from which a pregnant woman kept drawing water. The woman had made six trips to the pump before Mom was called into the judge’s presence, back and forth over the rock-strewn road, her enormous belly thrust out ahead of her, the laden buckets at the ends of her arms serving almost as counterweights to the unborn child inside her. And then Mom had gone into the courthouse while Mr. Stenner waited outside, and the Miami lawyer representing her had secured the divorce in exactly four minutes. That was how long it had taken. Mom was still amazed that all it had taken was four minutes. Signed, sealed, and delivered — sealed yes. There was a great blob of red sealing wax on the divorce decree, over a pair of flowing red ribbons.

Читать дальше