Evan Hunter - The Paper Dragon

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Evan Hunter - The Paper Dragon» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1967, ISBN: 1967, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: roman, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

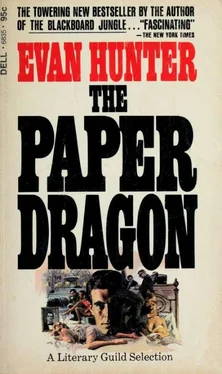

- Название:The Paper Dragon

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1967

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0094530102

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Paper Dragon: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Paper Dragon»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

But as each day passes, the suspense mounts in an emotional crescendo that engulfs them all — and suddenly one man's verdict becomes the most important decision in their lives…

The Paper Dragon — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Paper Dragon», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"So… so you see the ten and the five are the date on that letter, October 5th was when I wrote it, and the man in my husband's book is Peter Malcom who… who made love to me… and… and… and I… the nurse in the book is only me, and the… the lieutenant is my husband, who… who testified in this courtroom yesterday that their love and their future are lost because of a single thoughtless act — isn't that what he said here yesterday? — their love is ruined because of a deception that… that causes a man to get killed. That's… I don't think that's Mr. Constantine's play. I don't think even Mr. Constantine can believe that's his play. My husband's book, you see, is about… about us , you see. That's what his book is about. And… I… I don't think I have anything else to say."

The courtroom was silent.

"Mr. Brackman, do you have any further questions?"

"No questions, your Honor," Brackman said.

Again, there was silence.

"Very well, thank you, Mrs. Driscoll."

Ebie rose, and wiped at her eyes. She looked down when she approached the steps, and then swiftly walked to the jury box. Her husband did not turn toward her as she sat.

"Mr. Brackman," McIntyre said, "I'll allow you to change or add to your summation now if you wish. Or, if you feel you need time for preparation in light of this additional testimony, we can set a date and hear your final argument then."

"I have nothing to add to what I have already said, your Honor."

"Very well. Does anyone have anything further to say?"

"If your Honor please," Willow said, "my opponent has suggested that Mr. Driscoll was attempting to mislead this Court. I have no comment to make on that except that I hope in the light of this subsequent testimony, you will take into consideration the personal elements involved. Thank you, your Honor."

"Anything else, gentlemen?" McIntyre asked. "Very well. I'd like to congratulate you on a good trial and argument. I want you to know that despite whatever moments of levity there were during the trial and in some of our discussions, I nonetheless consider this a most serious matter, and not only because of the large sums of money involved. So it's my intention now to reserve decision on the motions and on the entire case until such time as I can render the opinion a case of such gravity warrants. Thank you, gentlemen. I enjoyed it."

The judge rose.

Everyone in the courtroom rose when he did, and then watched in silence as he came from behind the bench. He walked to the door on his right, nodded briefly as it was opened for him, and then went into his chambers.

The door closed gently behind him.

The courtroom was silent.

There was — Arthur and Driscoll felt it simultaneously and with the same intensity — a sense of incompleteness. They both knew, and had known all along, that there would be no decision on the day the trial ended, and perhaps not for weeks afterward. But whereas this sense of an ending delayed, a final result postponed, was something both men had experienced before and knew intimately, they could not accept it here , not in the context of an apparatus as structured and as well ordered as the law. They sat in pained silence as though willing the judge to reappear, refusing to accept the knowledge that there would be no decision this day, there would be no victor and no vanquished. Instead, there would be only the same interminable wait that accompanied the production of a play or the publication of a book, the same frustrating delay between completion and inalterable exposure.

The judge did not return.

The door to his chambers remained sealed.

The writers stared at the closed door, each slowly yielding to a rising sense of doubt. No matter what Driscoll's wife had been induced to say, Arthur still knew without question that his play had been stolen; and Driscoll knew with equal certainty that he had not stolen it. But what were their respective opinions worth without the corroborating opinion of the judge? In spiraling anxiety, Arthur realized that if the judge decreed his play had not been copied, then the time and energy put into it had been lost, the play was valueless, the play was nothing. And Driscoll similarly realized that if the judge decided against him , then whatever he had said in his novel would mean nothing, he would be stripped of ownership, the book might just as well never have been written.

They each knew despair in that moment, a despair that seemed more real to them than anything they had felt during the course of the trial. In near panic, they wondered what they had left unsaid, what they had forgotten to declare, how they could prove to this impartial judge that there was merit to their work, that they were honest men who had honestly delivered, that they could not be summarily dismissed, nor obliterated by decree.

And then despair led inexorably to reason, and they recognized with sudden clarity that the judge's decision would really change nothing. The truth was there in the record to be appreciated or ignored, but it was there nonetheless, and no one's opinion could ever change it. If there was any satisfaction for them that day, it came with the relief this knowledge brought, a relief that was terribly short-lived because it was followed by the cold understanding that even the trial itself had changed nothing. Whatever paper dragons they had fought in this courtroom, the real dragons still waited for them in the street outside, snarling and clawing and spitting fire, fangs sharpened, breath foul, dragons who would devour if they were not ultimately slain.

The two men sat in silence.

Around them, there was not even a semblance of ceremony or ritual consistent with what had gone before. The attorneys were whispering and laughing among themselves, packing their briefcases, the paid mercenaries taking off their armor and putting away their weapons, and hoping to go home to a hot bowl of soup before hiring on again to fight yet another man's battle on yet another day. Genitori shook hands with Willow, and then Kahn shook hands with Willow, and Sheppard shook hands with both attorneys for API, and then Brackman and his partner walked over to where the defense lawyers stood in a shallow circle and offered his hand first to Willow and then to Genitori, and then introduced all the men to his partner, who beamed in the presence of someone as important as Willow, and then each of the men congratulated each other on how well and nobly the case had been fought, and Brackman said something to Willow off the record, and Willow laughed, and then Genitori told Brackman how wise he was not to have made a second summation, and Brackman in turn complimented Genitori on how expertly he had handled a conceited ass like Ralph Knowles, and they all agreed Knowles had been a very poor witness indeed.

Arthur and Driscoll, apart, watched and said nothing.

Briefcases packed, amenities exchanged, the lawyers again shook hands to show there were no hard feelings between any of them, to assure themselves once again that whatever vile accusations had been hurled in calculated anger within these four walls, they could still express an appreciation of courage and skill, they could still part in the hope that one day they might meet again as battle veterans to reminisce about that terrible week in December when they were fighting a ferocious plagiarism case. And then, because their clients were waiting for the reassuring words that would tide them over through the weeks or perhaps months before the decision came, they moved away from each other cordially and filed out of the courtroom, forming again into two tight, separate groups in the corridor outside, where they talked in low whispers.

They talked only about the trial.

It was easiest to talk about the trial because, for the most part, it had been orderly and serene, moving within the confines of a described pattern toward a conclusion, however delayed. They talked about the trial, and seemed reluctant to leave the corridor, letting several elevators pass them by while they continued to chat, unwilling to make the decisive move that would take them into the next car and then to the street below. Jonah told Genitori and Sheppard that he was positive they had won, positive, and his eyes were glowing even when he sincerely apologized to Driscoll for ever having thought he was guilty. Is that all you have to apologize for? Driscoll asked, and for a moment the corridor went silent, for a moment a pall was cast upon the abounding good fellowship, but only for a moment, only until Jonah grinned and clapped Driscoll on the shoulder and said, Come on, Jimmy, it's all over now, we can all relax. Sheppard grinned too, and chastised himself for having been so stupid, he should have known all along that Mrs. Driscoll was the girl in the book. He saw the pained expression that crossed Driscoll's face, and fell silent. Genitori swiftly said he too was confident they had won, and then speculated aloud on how much the judge would award them for counsel fees.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Paper Dragon»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Paper Dragon» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Paper Dragon» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.