“What’s so funny?” Michael asked.

“Oh, nothing,” Charlotte said breezily, and then turned to the girls again, and again said, “Keep ’em flying, girls,” and went up the steps and into her house. Nor had that been the end of it. Every day since, the girls had given each other the same mysterious farewell, “Keep ’em flying!” They were obviously delighted by our puzzlement, and the harder we pressed them for an explanation, the sillier they became, giggling and exchanging sly glances, and shoving at each other, and generally behaving as though they were carrying around the ultimate secret of the female universe. Up to now, or more accurately up to the minute Linda had let me in on the secret outside the bio lab, I had always thought the slogan was a patriotic reminder to the folks at home, urging them to do their share in the war effort by respecting rationing and the like, and buying war bonds, and keeping silent about troop shipments. But now I knew. And whereas the slogan had a great deal to do with the war effort, it had nothing to do with pilots (although the silk was probably needed for parachutes — that was, in fact, the point) but only to do with the selfless contribution busty Charlotte and her girlfriends were being asked to make in these trying times.

I could hardly wait to let her know I knew.

A single gong sounded into the stillness.

“Okay, kids,” Mr. Hardy said, “drill’s over. You can all go home.”

Outside the school, I looked for Charlotte. I found her just as she was climbing into Dickie Howell’s black Buick and, wouldn’t you know it, I didn’t get a chance to say a word to her.

The house we lived in was the third one we’d owned since I was born, each larger than the one preceding it. It was on a street of similarly old houses, most of them built around the turn of the century, when Chicago’s moneyed landholders were reconstructing after the Great Fire. The street ran from North State to the Drive, and had been surrounded for years by huge modern apartment buildings. It was my guess that the only thing sparing it now was wartime building restrictions. If we won the war — and I couldn’t conceive of our losing it — I was certain that within ten years’ time, East Scott would succumb to the bulldozer as well, and all these lovely old homes would give way to glass and concrete towers.

I loved that old house.

It reminded me, in style though not in grandeur, of what used to be the old Kimball mansion on Prairie and Eighteenth. My father said the Kimball house had been modeled after the Chateau de Josselin in Brittany, and had cost the old piano manufacturer a million dollars to build. Standing on the sidewalk and looking up at it one day, I could well believe it. The house was made entirely of Bedford stone, with turrets and gables everywhere, balconies and stone chimneys, a roof crowned with ornamental ironwork. There were more windows than I could count, flat windows and rounded windows, an oriel window on the north façade. A high fence of iron grillwork surrounded the entire house, and whereas I could have gone in, I suppose (it was then headquarters for the Architects Club of Chicago), I think I was too awed to move from my spot on the sidewalk. My father later told me there were beamed ceilings inside, walls paneled in oak and mahogany, onyx fireplaces in most of the rooms, and even onyx washbowls in the bathrooms, which were tiled from floor to ceiling.

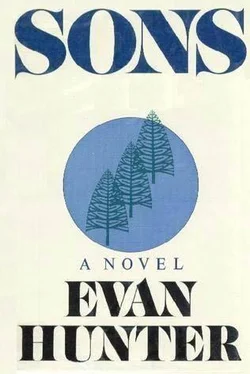

Our house was built in the same French château style, but of course was neither as sumptuous nor as large. The entry hall and dining room were paneled in mahogany, but none of the other rooms were, and there were only three bedrooms in the house, not counting the maid’s room, which was on the ground floor behind the pantry. My father’s library was on the second floor at the top of a winding staircase with a banister Linda and I used to slide down daily. The top panel of our front door was made of frosted glass into which my father had had inserted a sort of Tyler family crest he’d designed, beautifully rendered in stained glass, leaded into the original panel: two green spruce trees towering against a deep blue sky. The doorknob was made of brass, kept highly polished by the succession of colored maids my mother was constantly hiring and firing. (My father said to her one day, “Nancy, you just don’t want another woman living here, now let’s face it.”) From the time I was seven, however, I don’t think we ever went for more than a month without a maid (and sometimes two ) in the house. Whether this was at the insistence of my father or not, I couldn’t say. I did sometimes get the feeling, though, that my mother often longed for the simpler existence she had known in Freshwater, Wisconsin.

She was in the kitchen when I got home that afternoon, but she barely looked up when I came in, being very used to air-raid drills by now. Though, come to think of it, she’d hardly paid any attention to our first air-raid drill, either. That first one had been very exciting to me, because it had come about two weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and half the kids in the school thought the enemy was really over Chicago. The sense of impending disaster was heightened by the fact that the teachers sent us running home, none of that hiding under desks, just run straight home, they told us. So naturally we expected to see a Japanese Zero or two diving on the school, or perhaps a few Bettys unloading their cargo of bombs, it was all very thrilling. Coincidentally, a few Navy Hellcats from the training station winged in over the lake just as we were pouring out of the school, and this nearly started a panic, what with our high expectations for obliteration. I ran all the way home that day, and when I got into the kitchen, out of breath, my mother said, “What is it, Will?”

“The Japs are coming!” I said.

“Don’t be ridiculous,” she said.

“I saw them,” I answered. “Four of them in formation, flying in low over the lake!”

“On earth are no fairies,” my mother said calmly. “You probably saw some planes from the Navy base,” which of course was the truth, but which I wasn’t yet ready to accept. She was standing by the kitchen sink, shelling peas and listening to the radio on the window sill, and her attention never once wandered from her slender hands, a thumbnail slitting each pod, the peas — almost the color of her eyes — tumbling into the colander. The radio was on very loud. My mother was a little hard of hearing in her right ear, and she favored the other car now, her head slightly cocked to the side, as the trials and tribulations of “Just Plain Bill” flooded the kitchen the way they did every afternoon at four-thirty, the indomitable barber desperately trying to turn his lively daughter into a lady, while simultaneously fretting over her stormy marriage to the lawyer Kerry Donovan. I think if the Japanese had really been overhead, my mother would have waited till the end of that day’s installment before running down to the basement. I had never seen her rattled in my life, and she was certainly as calm as glass that day of the first air-raid drill. Honey-blond hair behind her ears, reading glasses perched on top of her tilted head, eyes gazing down at the tumbling peas, she said, “If the Japanese were in Chicago, I’d have heard it on the radio. They’d have interrupted the program. Where’s your sister?”

“On her way home,” I said dejectedly.

I kept watching her in fascination, admiring her calm in the face of certain destruction, yet resenting it as well. She was not a tall woman, five-three or five-four, but whereas I was almost six feet tall, I had the feeling I was looking up at her; it was very unsettling.

“They told us to come straight home,” I said ominously, but my mother went right on shelling peas.

Читать дальше