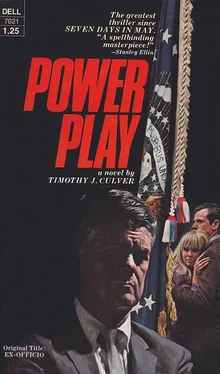

Timothy Culver - Power Play

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Timothy Culver - Power Play» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1971, ISBN: 1971, Издательство: Dell Books, Жанр: roman, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Power Play

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1971

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0440070214

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Power Play: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Power Play»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Occupation: Former President of the United States

Problem: Obsessive desire for power.

Loved and hated more than any man on earth, commanding absolute loyalty from the men and women who once had served him, defying the government he once had headed, Bradford Lockridge pursued his final and possibly insane vision of glory...

Power Play — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Power Play», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“What good does that do us?”

“The nearest bridge is ten miles away at Clark’s Ferry.”

“Okay, we can’t be followed. But we’re on the wrong side of the river. How do we get back to the farm?”

The first said, “We pick up a car on the other side, over in Millersburg. I know how to jump wires. We drive up to Sunbury, come back across the river up there, and come on back south. They’ll be looking for people going the other way, but they won’t be looking for people coming back this way.”

“I like that,” said the third.

“But first we’ve got to get a motorboat,” said the fourth. “How do we do that?”

“To start,” the first told him, “we go to the river.” Being the driver, he now faced front and started the engine, then paused to say, “Any problems?”

There were no problems. He nodded, and the Pontiac moved away from the curb.

South of town there were a number of elderly summer cottages along the river, some with boathouses, locked up now for the winter. In the third of these into which the young men forced their way, they found a motorboat whose engine would start without a key. They flipped coins democratically to decide which one would operate the motorboat, and the other three closed the boathouse doors again after he’d taken the boat out into the river. They stood on shore and waved to him, and he waved back, then turned the prow upstream and went chugging slowly northward. He was in no hurry, and the slow speed was quieter, less likely to draw attention.

The other three returned to the Pontiac, and drove north up route 11/15 to where the campus started on their left. They drove through the south gate, parked in a student parking area, and walked across the campus to the main gate, which faced the president’s house. They all had vague troubled feelings, memories, regrets, as they walked across the campus, which showed as small frowns around their mouths and eyes, but which none of them mentioned to one another.

At the president’s house, a certain amount of overlap was taking place; the undertaker’s men were still carrying equipment out, while the caterer’s men had already started carrying equipment in. The three young men casually crossed the street, walked up to the house, up the stoop to the porch, and through the open front door.

The bustle was limited to a front room on the right. The three moved past that, deeper into the house, eventually finding another area of bustle in the kitchen, where some of the caterer’s men were setting up the coffee urn and the large metal pans of food. There was a rear exit from the kitchen, but it seemed a crowded route to take if in a hurry, so they went looking for an alternate, and eventually found it. Behind the main dining room was a plant-filled solarium, its wall of windows facing the morning sun and the river. French doors led out from here to a stone patio, slate steps led down from there to the lawn.

While two of them waited in the solarium, the third went out and down to the water’s edge, to be sure the one with the motorboat had arrived. He had, and was waiting close to shore, tucked away under a willow that grew on one corner of the property.

When the third man returned to the solarium, he and the other two continued exploring the house, looking now for a place to hide until the funeral party returned. They went up to the second floor, entered several rooms, and in one came unexpectedly face to face with Earl Chatham.

Earl didn’t realize anything was wrong; these looked like clean-cut ordinary young men. He said, “May I help you?”

Thinking that all family members must have gone with the cortege, the leader of the young men decided on boldness as a tactic. He said, “You could tell me what you’re doing up here.”

Earl’s amiable, rather vague face took on the smiling-through-bewilderment expression it often wore when Evelyn more bluntly rejected his advances. He said, “I beg your pardon?”

“No one’s supposed to be up here,” the young man told him firmly. “Are you with the mortician?”

“Of course not,” Earl said. “I’m family.”

The young man was flustered for just a second, but it didn’t show. He said, “Oh, in that case, it’s all right. Come on, men.” And turned around to leave.

Belatedly it occurred to Earl to wonder who these people were and what they wanted. He said, “Just a minute. Who are you three?”

“We’re just keeping an eye on things.” The three trooped on out to the hall.

“Keeping an eye on things?” Earl, following them, frowning now in puzzlement, said, “But I’m supposed to keep an eye on things.”

The leader turned back. “Oh, are you? What’s your assignment?”

“Just a minute, now,” Earl said, with sudden suspicion. “Let me see some identification.”

“Sure,” the leader said, and hit Earl in the mouth.

Earl, staggering backward through the doorway, eyes wide in surprise, managed somehow to stay on his feet. But the three pushed into the room after him and shoved him farther backward, shutting the door behind them. The second time the leader hit Earl, he fell down.

Earl shouted, a call for help from someone who didn’t yet really believe he needed help, and one of the others kicked him in a sudden panic to make him stop. Earl shouted again, this time louder, with more panic in the sound, and all three started kicking him, desperate to keep him silent. He screamed, and the leader grabbed up a table lamp and swung it hard, hitting Earl’s forehead with the metal base. Earl dropped backward flat on the floor, and was silent.

“Good Christ,” one of them said. His voice was hushed.

The leader, trying not to show his shakiness, put the lamp back on the table. “Go see if anybody heard,” he said. Blood was pouring out of Earl’s forehead and down into his hair.

One of the others went to open the door and listen. The third one said, “I think he’s dead.”

“No,” said the leader, “I didn’t hit him that hard.” His nervousness made him irritable.

“Hold a mirror to his mouth,” the second one said.

“He isn’t dead!” the leader said, more angrily than before.

“I don’t feel any pulse,” the third one said. He released Earl’s wrist, and put a hand on Earl’s chest. “I can’t feel him breathing.”

“He’s in shock,” the leader said,

The second one looked around the room, which was Elizabeth’s bedroom. “Where’s a mirror?”

“Never mind that,” the leader said. His voice was unsteady. “We’ve got other things to do.”

“We don’t need a mirror,” the third one said. He wore glasses, which he took off and held so one lens was just above Earl’s mouth.

The leader went over to look out the window, while the second one came back to see if Earl’s breath would fog the glasses. The glasses stayed clear.

The third one put his glasses back on. “He’s dead,” he said.

The leader stayed looking out the window while the other two gazed at his back, waiting for him to do something. Finally, he gave an angry shrug and turned around, saying, “What the hell was he doing here anyway?”

The second one said, “What do we do now?”

“What do we do now? We wait for the funeral party to get back, what do you think?”

“What about this guy?”

“What about him?”

“We can’t just — He’s dead, for Christ’s sake!” Hysteria hung like fog around the edges of his words.

The leader frowned. Fear and nervousness demonstrated themselves in him as irritation.

“Put him in a closet,” he said finally, and turned around again to glare out the window.

The other two looked at one another. After a moment, they picked Earl up and carried him to the closet and put him inside on the floor. His bloody head smeared several of Elizabeth’s dresses.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Power Play»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Power Play» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Power Play» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.