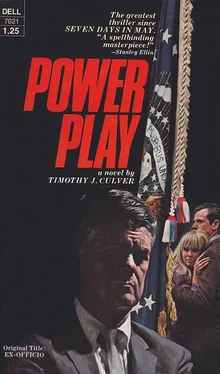

Timothy Culver - Power Play

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Timothy Culver - Power Play» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1971, ISBN: 1971, Издательство: Dell Books, Жанр: roman, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Power Play

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1971

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0440070214

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Power Play: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Power Play»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Occupation: Former President of the United States

Problem: Obsessive desire for power.

Loved and hated more than any man on earth, commanding absolute loyalty from the men and women who once had served him, defying the government he once had headed, Bradford Lockridge pursued his final and possibly insane vision of glory...

Power Play — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Power Play», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“I said,” Elizabeth repeated, “that NATO today is totally useless, simply a drain of resources that could be better used elsewhere. That even by the time of Brad’s term NATO was nothing more than an appendix, not useful for any good purpose but perfectly capable of suddenly turning bad and killing us all.”

What a rotten question! Robert gave her an aggrieved look, his face turned so his host couldn’t see, and then he said, “I don’t think it’s ever been that bad, really. I think it had two values, and probably still does.”

Bradford Lockridge said, “What would those two values be, Robert?”

Robert turned to see that Lockridge was amused behind his stern features. “Well, sir,” he said, “in the first place, NATO coordinated Western military policy, which was certainly a good idea. Each country was going to have its army and air force anyway, so it was safest to have a central control. Otherwise, one nation could have made a bad decision all by itself and dragged the rest of Europe right in after it.”

“Right,” said Lockridge, nodding emphatically. “And what’s the other?”

“Reassurance,” Robert said. He felt a bit nervous, talking global strategy with a man at Bradford Lockridge’s level, but if he just sat there silent all day he’d hate himself tomorrow, and that would be far worse. So he said, “The fact is, there never was a possibility for a Third World War, the atom bomb made that impossible. War at that plateau is suicidal, and national leaders just don’t tend to be suicidal types.”

“Hitler was,” Howard said sourly. Whether he was sour at the thought of Hitler, or at the thought of the time being taken from his galleys was impossible to tell.

Robert nodded. “Yes, you’re right. But you can’t defend against a Hitler, anyway, there just isn’t any defense.”

“One defense,” Bradford said, and waited till they were all looking at him before going on. But it was to Robert that he spoke directly: “A sound global fiscal policy,” he said. “If the Allies hadn’t bled Germany quite so greedily in the twenties, there would have been no Hitler at all. Money makes the mare go. Biafra was a dispute over oil fields, Vietnam a struggle for rubber plantations. Given a sufficiently sound and stable global fiscal policy, which has never yet happened on this Earth, life would become positively dull.” He smiled with one side of his mouth, and said, “Which takes us away from NATO. You said its other value was reassurance, and I’m not quite certain I understand what you mean by that.”

Robert said, “Well, you’ve heard the old saying about military men always getting ready for the war they’ve just finished instead of the one that’ll come next.”

Bradford nodded. “Not necessarily accurate, but frequently.”

“Well, it isn’t just military men,” Robert said, “it’s almost everybody. When the Cold War built up, the people wanted reassurance, and the kind of reassurance they would most easily understand was in terms of the war that had just been won. That’s why there was so much interest in fallout shelters in the fifties. If the bombs did fall, they would destroy everything for fifty miles around and fill the air with lethal radiation for seven years, and everybody knew that, but what did they do? They pretended the problem was simply a bigger version of the London blitz, because that they could contend with. They could dig bomb shelters and change the term for them.”

Bradford frowned. “You’re saying that NATO is of the same order?”

Robert felt a chill of uncertainty, with the older man’s eyes on him. He was merely a theoretician himself, but Bradford Lockridge had been there. Still, there was nothing to do at this point but go forward, so he said, “That’s the way it seems to me. NATO is a carefully planned and brilliant defense against Hitler and the German army of the early forties. Since if there were a Russian attack against the West it would bypass Europe entirely and strike first at the United States, NATO has never been anything but a beautiful window display to reassure the folks back home; to let them know if the Second World War ever comes back, we’re ready for it.”

Bradford smiled, but he said, “Is that merely a funny joke, or do you mean it?”

“I mean it,” Robert said. “At the beginning of the Cold War, the government knew it had to reassure the people that they were safe, so they—” But at that point he suddenly became aware again of who he was talking to, and faltered. “That is, the way it worked out—”

“That’s all right,” Bradford said gently. “That was before my administration.”

Robert gave him a grateful smile and said, “Thank you, sir. The point was, there was no defense against the Third World War, but the people were going to lose confidence in a government that didn’t promise to defend them, so what they were given was a perfectly adequate defense against the war we’d just won. The whole object of NATO, besides coordinating European military policy, was to give people the comfortable feeling that something was being done.”

Mrs. Canby, who until now hadn’t said a word throughout the meal, suddenly said, “Isn’t that awfully cynical, Mr. Pratt? The people I’ve met in government have tended to be more honest than that.”

Robert turned to her, both in surprise at hearing her speak up and in relief at the opportunity to get out from under Bradford Lockridge’s scrutiny for a few seconds. “I hope it isn’t cynical,” he said. “I don’t really believe that someone sat down in the White House or somewhere and cynically worked out this whole complex global con game to delude the masses. I believe the people generally were scared and worried, and their attitude communicated itself to the decision-makers—”

Bradford interposed, “Who were possibly themselves also scared and worried.”

“Of course,” Robert said, turning back to him for an instant. “People in government I’m sure have the same doubts and the same need for reassurance as people outside. More, even, because they know more about the near misses.” He turned back to Mrs. Canby, saying, “The people in charge did the best they could, but the problem was insoluble because there really isn’t any defense against the kind of weapons that now exist.” He turned to Bradford again, saying, “We aren’t too far from Pittsburgh, are we, sir?”

“About a hundred miles,” Bradford said. “Perhaps a little more.”

“Thank you.” To Mrs. Canby again he said, “Pittsburgh would be a prime target if an all-out war started. Hit Pittsburgh with one of today’s bombs, and everybody in this house would die, and no one would be able to live in this neighborhood for the next seven years.”

Howard said, “There are clean bombs.”

Robert said, “If someone were anxious enough to destroy the United States to launch a nuclear war, I really doubt they would use clean bombs. In fact, the dirtier the better. The people you don’t burn to death you radiate to death.”

Mrs. Canby said, “This is really terrible lunchtime conversation.”

“Exactly my point,” Robert told her. “You would rather believe that our World War Two defenses are adequate, because the alternative is to understand that there isn’t any defense at all.”

Elizabeth said, “But that doesn’t seem to matter, does it? You said a little while ago that there wouldn’t be any Third World War anyway.”

“I was too hasty when I said that,” Robert admitted. “Then I was reminded of Hitler.”

Howard said, “But a Hitler isn’t very likely at this point in history. Not in Russia, anyway. What Bradford said before about fiscal policy is what does it. Russia isn’t poor enough. You have to have an advanced industrial nation that happens to be very poor before you have a people who’ll produce a Hitler, and that just isn’t a description of today’s Russia.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Power Play»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Power Play» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Power Play» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.