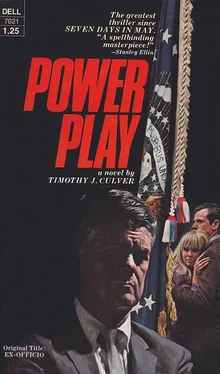

Timothy Culver - Power Play

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Timothy Culver - Power Play» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1971, ISBN: 1971, Издательство: Dell Books, Жанр: roman, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Power Play

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1971

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0440070214

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Power Play: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Power Play»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Occupation: Former President of the United States

Problem: Obsessive desire for power.

Loved and hated more than any man on earth, commanding absolute loyalty from the men and women who once had served him, defying the government he once had headed, Bradford Lockridge pursued his final and possibly insane vision of glory...

Power Play — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Power Play», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Yes,” said the man. “Now, we can’t offer you television or radio, not even in-flight films, but we do have — shall we go back to the lounge, Mrs. Canby?”

She didn’t move till he tentatively touched her elbow, and then she walked obediently back to the lounge and just stood there. Bradford was sitting on a padded chair near a window, looking out with a pleased smile on his face.

The man said, “Mrs. Canby, it would be better if you sat down during take-off.”

“Yes,” she said, and backed into a sofa, and sat down. She watched Bradford’s happy profile as the plane gathered its strength and ran up into the sky.

v

A jounce awoke her, and she sat up in the bed, instantly aware of everything that had happened and disgusted with herself for having been able to sleep.

After the plane had taken off, she had continued to sit there in the lounge for a while, unable any more even to hope that Wellington was responsible for all this. Bradford and the brown-uniformed man — beneath his overcoat he wore a military-type brown jacket, but without insignia — had chatted about advances in aeronautics and similar topics, and when Evelyn reached the point where she was sure she was going to start screaming she forced herself to totter to her feet instead and to say, her voice scratchy and uncertain, “I’m going to take a nap.”

“Poor girl,” Bradford said, smiling at her, “you haven’t had much sleep, have you? Have a good long rest, I’ll see you later.”

But she hadn’t expected to sleep. She’d come back here only to let her tautly held nerves do whatever they wanted to do, and what they’d wanted to do, it turned out, was express themselves in weeping. She had, in effect, cried herself to sleep.

And now a jouncing had awakened her. She looked out the small round window beside the bed, and they were on the ground again. Was it Reykjavik once more? No, it wasn’t, there was more snow and fewer lights; whatever this place was, it was smaller than Reykjavik and probably farther north.

She got up as the plane taxied toward distant low buildings, and spent a futile time trying to smooth the wrinkles from her skirt. Finally she gave up and moved forward into the corridor.

There was only a tiny hand-sink in the latrine, so she washed her face and hands at the galley sink and reconstructed her makeup with the aid of the small mirror in her compact. She then looked at her watch, which said seven-thirty. What would that be now, morning or evening? Evening, she thought. Seven-thirty in the evening in Eustace. God alone knew what time it was here, but it had taken nearly six hours to get here.

She went out to the lounge, and Bradford and the brown-uniformed man were sitting across from one another at one of the built-in tables. There were maps spread out on the table. Bradford looked up cheerfully and said, “They’re refueling. We’ll be here about half an hour.”

“Where are we?”

“Prince Rupert, British Columbia. Come take a look.”

She sat down beside him, and he showed her on one of the maps, a Mercator projection of the world. They had started from Iceland, in the North Atlantic, and they had flown over Greenland, over Hudson’s Bay and over all of northern Canada. They had now landed at Prince Rupert, a small city on the Pacific coast of Canada, just south, of the Alaskan border. And from here? There was one last lap of the journey to go, approximately as long as the one they’d just completed; when they took off, thirty minutes from now, they would cross the North Pacific, keeping just south of the Aleutians, would turn to a somewhat more southerly course just before reaching the Kamchatka Peninsula (an extension of the Soviet Union), would cross Hokkaido (the northernmost island of Japan) from northeast to southwest, would fly over the Sea of Japan and a segment of North Korea, and then would have a quick run inland over China to Peking. “We’ll be there in seven hours,” Bradford said. He was smiling from ear to ear. “Perhaps six.”

I’m going to die, Evelyn thought. I am going to scream, and lose my sanity, and die.

“I’m starved,” Bradford said. “Evelyn? Would you mind?”

“Not at all,” she said. She got to her feet and went to the galley and began to look over the available foods.

vi

There was no more sleep. There was no more hope. There was no more anything. The plane traveled through high darkness, nothing to be seen outside the window but her own haggard reflection, and she thought, I’ll maneuver Bradford to the doorway, I’ll get the door open, I’ll put my arms around him and push us both out. But she did nothing.

She could tell when they were over land again at last; occasional lights glittered below. Whether they were so few because it was late at night in China or because there were clouds frequently in the way she couldn’t tell. What time would it be in China now? According to her watch, it was after midnight in Eustace. Unless that was confused, too, unless her watch was trying to tell her that noon had just been passed on the east coast of the United States.

She couldn’t think any more, she didn’t even want to think any more, and when the plane began at last to circle, when she could feel that they were making their landing approach, she felt nothing but the kind of hollowness, despair, that comes on the heels of a total defeat.

Airport lights are the same all over the world, strings of white lights intersected by strings of blue or red or amber, all making a non-representational pattern in the dark.

The pattern rushed suddenly closer, the plane bumped, it hurtled along the runway and gradually slowed.

There were low buildings far away across the strings of lights, but the plane didn’t move in that direction. Nose high, wings cumbersomely spread, it walked the other way instead, toward the outer edge of the pattern of lights, where there was nothing but darkness.

The man in the brown uniform was saying, “You understand, of course, that you’ll have to be under total security for at least the time being. The United States government undoubtedly knows by now that you managed to elude them, and I doubt they’ll waste any time dispatching assassination teams.”

“That’s unfortunately true, I suppose,” Bradford said. He looked momentarily grim, but then brightened. “But we hope to be able to change all that eventually, don’t we?”

“Yes, sir,” the uniformed man said soberly.

“We can put up with a little inconvenience meantime,” Bradford said.

The plane came to a stop. The other man reappeared from the front of the plane, and opened the door. He put the metal steps out, and turned to extend his hand toward Bradford’s and say, “I want you to know I’m proud to have had a part in this, sir.”

“Thank you,” Bradford said, smiling, shaking his hand, while Evelyn thought, Proud? To turn against your own country, your own people?

They stepped down out of the plane, Bradford first, Evelyn behind him, and she was suddenly reminded of that other plane ride at the beginning of all this, when they had flown together to California, when they had arrived at Harrison’s fake little town in a business jet very like this one (but somewhat smaller, and much less elaborately laid out), and Bradford had gone out to sunlight and scattered cheers and his first cerebral attack. A poster-bedecked hansom cab had been waiting for them that time, at the foot of the steps.

This time? A black truck, its windowless rear doors open. And half a dozen uniformed Chinese soldiers, bulky in their quilt like coats, carrying rifles in their hands.

The chill that Evelyn felt had nothing to do with the breeze that came through her cloth coat.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Power Play»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Power Play» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Power Play» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.