‘But you weren’t even with your brother when he killed that young girl.’

‘Yes, I was,’ said André. ‘Allow me to explain. My brother and I had been out earlier that evening celebrating his twenty-first birthday, and both of us had a little too much to drink. When we were finally thrown out of the last bar, Guillaume passed out, so I had to drive him home.’

‘But the police found him behind the wheel.’

‘Only because I’d careered onto a pavement and hit a girl, a girl I taught, who later died. Would she still be alive today if I hadn’t run away but stopped and called for an ambulance? But I didn’t. Instead I panicked and drove quickly away, purposely crashing the car into a tree not too far from Guillaume’s home. When the police eventually arrived, they found my brother behind the wheel and no one else in the car.’

‘But that was exactly what the police did find,’ said Father Pierre.

‘The police found what I wanted them to find,’ said André. ‘But then they had no way of knowing. I had climbed out of the car, pulled my brother across to the driver’s seat, and then abandoned him with his head resting on the steering wheel, the horn blaring out for all to hear.’

The priest crossed himself.

‘I made my way quickly back to my own flat on the other side of town, slipping in and out of the shadows, to make sure no one saw me, although there weren’t many people around at that time in the morning. When I eventually got home, I let myself in through the back door, crept upstairs and went to bed. But I didn’t sleep. Truth is, I haven’t had a good night’s sleep since.’

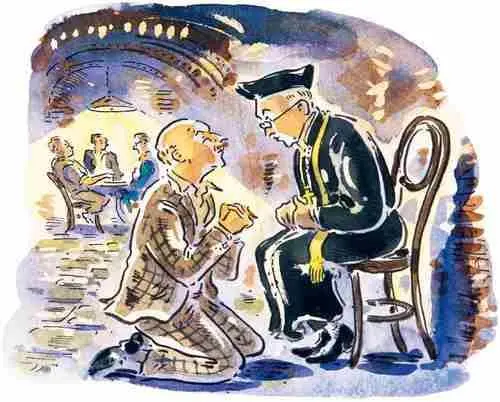

The headmaster put his head in his hands and remained silent for some time, before he continued.

‘I waited for the police to knock on my door in the middle of the night, arrest me and lock me up, but they didn’t, so I knew I’d got away with it. After all, it was Guillaume they discovered behind the wheel, only a hundred metres from his home. The following day, several witnesses confirmed they’d seen him the night before, and he was in no fit state to drive.’

‘But the police must eventually have interviewed you?’

‘Yes, they visited the school the following morning,’ admitted André.

‘When you could have told them it was you who was driving the car, and not your brother.’

‘I told them I’d had a little too much to drink so walked home, and that was the last time I’d seen him.’

‘And they believed you?’

‘And so did you, Father.’

The priest bowed his head.

‘The local paper had a field day. Photos of a pretty young girl with her whole life ahead of her. A headline that remains etched in my memory to this day. A crashed car, and a young man being dragged out of the front seat at two in the morning. The only mention I got was as the poor unfortunate brother, whom they described as a popular and respected young teacher from the local college. I even attended the girl’s funeral, only exacerbating my crime. By the time it came to the trial, the verdict had been decided long before the judge passed sentence.’

‘But the trial was several months later, so you still could have told the jury the truth.’

‘I told them what they’d read in the papers,’ said André, his head bowed.

‘And your brother was sentenced to six years?’

‘He was sentenced to life, Father, because the only job he could get after he came out of prison was as a janitor in the school, where I was able to pull a few strings. Few remember that Guillaume was training to be an architect at the time, and had a promising career ahead of him, which I cut short. But now I’ve been granted one last chance to put the record straight,’ said André, looking up at the priest for the first time. ‘I want you to promise me, Father, that after they hang me tomorrow, you will tell everyone who attends my funeral what actually happened that night, so that my brother can at least spend the rest of his days in peace and not continue to take the blame for a crime he didn’t commit.’

‘Perhaps Our Lord will decide to spare you, my son,’ said the priest, ‘so you can tell the world the truth and begin to understand what your brother must have suffered for all these years.’

‘I would rather die.’

‘Perhaps we should leave that decision to the Almighty?’ the priest said, as he bent down and helped the headmaster back onto his feet. André turned and walked slowly away, his head still bowed.

‘What can he possibly have told Father Pierre that we didn’t already know about?’ said the mayor when he saw André collapse onto his bunk and turn his face to the wall, like a badly wounded soldier who knows nothing can save him.

The priest turned his attention to those still seated at the table.

‘Which one of you will be next?’ he asked.

The mayor dealt three cards.

CLAUDE TESSIER, THE BANKER

‘Forgive me, Father, for I have sinned,’ said Claude. ‘I wish to seek God’s understanding and forgiveness.’

‘Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of Heaven.’ Father Pierre couldn’t recall when Tessier had last attended church, let alone confession, although there wasn’t much he didn’t know about the man. However, there remained one mystery that still needed to be explained, and he hoped that the thought of eternal damnation might prompt the banker to finally admit to the truth.

Claude Tessier had become chairman of the family bank when his father died in 1940, only days before the Germans marched down the Champs-Elysées. Lucien Tessier had been both respected and admired by the local community. Tessiers might not have been the largest bank in town, but Lucien was trusted, and his customers never doubted that their savings were in safe hands. The same could not always be said of his son.

The old man had admitted to his wife that he wasn’t sure Claude was the right person to follow him as chairman. ‘Feckless and foolhardy’ were the words he murmured on his deathbed, and then whispered to the priest that he feared for the widow’s mite when he was no longer there to oversee every transaction.

Lucien Tessier’s problems were compounded by having a daughter who was not only brighter than Claude, but also honest to the degree of embarrassment. However, the old man realized that Saint Rochelle was not yet ready to accept a woman as chairman of the bank.

Claude’s only other banking rival in the town was Bouchards, a well-run establishment that the old man admired. Its chairman, Jacques Bouchard, also had a son, Thomas, who had already proved himself well worthy of succeeding him.

Claude Tessier and Thomas Bouchard had advanced through life together, admittedly at a different pace on their predestined course. School, national service, and later university, before returning to Saint Rochelle to begin their banking careers.

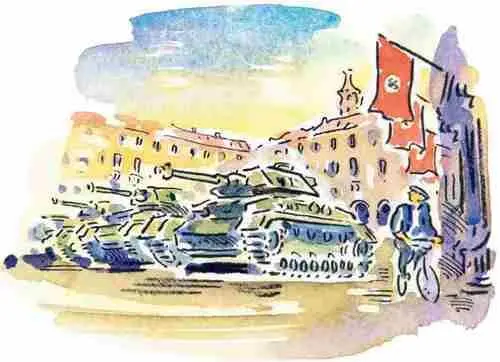

It was Bouchard’s father’s idea, and one he quickly regretted, that the two boys should serve their apprenticeships at rival banks. Claude’s father happily agreed to the arrangement, and got the better deal. After two years, Bouchard never wanted to set eyes on young Claude again, while Lucien wished Thomas would join him on the board of Tessiers. Nothing much changed as both boys progressed towards becoming chairman of their banks; that is until the Germans parked their tanks in the town square.

Читать дальше

![Джеффри Арчер The Short, the Long and the Tall [С иллюстрациями] обложка книги](/books/388600/dzheffri-archer-the-short-the-long-and-the-tall-s-cover.webp)