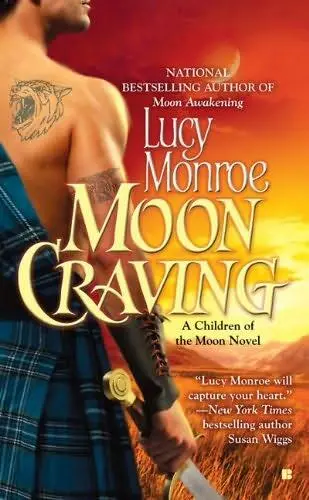

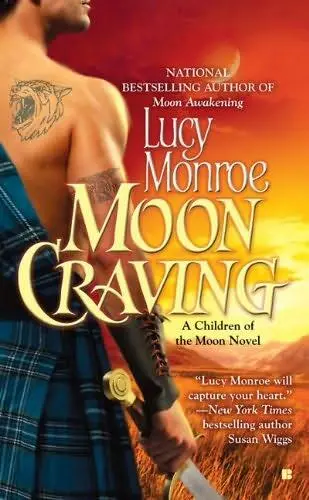

Moon Craving

(The second book in the Children of the Moon series)

Lucy Monroe

For all of the readers who asked and e-mailed about this book. Your enthusiasm for this world and desire to read the next story blessed me so much. Hearing from you helped me to keep working on it even when so many other things were vying for my attention. And I thank you! I sincerely hope Talorc and Abigail’s story is worth the wait. It was a very special story for me to write and one that I hope connects with all your hearts!

Hugs and blessings,

Lucy

Millennia ago God created a race of people so fierce even their women were feared in battle. These people were warlike in every way, refusing to submit to the rule of any but their own . . . no matter how large the forces sent to subdue them. Their enemies said they fought like animals. Their vanquished foes said nothing, for they were dead.

They were considered a primitive and barbaric people because they marred their skin with tattoos of blue ink. The designs were usually simple. A single beast was depicted in unadorned outline, though some clan members had more markings, which rivaled the Celts for artistic intricacy. These were the leaders of the clan and their enemies were never able to discover the meanings of any of the blue-tinted tattoos.

Some surmised they were symbols of their warlike nature, and in that they would be partially right. For the beasts represented a part of themselves these fierce and independent people kept secret at the pain of death. It was a secret they had kept for the centuries of their existence while most migrated across the European landscape to settle in the inhospitable north of Scotland.

Their Roman enemies called them Picts, a name accepted by the other peoples of their land and lands south . . . they called themselves the Chrechte.

Their animal-like affinity for fighting and conquest came from a part of their nature their fully human counterparts did not enjoy. For these fierce people were shape-changers and the bluish tattoos on their skin were markings given as a right of passage. When their first change took place, they were marked with the kind of animal they could change into. Some had control of that change. Some did not. And while the majority were wolves, there were large hunting cats and birds of prey as well.

None of the shape-shifters reproduced as quickly or prolifically as their fully human brothers and sisters. Although they were a fearsome race and their cunning was enhanced by an understanding of nature most humans do not possess, they were not foolhardy and were not ruled by their animal natures.

One warrior could kill a hundred of his foe, but should she or he die before having offspring, the death would lead to an inevitable shrinking of the clan. Some Pictish clans and those recognized by other names in other parts of the world had already died out rather than submit to the inferior but multitudinous humans around them.

Most of the shape-changers of the Scots Highlands were too smart to face the end of their race rather than blend with others. They saw the way of the future. In the ninth century AD, Keneth MacAlpin ascended to the Scottish throne. Of Chrechte descent through his mother, MacAlpin was the result of “mixed” marriage, and, his human nature had dominated. He was not capable of “the change,” but that did not stop him from laying claim to the Pictish throne (as it was called then). In order to guarantee his kingship, he betrayed his Chrechte brethren at a dinner, killing all of the remaining royals of their people—and forever entrenched a distrust of humans by their Chrechte counterparts.

Despite this distrust, the Chrechte realized that they could die out fighting an ever increasing and encroaching race of humanity, or they could join the Celtic clans.

They joined.

As far as the rest of the world knew—though much existed to attest to their former existence—what had been considered the Pictish people were no more.

Because it was not in their nature to be ruled by any but their own, within two generations, the Celtic clans that had assimilated the Chrechte were ruled by shape-changing clan chiefs, though most of the fully human among them did not know it—only a sparse few were trusted with the secrets of their kinsmen. Those who knew were aware that to betray the code of silence meant certain and immediate death.

That code of silence was rarely broken.

We, the most distant dwellers upon the earth, the last

of the free, have been shielded . . . by our remoteness

and by the obscurity which has shrouded our name . . .

Beyond us lies no nation, nothing but waves and rocks.

—KING CALGACUS OF THE PICTS, THIRD CENTURY AD

“Is it war then?” the grizzled old Scot, Osgard, asked his laird.

Barr, second-in-command to their powerful leader, frowned. “On our own king?”

The temptation to say yes was great. Talorc, Laird of the Sinclair clan and alpha to his Chrechte pack, had to clamp his jaw tight to keep the word from coming out. It would serve David right. Talorc had no doubt that if he ordered them to, his clan would go to war against the king still disputed as ruler over all Scotland by many Highlanders.

In the Highlands, at least, first loyalty still went to the clan leader, not the king. Where would that leave the “civilized” king then?

But the man raised by Normans in that hellhole to their south was a friend. Despite the Sassenach influence, Talorc respected King David, when few men earned that honor.

“Was it not enough he sent you one English bride, that he now sends you another?” Osgard asked, his aged voice still strong enough to express his fury.

“He has no plans to send this one,” Barr said.

As if Talorc didn’t already know the details of the damn message. “No, he expects me to travel to England to wed this woman.”

“’Tis an outrage,” Osgard growled.

Barr nodded. “An offense you canna take lightly.”

“According to the messenger, ’twas both King David and England’s king who took offense you did not marry the first Englishwoman,” Guaire, Talorc’s seneschal, quietly inserted, earning himself a sulfuric glare from Osgard.

The old man, who had stood in Talorc’s father’s stead as advisor since his death, deliberately turned so Guaire was no longer in his line of sight. “Some might care about offense to the Sassenach king, but there are those of us that know better than to trust the English. Especially one who seeks to be wife to our laird.”

“I am concerned about neither king’s displeasure, but merely point out that they were offended first and that might explain our own king’s unpleasant request.” Guaire stood his ground, but it was clear the young soldier was bothered by Osgard’s comment.

Osgard harrumphed and Barr kept his own council, but Talorc nodded. “No doubt. I had no intention of marrying the Englishwoman Emily, and ’tis clear my overlord realized that after the fact.”

“You did not go to war when the Balmoral took and kept her,” Barr said.

“A Chrechte does not go to war over the loss of a Sassenach ,” Osgard spit out, disgust lacing every word.

Guaire frowned. “The Balmoral would.”

Talorc’s seneschal was right. The leader of the Balmoral clan, now married to the Englishwoman his king had first bid him wed, would no doubt go to war over her. As impossible as it might be for Talorc to understand, all indications led him to believe the other Chrechte laird loved his outspoken wife.

Читать дальше