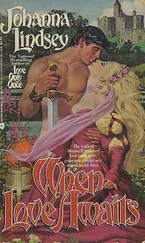

Johanna Lindsey

When Love Awaits

Dedicated to Vivian and Bill Walje, my second parents

England, 1176.

SIR Guibert Fitzalan leaned back against the thick tree trunk, watching two maidservants pack away the remains of the picnic lunch. A man of moderately good looks, he was an unassuming man and women, even his liege lady's serving women, had a way of unnerving him. Wilda, the younger of the two servants, caught his eye just then. Her bold look made him look quickly away, heat burning his face.

Spring was in full flower and Wilda was not the only woman to turn her eye on Sir Guibert appreciatively. Nor was he the only man who received one of her hot gazes. Wilda was decidedly comely, with a sleek little nose and rosy cheeks. Her hair was a glossy chestnut, and she was equally blessed with a lush body.

Even so, Guibert was a confirmed bachelor. Besides that, Wilda was too young for a man of two score and five years. Why, she was as young as Lady Leonie whom they both served, and that lady was just nineteen.

Sir Guibert thought of Leonie of Montwyn as a daughter. At that moment, as he observed her leaving the pasture where she had begun her spring herb gathering and disappearing into the woods, he sent four of his men-at-arms to follow her at a discreet distance. He'd brought along ten men to protect her, and the soldiers knew better than to grumble at the duty, but it was hardly their favorite. Leonie often asked them to pick plants as she pointed them out. Herb gathering was not manly.

Before this spring, three guards had been enough to accompany Lady Leonie, but now there was a new resident at Crewel, into whose woods Leonie entered to search for herbs. The new lord of all the lands of Kempston was a matter of great concern to Sir Guibert.

Guibert had never liked the old lord of Kempston, Sir Edmond Montigny, but at least the old baron had caused no trouble. The new lord of Kempston made endless complaints against the Pershwick serfs and had done so ever since taking possession of Crewel Keep. It helped not at all that the complaints might be valid. Worse, Lady Leonie felt personally responsible for her serfs' misdeeds.

"Let me see to this, Sir Guibert," she had begged him when she first heard of the complaints. "I fear the serfs believe they are doing me a service by stirring up mischief at Crewel."

For explanation, she confessed, "I was in the village the day Alain Montigny came to tell me what befell his father and himself. Too many of the serfs saw how upset I was and I fear they heard me wish a pox on Black Wolf, who now rules Crewel."

Guibert found it hard to believe that Leonie would curse anyone. Not Leonie. She was too good, too kind, too quick to mend any ill, ease any burden. But then, for Sir Guibert, she could do no wrong. He doted on and spoiled her. And, he asked himself, if he did not, who would? Certainly not her father, who had sent her from him six years ago, when her mother died, banishing Leonie to Pershwick Keep along with her mother's sister, Beatrix, because he could not bear the sight of anyone who reminded him of his beloved wife.

Guibert could not fathom the man's action, but then he had never known Sir William of Montwyn very well, even though he had come to live in his household as part of Lady Elisabeth's dowry when she wed Sir William. Lady Elisabeth, an earl's daughter and the fifth and youngest of her father's children, had been allowed a love match. The man was in no way her equal, but Sir William loved her—perhaps too much. Her death destroyed him, and he apparently could not bear the presence of his only child. Leonie, like Elisabeth, was small and slender, fair, and blessed with extraordinary hair of silver-blond and silver-gray eyes. "Beautiful" was not adequate to describe Leonie.

He sighed, thinking of the two women, mother and daughter, one gone, the other just as dear to him as her mother had been. And then he froze, pleasant musings shattered by a battle cry, a cry of rage coming from the woods.

Guibert was frozen for no more than a second before he was running toward the woods, his sword already drawn. Four men-at-arms who'd been standing nearby with the horses chased after him, everyone hoping that the men with Leonie had stuck close by her.

Deep in the woods, Leonie of Montwyn had also been stunned for a moment by the unearthly cry. She had, as usual, managed to put a good distance between herself and her four protectors. Now, she imagined some great demonic beast was nearby. Still, her inborn, unladylike curiosity urged her on toward the sound instead of back to her men.

She smelled smoke and broke into a full run, pushing through shrubs and trees until she found the source of the smoke. A woodcutter's hut had burned. The woodcutter was staring at the smoldering remains of his home as five mounted knights and fifteen men-at-arms, also mounted, sat silently facing the ruined hut. An armored knight paced his great destrier back and forth between the hut and the men. He let out an explosive curse while Leonie watched and then she knew where the first horrible sound had come from. She knew, too, who the knight was. She moved back into the bush, out of sight, thankful for her concealing dark green mantle.

Concealment was jeopardized as her men came running behind her.

Leonie quickly turned toward them, hushing them and motioning them back. She made her way to them silently, and they positioned themselves around her, then moved back toward her land. Sir Guibert and the rest of the men were upon them a moment later.

"There is no danger," she assured Sir Guibert. "But we should leave this place. The lord of Kempston has found a woodcutter's hut burned to the ground and I think he is none too pleased."

"You saw him?"

"Yes. He is in a fine rage."

Sir Guibert grunted and hurried Leonie along. It would not do for her to be found near the burned hut with her men-at-arms. How would she talk her way out of that?

Later, when it was safe, serfs could return to the woods and retrieve Leonie's plants. For now, Lady Leonie and the armed men had to be removed from the scene.

As Sir Guibert lifted her into her saddle, he asked, "How do you know it was the Black Wolf you saw?"

"He wore the silver wolf on a black field."

Leonie did not say that she had seen the man once before. She could never tell Sir Guibert that, for she had disguised herself and sneaked out of the keep without his knowing, to go to the tourney at Crewel. Later, she'd wished she hadn't.

"Most like it was him, though his men also wear his colors," Sir Guibert agreed, remembering that awful bellow. "You saw what he looks like?"

"No." She could not quite keep the disappointment from her voice.

"He wore his helmet. But he is huge, of that there was no mistaking."

"Perhaps this time he will come himself and see the trouble ended instead of sending his man over."

"Or he will bring his army."

"He has no proof, my lady. It is one serf's word against another's. But get you safe inside the keep now. I will follow with the others and see the village guarded."

Leonie rode for home with four men-at-arms and her two maids. She saw that she had not been firm enough in warning her people against causing more trouble with the Crewel serfs. In truth, her heart had not been in the warning, for it gave her satisfaction to know the new lord of Kempston was being plagued with domestic problems.

She had thought to soften the situation with her people by offering entertainments at Pershwick on the next feast-day. But her anxiety over the Black Wolf and what he might do next made her decide against any gathering at her keep. No, she was better off keeping a weather eye on her neighbor's activities and offering no chance for her people to gather where there was bound to be drink. They might, she knew, decide to plan something that could easily rebound on her. No, if her villagers were going to plot against the Black Wolf, she would be better off if they did so far from her.

Читать дальше