Outside the cry of “Burn the adulteress! Burn the murderess!” was chanted through the streets.

ANOTHER day came. She went to the window, her long hair covering her bare shoulders.

“Good people …” she cried. “Good people …”

But their only answer was: “Burn her. Burn the murderess of her husband!”

The dreadful banner was before her eyes. She wept and stormed. Then she saw Lord Maitland passing along the street. She called to him. He would have looked away but the sight she presented was so terrible that out of pity he was forced to turn back.

“Come here, Maitland,” she cried. “Come here.”

He knew that if he followed his inclination to hurry away he would be haunted by the memory of her eyes forever.

She looked at him—the husband of her dear Flem—and one of those who had betrayed her. How wicked was the world, how cruel!

“So you are with them now?” she called. “So you are with my enemies, Maitland?”

“Madam,” he answered, “I served you well until you chose others who you thought would serve you better.”

He had never forgiven her for supplanting him with David. He would never forgive her for her marriage with Bothwell.

She cried: “Did you not know then of the plot to murder Darnley! Were you not in the plot, my lord?”

His answer was: “Madam, you destroyed yourself when you took Bothwell for husband. Had you not become his slave and the slave of your own passion, you would not now stand guilty of murder.”

The crowd roared: “Burn the murderess!”

Maitland averted his eyes and passed on.

In that moment she knew that all who had planned to murder Darnley were against her. They would—as Maitland would—revile her, doing their utmost to put all the guilt on her shoulders and those of her lover, that investigations should not be made concerning themselves. The murder of Darnley—like the murder of Rizzio—would be shown to the Scots and the world not as a political murder, but as a crime passionel.

She was lost. She knew it. Maitland had had some honor in the old days. He had been one of those whom she could trust; but Maitland was ready to save his own life and his political rewards at the cost of the reputation, and perhaps the life, of the Queen.

SHE LIVED through another day of torment, and that evening, because they feared for her reason, they took her from the provost’s house to Holy-rood. She was forced to walk as a captive with Morton on one side of her, Atholl on the other, while the soldiers marched with them to protect her from the murderous rabble. As she walked the odious banner was held before her eyes and she prayed for death.

But in Holyrood some comfort awaited her, for there she found some of her women, and among them those two loved ones, Mary Seton and Mary Livingstone.

She wept in their arms and they swore that they would not leave her; they would die with her and for her if need be.

But her captors did not intend her to stay at Holyroodhouse. Late that night she was hurried out of the palace and, hysterical and exhausted with misery and fatigue, she was taken through the darkness to Lochleven where her jailors would be the Douglases—Sir William and his wife who was Moray’s mother.

And there, in the ancient castle on an island in the centre of a lake, Mary Stuart came to the end of her turbulent reign, for that night she passed into the half-light, a prisoner. She was twenty-four years of age and had many years left to her, but her life as Queen was virtually over.

Mary, Queen of Scotland and the Isles, had become Mary, the captive.

IT WAS the month of February, and in her apartment in Fotheringhay Castle the Queen was dividing her possessions into separate piles. There was a little money and some trinkets—not very much left after twenty years of prison—and there were so many to whom she wished to leave some token, some memory of herself.

She was very tired; she had lived little more than forty-four years but it seemed twice as long.

She looked at that dark corner in which one of her ladies—her dear Jane Kennedy—sat silently weeping, rocking her body to and fro in the agony of her grief.

Elizabeth Curie, another of those who had been with her in many of her doleful prisons and who loved her, did not weep, but her grief was manifest in every line of her body. The others had run from the chamber, for they could not control their sobbing.

“My children, my children,” said the Queen softly, “it is not a time to weep. You should rather rejoice to see me on a fair road of deliverance from the many evils and afflictions which have so long been my portion.”

They did not answer her; and her thoughts traveled back to that road along which she had come. So many years ago it had been since she had said good-bye to her lover. Twenty years! And she had not seen him since that day. He had become but a memory to her, a memory that was both sweet and bitter.

Life had been little kinder to him than to her. He had escaped to Denmark, but not to freedom. Anna Throndsen had forgotten the love she had once had for him and had sued him in the courts for money she had given him in the past. Mary’s family, the Guises, would not allow a man who had ruined their niece to regain his freedom. They had arranged with Denmark that he should be imprisoned in the Castle of Malmoe, and there he had spent ten weary years. He had died at length, of melancholy, it was said; half mad with frustration, he, the strong man, confined within four walls would dash his head in very desperation against those walls; he too had been glad to die. And before he had died he had written a confession declaring her innocent of Darnley’s murder although he himself had played a large part in it. That confession had brought great comfort to Mary in Chatsworth—where she had been imprisoned at that time—for it brought with it a vivid reminder of that immense strength which was without fear. Poor Bothwell! Poor lover, who had once believed the world was his to conquer and subdue. Ambition had ruined him as certainly as passion had ruined her.

But that was all long ago, and there was no need to dwell upon it, for soon she would be past all earthly pain.

Memories of Lochleven came to her—of George and Willie Douglas who had loved her and sought to help her escape from her prison. It came back to her in clear brief pictures: Lochleven where she had been forced to sign her abdication and had known that her son had become the King of Scotland; Lochleven where she had given birth to twins—hers and Bothwell’s—stillborn and so tragically symbolic; Lochleven from where she had all but escaped dressed as a laundress, and had been betrayed because a boatman had seen her beautiful hands which could never have belonged to a laundress. But it was at Lochleven that George and Willie Douglas had loved her and had determined to give their lives if need be for her sake, so that eventually, with their aid she had escaped, but alas! only to Langside and utter defeat at the hands of her brother Moray’s troops.

She had known then that her only hope was flight from Scotland, but where could she seek refuge? She must be a fugitive from her own land; her son was lost to her, brought up by her enemies to believe the worst of her; her own brother was determined on her defeat and offered her nothing but a prison or death.

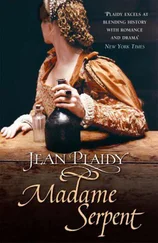

Could she go to France? she had asked herself. She thought of her family there. But France was ruled by an evil woman, a woman who had never shown herself to be Mary’s friend. How could she throw herself on the mercy of Catherine de Médicis?

There was only one to whom she could appeal for mercy—the Queen of England; and so for more than eighteen years she remained the prisoner of Elizabeth. She had asked for hospitality and had been given captivity. And during those years there had been one subject which had always been raised when her name was mentioned: the subject of the Casket Letters.

Читать дальше