Once any of the error bits in a stream’s state are set, they remain set, which is not always what you want. When reading a file for example, you might want to reposition to an earlier place in the file before end-of-file occurred. Just moving the file pointer doesn’t automatically reset eofbitor failbit; you have to do it yourself with the clear( )function, like this: .

myStream.clear(); // Clears all error bits

After calling clear( ), good( )will return trueif called immediately. As you saw in the Dateextractor earlier, the setstate( )function sets the bits you pass it. It turns out that setstate( )doesn’t affect any other bits—if they’re already set, they stay set. If you want to set certain bits but at the same time reset all the rest, you can call an overloaded version of clear( ), passing it a bitwise expression representing the bits you want to set, as in: .

myStream.clear(ios::failbit | ios::eofbit);

Most of the time you won’t be interested in checking the stream state bits individually. Usually you just want to know if everything is okay. This is the case when you read a file from beginning to end; you just want to know when the input data is exhausted. In cases such as these, a conversion operator is defined for void*that is automatically called when a stream occurs in a Boolean expression. To read a stream until end-of-input using this idiom looks like the following: .

int i;

while (myStream >> i)

cout << i << endl;

Remember that operator>>( )returns its stream argument, so the whilestatement above tests the stream as a Boolean expression. This particular example assumes that the input stream myStreamcontains integers separated by white space. The function ios_base::operator void*( )simply calls good( )on its stream and returns the result. [41] It is customary to use operator void*(В ) in preference to operator bool(В ) because the implicit conversions from bool to int may cause surprises, should you errantly place a stream in a context where an integer conversion can be applied. The operator void*(В ) function will only implicitly be called in the body of a Boolean expression.

Because most stream operations return their stream, using this idiom is convenient .

Iostreams existed as part of C++ long before there were exceptions, so checking stream state manually was just the way things were done. For backward compatibility, this is still the status quo, but iostreams can throw exceptions instead. The exceptions( )stream member function takes a parameter representing the state bits for which you want exceptions to be thrown. Whenever the stream encounters such a state, it throws an exception of type std::ios_base::failure, which inherits from std::exception .

Although you can trigger a failure exception for any of the four stream states, it’s not necessarily a good idea to enable exceptions for all of them. As Chapter 1 explains, use exceptions for truly exceptional conditions, but end-of-file is not only not exceptional—it’s expected ! For that reason, you might want to enable exceptions only for the errors represented by badbit, which you would do like this: .

myStream.exceptions(ios::badbit);

You enable exceptions on a stream-by-stream basis, since exceptions( )is a member function for streams. The exceptions( )function returns a bitmask [42] An integral type used to hold single-bit flags.

(of type iostate, which is some compiler-dependent type convertible to int) indicating which stream states will cause exceptions. If those states have already been set, an exception is thrown immediately. Of course, if you use exceptions in connection with streams, you had better be ready to catch them, which means that you need to wrap all stream processing with a tryblock that has an ios::failurehandler. Many programmers find this tedious and just check states manually where they expect errors to occur (since, for example, they don’t expect bad( )to return truemost of the time anyway). This is another reason that having streams throw exceptions is optional and not the default. In any case, you can choose how you want to handle stream errors .

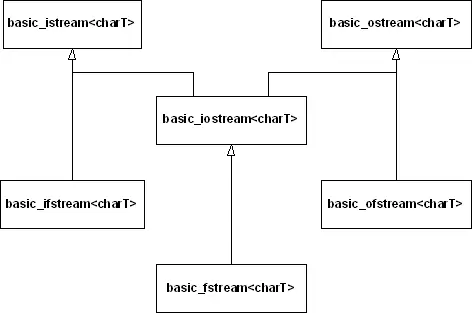

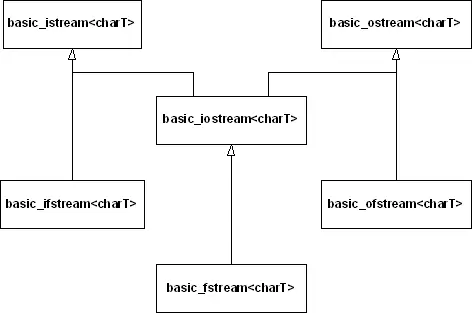

Manipulating files with iostreams is much easier and safer than using stdioin C. All you do to open a file is create an object; the constructor does the work. You don’t have to explicitly close a file (although you can, using the close( )member function) because the destructor will close it when the object goes out of scope. To create a file that defaults to input, make an ifstreamobject. To create one that defaults to output, make an ofstreamobject. An fstreamobject can do both input and output .

The file stream classes fit into the iostreams classes as shown in the following figure.

As before, the classes you actually use are template specializations defined by type definitions. For example, ifstream, which processes files of char, is defined as .

typedef basic_ifstream ifstream;

A File-Processing Example

Here’s an example that shows many of the features discussed so far. Notice the inclusion of to declare the file I/O classes. Although on many platforms this will also include automatically, compilers are not required to do so. If you want portable code, always include both headers .

//: C04:Strfile.cpp

// Stream I/O with files

// The difference between get() & getline()

#include

#include

#include "../require.h"

using namespace std;

int main() {

const int sz = 100; // Buffer size;

char buf[sz];

{

ifstream in("Strfile.cpp"); // Read

assure(in, "Strfile.cpp"); // Verify open

ofstream out("Strfile.out"); // Write

assure(out, "Strfile.out");

int i = 1; // Line counter

// A less-convenient approach for line input:

while(in.get(buf, sz)) { // Leaves \n in input

in.get(); // Throw away next character (\n)

cout << buf << endl; // Must add \n

// File output just like standard I/O:

out << i++ << ": " << buf << endl;

}

} // Destructors close in & out

ifstream in("Strfile.out");

assure(in, "Strfile.out");

// More convenient line input:

while(in.getline(buf, sz)) { // Removes \n

char* cp = buf;

while(*cp != ':')

cp++;

cp += 2; // Past ": "

cout << cp << endl; // Must still add \n

}

} ///:~

The creation of both the ifstreamand ofstreamare followed by an assure( )to guarantee the file was successfully opened. Here again the object, used in a situation in which the compiler expects a Boolean result, produces a value that indicates success or failure .

The first whileloop demonstrates the use of two forms of the get( )function. The first gets characters into a buffer and puts a zero terminator in the buffer when either sz-1characters have been read or the third argument (defaulted to '\n') is encountered. The get( )function leaves the terminator character in the input stream, so this terminator must be thrown away via in.get( )using the form of get( )with no argument, which fetches a single byte and returns it as an int. You can also use the ignore( )member function, which has two default arguments. The first argument is the number of characters to throw away and defaults to one. The second argument is the character at which the ignore( )function quits (after extracting it) and defaults to EOF .

Читать дальше