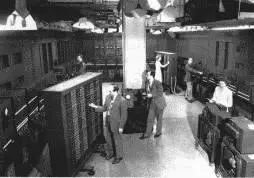

In a 1977 Scientific American article, Bob Noyce, one of the founders of Intel, compared the $300 microprocessor to ENIAC, the moth-infested mastodon from the dawn of the computer age. The wee microprocessor was not only more powerful, but as Noyce noted, “It is twenty times faster, has a larger memory, is thousands of times more reliable, consumes the power of a lightbulb rather than that of a locomotive, occupies 1/30,000 the volume and costs 1/10,000 as much. It is available by mail order or at your local hobby shop.”

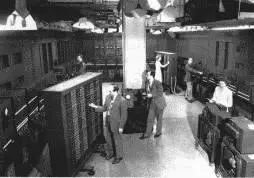

1946: A view inside a part of the ENIAC computer

Of course, the 1977 microprocessor seems like a toy now. And, in fact, many inexpensive toys contain computer chips that are more powerful than the 1970s chips that started the microcomputer revolution. But all of today’s computers, whatever their size or power, manipulate information stored as binary numbers.

Binary numbers are used to store text in a personal computer, music on a compact disc, and money in a bank’s network of cash machines. Before information can go into a computer it has to be converted into binary. Machines, digital devices, convert the information back into its original, useful form. You can imagine each device throwing switches, controlling the flow of electrons. But the switches involved, which are usually made of silicon, are extremely small and can be thrown by applying electrical charges extraordinarily quickly—to produce text on the screen of a personal computer, music from a CD player, and the instructions to a cash machine to dispense currency.

The light-switch example demonstrated how any number can be represented in binary. Here’s how text can be expressed in binary. By convention, the number 65 represents a capital A, the number 66 represents a capital B, and so forth. On a computer each of these numbers is expressed in binary code: the capital letter A, 65, becomes 01000001. The capital B, 66, becomes 01000010. A space break is represented by the number 32, or 00100000. So the sentence “Socrates is a man” becomes this 136-digit string of 1s and 0s:

01010011 01101111 01100011 01110010 01100101 01110011 00100000 01101001 01100001 00100000 01101101 0110000101100001 01110011 0110111001110100 00100000

It’s easy to follow how a line of text can become a set of binary numbers. To understand how other kinds of information are digitized, let’s consider another example of analog information. A vinyl record is an analog representation of sound vibrations. It stores audio information in microscopic squiggles that line the record’s long, spiral groove. If the music has a loud passage, the squiggles are cut more deeply into the groove, and if there is a high note the squiggles are packed more tightly together. The groove’s squiggles are analogs of the original vibrations—sound waves captured by a microphone. When a turntable’s needle travels down the groove, it vibrates in resonation with the tiny squiggles. This vibration, still an analog representation of the original sound, is amplified and sent to loudspeakers as music.

Like any analog device for storing information, a record has drawbacks. Dust, fingerprints, or scratches on the record’s surface can cause the needle to vibrate inappropriately and create clicks or other noises. If the record is not turning at exactly the right speed, the pitch of the music won’t be accurate. Each time a record is played, the needle wears away some of the subtleties of the squiggles in the groove and the reproduction of the music deteriorates. If you record a song from a vinyl record onto a cassette tape, any of the record’s imperfections will be permanently transferred to the tape, and new imperfections will be added because conventional tape machines are themselves analog devices. The information loses quality with each generation of rerecording or retransmission.

On a compact disc, music is stored as a series of binary numbers, each bit (or switch) of which is represented by a microscopic pit on the surface of the disc. Today’s CDs have more than 5 billion pits. The reflected laser light inside the CD player—a digital device—reads each of the pits to determine if it is switched to the 0 or the 1 position, and then reassembles that information back into the original music by generating specified electrical signals that are converted by the speakers into sound waves. Each time the disc is played, the sounds are exactly the same.

It’s convenient to be able to convert everything into digital representations, but the number of bits can build up quite quickly. Too many bits of information can overflow the computer’s memory or take a long time to transmit between computers. This is why a computer’s capacity to compress digital data, store or transmit it, then expand it back into its original form is so useful and will become more so.

Quickly, here’s how the computer accomplishes these feats. It goes back to Claude Shannon, the mathematician who in the 1930s recognized how to express information in binary form. During World War II, he began developing a mathematical description of information and founded a field that later became known as information theory. Shannon defined information as the reduction of uncertainty. By this definition, if you already know it is Saturday and someone tells you it is Saturday, you haven’t been given any information. On the other hand, if you’re not sure of the day and someone tells you it is Saturday, you’ve been given information, because your uncertainty has been reduced.

Shannon’s information theory eventually led to other break-throughs. One was effective data-compression, vital to both computing and communications. On the face of it what he said is obvious: Those parts of data that don’t provide unique information are redundant and can be eliminated. Headline writers leave out nonessential words, as do people paying by the word to send a telegraph message or place a classified advertisement. One example Shannon gave was the letter u , redundant in English whenever it follows the letter q . You know a u will follow each q , so the u needn’t actually be included in the message.

Shannon’s principles have been applied to the compression of both sound and pictures. There is a great deal of redundant information in the thirty frames that make up a second of video. The information can be compressed from about 27 million to about 1 million bits for transmission and still make sense and be pleasant to watch.

However, there are limits to compression and in the near future we’ll be moving ever-increasing numbers of bits from place to place. The bits will travel through copper wires, through the air, and through the structure of the information highway, most of which will be fiber-optic cable (or just “fiber” for short). Fiber is cable made of glass or plastic so smooth and pure that if you looked through a wall of it 70 miles thick, you’d be able to see a candle burning on the other side. Binary signals, in the form of modulated light, carry for long distances through these optic fibers. A signal doesn’t move any faster through fiber-optic cable than it does in copper wire; both go at the speed of light. The enormous advantage fiber-optic cable has over wire is the bandwidth it can carry. Bandwidth is a measure of the number of bits that can be moved through a circuit in a second. This really is like a highway. An eight-lane interstate has more room for vehicles than a narrow dirt road. The greater the bandwidth, the more lanes available—thus, that many more cars, or bits of information, can pass in a second. Cables with limited bandwidth, used for text or voice transmissions, are called narrow-band circuit. Cables with more capacity, which carry images and limited animation, are “midband capable.” Those with a high bandwidth, which can carry multiple video and audio signals, are said to have broadband capacity.

Читать дальше