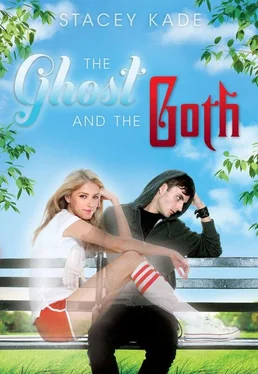

Stacey Kade - The Ghost and the Goth

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Stacey Kade - The Ghost and the Goth» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Hyperion Book CH, Жанр: Юмористическая фантастика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Ghost and the Goth

- Автор:

- Издательство:Hyperion Book CH

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:978-1-4231-4732-9

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Ghost and the Goth: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Ghost and the Goth»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Will Killian — Senior in high school, outcast, dubbed “Will Kill” by the popular crowd for the unearthly aura around him, voted most likely to rob a bank…and a ghost-talker.

The Ghost and the Goth — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Ghost and the Goth», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Did I make it? Did we win? I can’t remember—”

“Thank God, you can see us. We’ve been waiting so long to tell someone—”

I stuck my fingers in my ears to block the voices.

Childish, I know, but it was either that or scream. There were so many of them, and the pleading and the crying ate away at my last nerve. Why wasn’t Mrs. Pederson, the Brit lit teacher, out here breaking this up? She hated “hallway disruptions,” and they were right outside her classroom door. Who were these people anyway? Some of them looked young enough to go to school here, but I’d never seen them before. And with their clothes — can you say fashion crisis? — I would have totally remembered them.

Then I saw a familiar face in the crowd. He’d ditched his mop and bucket somewhere along the way, but I’d recognize that disgusting blue jumpsuit anywhere. My friend, the creepy janitor, was talking to Will.

I lowered my fingers from my ears to try to hear him.

“I didn’t mean to hurt anyone,” he whined, pawing at Will’s shoulder. “You got to tell them that. Those kids …they were asking for it, teasing me like that. Didn’t give that judge no right to kill me.”

Holy crap. He was dead … at least as dead as me. That meant they probably all were: polka-dot girl, tuxedo guy, basketball-player dude, all of them. And every single one of them had gotten to Will Killian before me.

Ugh. I hate waiting in line.

4

Will

All I had to do was make it through the day. Not easy, but possible. I’d survived for years before Dr. Miller had taught me the music trick, something he’d found helped his real schizophrenic patients. Once I got home this afternoon, I’d casually mention that Brewster took away my medically authorized privileges for being under a minute late. The tardy thing would be the only excuse Brewster could offer without adding credence to my “wild stories.” For that, my mom would be on the phone with the school in a flash. It was all about looking like I didn’t need it. Ridiculous, but I knew it would work.

Trouble was, that meant about six hours of torture stood between me and my goal, and Grandpa Brewster wasn’t helping.

“I always knew there was something different about you.” He followed me out of the office, sounding overjoyed. They all do, at first. “I need you to do something for me.”

I tucked my head down and started walking toward my Brit lit class, ignoring him.

“Now, don’t go and do that, kid.” He chased after me. “We both know you can hear me. I just need you to deliver a couple of messages.”

That’s how it starts. Just messages. It sounds simple enough, but wait.

“First, my son, he lives in Florida. I need you to go there and talk to him for me. I want him to know that I’m sorry for all the things I did and said to him…. I didn’t know. I didn’t understand.”

Uh-huh. See? Now not only am I flying out of state, I’m also supposed to talk to a man I’ve never met to explain to him that his dead father wants forgiveness. When I was younger, I used to try to help them, all the ones that talked to me. Obviously, flying out of state to deliver a message wasn’t possible then, either, but I did what I could. It only made things worse, though. The people who didn’t believe me inevitably ended up screaming at me or calling my mom, or worse yet, the cops. The people who did believe would have kept me there for days, crying and pleading with me to stay as a stand-in for their loved one. As a kid, that freaked me out more than the people who shouted at me. No thanks.

“Then, I need you to tell him not to give up on Sonny. I know you and Sonny don’t get along real good, but you have to talk to him, too. Tell him it’s not too late. He doesn’t have to screw it up the way I did.”

Me talk to Sonny, as in Principal Brewster, voluntarily? I don’t think so. I hitched my backpack higher on my shoulders and turned down the hallway to Mrs. Pederson’s class. Maybe she’d have a movie today — something I wouldn’t have to concentrate on while trying to tune out good old Grandpa whispering in my ear.

“It’s important,” Grandpa Brewster insisted. “Please. You’re the only one I’ve found who can do this.”

My resolve wavered a bit. The nice ones were always harder to ignore. I felt bad for them, stuck in that in-between place, watching the world and the consequences of their mistakes but unable to do anything to fix them. I couldn’t get involved, though. They would land me in a mental ward yet, if I let them.

Pulling Mrs. Piaget’s note from my pocket, I pushed open the door to Mrs. Pederson’s classroom, interrupting her midlecture. Great. I couldn’t catch a break today.

I handed her my pass and slipped toward the back of the classroom to my seat. Joonie, in the seat in front of me, turned her head slightly back toward me, pretending to examine the broken and chipped black polish on her fingernails. “Everything okay?” she muttered. Up close, I could see the dark smudgy makeup smeared under her eyes, and the safety pins in her lower lip flashed as she spoke. Today she was dressed in her standard uniform of a military surplus jacket, black T-shirt, a raggedy looking plaid skirt, torn stockings, and black Chucks. In addition to the safety pins, she also wore a variety of earrings in the outer shell of her ear, all the way from the bottom of the lobe up to where her ear touched her scalp. One of those earrings was a small silver hoop that matched the three in my left ear in virtually the same position — we got them at the same time. We’d been friends since freshman year — back when her name was April, her hair was blond, and she was the better student — so she knew the score with Brewster even if she didn’t know why.

I kept my gaze pointed down at my backpack while I pulled out the Brit lit textbook and my folder. We’d learned, the hard way, that Mrs. Pederson wasn’t as likely to catch you talking in class if she didn’t see you looking at each other. “Same old,” I said.

That wasn’t exactly true. Grandpa Brewster stood about a foot and a half off my right elbow, glowering at me, and the other dead in the room were taking notice.

In every room full of humans, you have about half as many dead. Some are associated with particular people, some are associated with a particular place, and some are just wanderers. In Brit lit, there were only about seven or eight on a regular basis. Most of them stayed tucked back out of the way — they hated the sensation of being walked through — and they didn’t usually cause a ruckus. That would change, rather quickly, though, if they found out someone could hear and see them.

In class today, we had a few grandfathers and grandmothers — I could only tell because of the clothing styles: out-of-date military uniforms, June Cleaver wide-and-puffy skirts with stiletto heels, and really short and wide ties on the men wearing suits. When people die naturally — of old age or whatever — and their energy stays here, that energy usually appears in the form of how the people thought of themselves. No one ever thinks of themselves as old, so they usually revert back to their early twenties, and the clothing changes, too.

At the front of the room, you had Liesel Marks, Mrs. Pederson’s high school best friend, and Liesel’s boyfriend, Eric. I hadn’t yet managed to catch Eric’s last name. Liesel did most of the talking. I wasn’t even quite sure why Eric was still hanging around. He seemed bored most of the time. Liesel and Eric had died in a car accident sometime in the late seventies while on their way home from the prom, hence her long polka-dot dress and his blue tuxedo. The ghosts of people who’d died violently and/or unexpectedly were essentially stuck in their moment of death.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Ghost and the Goth»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Ghost and the Goth» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Ghost and the Goth» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.