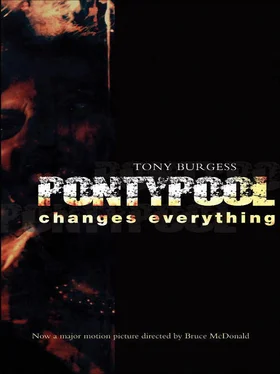

Tony Burgess

PONTYPOOL CHANGES EVERYTHING

A Novel

For my girls Camille and Rachel

with gratitude to Bruce McDonald

Rachel Jones, who makes everything possible. I love you.

Everyone at ECW and Shadow Shows. My brother Bruce McDonald.

Griffin, who laughs at Camille. And Camille, who loves boobs-stickin’-out Barbie.

Importantly, for support: Jane, Kate, Tim, Barb, Andrew, Kelly, AJ, Jesse, Krista, Susan, David, Pia, John & Edith, Pat, Bruce, Erica, Paige, Emily, Jake, and my dear mother, Audrey, gone now but remembered fiercely.

And thank you to superheroes Derek McCormack and Malcolm Ingram.

Michael Holmes for insisting we do this and, as always, for being willing to re-friend me on the way down and the way up.

This is a love song for John and Leisha’s Mother.

It wasn’t easy. I might not write another.

— Chris Knox

That night I had terrible dreams I was killing people. When I awoke it took some serious self-examination to convince myself that I was not repressing real acts of murder. So completely vivid was my sense of guilt that I felt nothing short of running through a full account of my life could provide me with the peace of mind I needed to fall back asleep. In spite of the three hours I spent combing over the details, I have, to this day, a very persistent certainty that hidden inside me is the revolting knowledge of days when I wasn’t quite myself. I now suspect that my inexplicable bouts of exhaustion are due to the massive effort of keeping those days behind me.

Down in the strange hooves of Pontypool’s tanning horses scratches one of Ontario’s thinnest winds. Cold as a needle and far too complicated to ever leave the ground, these picks of air snap at fetlocks, blackening the legs of horses. The anonymous wind gathers its speed in turns around a cannon bone and tears across the ice of a frozen pool. It feels the behaviour of more famous systems and is consumed by the complexity of its origins, breaking into mad daggers and splintering into the phantoms of horses. These horses, vacancies now, or maybe caskets, are places for the wind to rest. And when a wind rests, its heart stops and it is dead forever. The horses on the ice, built from the corpse of a breeze, skate towards each other, not breathing, but intelligent. They leap inside their crazy minds and begin to make plans.

On the shore of the pool the other horses, ageing and brown, unglue their heels from the burning snow and align their bodies with the grain of the sun, counting the minutes, eight in all, until the first warming rays fall from the star’s coat and drape across a horse’s back, raising its withers and bathing its dark crest. The horses of leather and bone and cheek and thigh climb towards an open gate in the cedar fence that surrounds the pool. On the southern post claps the fat orange mitt of a man in a bulging white coat. In his other hand he swivels a bucket, clanging a metal dish against its sides.

The horses, five of them, roll in a line through the gate and are swallowed by the south shadow of the barn before they disappear into an open door. The man closes the gate and, swinging the bucket, follows a shallow gully of mud wending through the snow to a beige truck parked at the side of the road. He walks around the vehicle kicking the heavy ice that juts out, like teeth, from its underside until it loosens and falls, intact and old, onto the soft shoulders of the road. After circling the truck twice, swiping and kicking at random, he tries the tread of his boot in the access step and climbs into the driver’s seat.

Beside him on the passenger seat is a copy of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Its leather cover is striped with road salt, the tar spine is pot-holed. The inner lining and mulling have surfaced through ruptures. Books X and XI are marked by curled strips of pink paper that would open to the story of Orpheus. On these pages are scribbles and strokes caught in the fresh yellow paths of a highlighter, and in the margins illegible markings run the full length of page after page of the book. The man drops the bucket on the passenger floor, spraying a new chain of spots across the volume, which he turns over and presses for a second into the upholstery. He pops open the glove compartment with his huge orange thumb, lifts the book in the soft potato of his mitt and drops it on a stack of crisp white flyers.

Across the top of the flyers, in lettering flown with ears and arches, are the calligraphied words: “The Pontypool Players Present King Lear. ” Beneath this: “directed by Les Reardon.” The opening performance is dated today. The man, who is in fact the same Les Reardon, claps the glove box three times until it closes. He removes his gloves and starts the truck. While he waits for it to warm up he turns on the radio.

If you’ve just tuned in we’re asking the question: Was it really our responsibility to feed the deer this winter? The problem is that the severity of the season has made food scarce. So a huge number of the deer population are not expected to survive. This huge population is a result of, is caused by, a previous government’s winter feeding program.

Les squints out through the salted windshield looking for rampant feeding programs. Or deer. He finds neither.

So what we’re asking today is this: Should we just put the whole business back in nature’s hands, or do we go on spending tax dollars to wreak ecological havoc just so a few shortsighted animal lovers can feel all warm and fuzzy? That’s the question. Hello caller. What do you make of this?

Les rotates the dome at the end of his turn signal. The switch sends a blue stream into the path of a wiper. He repeats this tiny twirl with his fingers, and he mimics the sounds made against the windshield by sucking his tongue through his lips.

I don’t think there’s any question. This is what nature wants. Let her trim the population.

OK. You don’t have a problem with preventable mass deaths?

It’s not the ones that die that are important, it’s the ones that live, the strong ones.

Survival of the fittest, eh?

You got it.

OK. Sounds good to me. Hello. Who am I speaking to?

Les rolls the window up until it seals. He breathes onto its surface, and in this opacity he draws with his finger a man in a hat. He puts a pipe in the man’s mouth, but it looks more like an oar, so he wipes the window clear with the mitt he lifts from his lap.

Peter. Listen, a living thing’s a living thing, and if we can save them we should.

But aren’t we just contributing to the problem?

No. We’re responsible for the problem, and our responsibility is to protect these herds.

Says who, Peter?

Me. I say so.

Well, if you say so Petey. Hello?

Hello. I just can’t stand to think of those poor animals starving in the cold, mothers with their little does shivering in the wind. I think it’s terrible. How much does it cost to feed them, anyway?

Well, actually, nothing, it’s always been a volunteer thing, but hey, that’s not the point. It’s not a matter of economics, it’s really a matter of what nature wants, and somehow I don’t think she spends a lot of time caring for a surplus of weakened animals at the expense of a healthy population.

Deep in the woods a female deer lies on her side as thirty baby deer slide easily from her birth canal on an immense sluice of effluence. As the moon appears above the trees its tidal effect on the afterbirth is visible. In the morning, children in full hockey gear skate across the purple and red ice, weaving around an obstacle course of tan corpses. Several of the deer stand frozen, and the children cut down all but two. They become the opposing nets of a makeshift hockey rink. A heart thawed over a small fire is used to draw the centre line and goal creases. A great deal of time is spent disembowelling the baby creatures so that their frozen feces can be used as pucks; however, having never eaten, their little bodies are as clean as packaged straws. The children settle for the mother’s hoof, which twists off easily.

Читать дальше