Dahut asked, breathlessly: "Which lived?"

I laughed: "The story does not say."

She knew what I now meant, and I watched the color creep into her cheeks and the sparks dance in her eyes. She dropped my wrist. She said:

"My father is truly pleased with you, Alan."

"I think you told me that once before, Dahut – but no gaiety followed."

She whispered: "And I seem to have heard you speaking like this before… and there was no gaiety thereafter for me… " Again she grasped my wrist:

"But I am not pleased, Alan."

"I am sorry, Dahut."

She said: "Despite his wisdom, my father is rather ingenuous. But I am not."

"Fine," I said, heartily. "Nor am I. I loath ingenuousness. But I have not as yet observed any naivete about your father."

Her grip upon my wrist tightened: "This Helen… how much does she resemble the naked but veiled lady of your quest?"

My pulse leaped: I could not help it; she felt it. She said, sweetly: "You do not know? You have had no opportunity, I take it, for… comparison."

There was mercilessness in the rippling of the little waves of her laughter: "Continue to be gay, my Alan. Perhaps, some day, I shall give you that opportunity."

She tapped her horse with her crop, and cantered off. I ceased feeling gay. Why the devil had I allowed Helen to be brought into the talk? Not choked mention of her off at the beginning? I followed close behind Dahut, but she did not look at me, nor speak. We went along for a mile or two, and came out on that haunted meadow of the crouching bushes. Here she seemed to regain her good-humor, dropped back beside me. She said:

"Divide – and rule. It is a wise saying, that. Whose is it, Alan?"

I said: "So far as I know, some old Roman's. Napoleon quoted it."

"The Romans were wise, very wise. Suppose I told my father that you had put this thought into my head?"

I said, indifferently: "Why not? Yet if it has not already occurred to him, why forearm him against yourself?"

She said, thoughtfully: "You are strangely sure of yourself today."

"If I am," I answered, "it is because there is nothing but the truth in me. So if there are any questions upon the tip of your lovely tongue whose truthful answers might offend your beautiful ears – do not ask them of me."

She bent her head, and went scudding over the meadow. We came to the breast of rock which I had scaled on our first ride. I dropped from my horse and began to climb. I reached the top, and turning, saw that she, too, had dismounted and was looking up at me, irresolutely. I waved to her, and sat down upon the rock. The fishing boat was a few hundred yards away. I threw a stone or two idly into the water, then flipped out the small bottle in which was the note to McCann. One of the men stood up, stretched, and began to pull up the anchors. I called out to him: "Any luck?"

Dahut was standing beside me. A ray of the setting sun struck the neck of the small bottle, and it glinted. She watched it for a moment, looked at the fishermen, then at me. I said: "What is that? A fish?" And threw a stone at the glint. She did not answer; stood studying the men in the boat. They rowed between us and the bottle, turned the breast of rock and passed out of sight. The bottle still glinted, rising and falling in the swell.

She half lifted her hand, and I could have sworn that a ripple shot across the water straight to the bottle, and an eddy caught it, sending it swirling toward us.

I stood up, and caught her by the shoulders, raised her face to mine and kissed her. She clung to me, quivering. I took her hands, and they were cold, and helped her down the breast of rock. Toward the bottom, I lifted her in my arms and carried her. I set her on her feet beside her horse. Her long fingers slipped around my throat, half-strangling me; she pressed her lips to mine in a kiss that left me breathless. She leaped on the bay and gave it the quirt, mercilessly. She was off over the meadow, swift as a racing shadow.

I looked after her, stupidly. I mounted the roan…

I hesitated, wondering whether to ascend the breast again to see if McCann's men had come back and retrieved the bottle. I decided I'd better not risk it, and rode after Dahut.

She kept far ahead of me, never looking back. At the door of the old house she flung herself from the back of the bay, gave it a little slap, and went quickly in. The bay trotted over to the stables. I turned across the field and rode into the grove of oaks. I remembered it so well that I knew precisely when I would reach its edge and face the monoliths.

I reached the edge, and there were the standing stones, a good two hundred of them lifting up from a ten-acre plain and hidden from the sea by a pine-thatched granite ridge. They were not gray as they had been under fog. They were stained red by the setting sun. In their center squatted the Cairn, sullen, enigmatic, and evil.

The roan would not pass the threshold of the grove. He raised his head and sniffed at the wind and whinnied; he began to shiver and to sweat, and the whinny grew shrill with fear. He swerved and swung back into the oaks. I gave him his head.

Dahut sat at the head of the table. Her father had gone somewhere in the yacht and might not return that night, she had said… I wondered, but not aloud, if he were collecting more paupers for the sacrifices.

He had not been there when I had come in from the ride. Nor, until I had sat down at the table, had I seen Dahut. I had gone up to my room and bathed and dressed leisurely. I had set my ear to the tapestry and had searched again for the hidden spring; and had heard and found nothing. A kneeling servant had announced that dinner was ready. It interested me that he did not address me as his Lord of Carnac.

Dahut wore a black dress, for the first time since I had met her. There wasn't much of it, but what there was showed her off beautifully. She looked tired; not wilty nor droopy, but in some odd fashion like a sea flower that was at its best at high tide and was now marking time through the low. I felt a certain pity for her. She raised her eyes to mine, and they were weary. She said:

"Alan, do you mind – I'd rather talk commonplaces tonight."

Inwardly, I smiled at that. The situation was somewhat more than piquant. There was so little we could talk about other than commonplaces that wasn't loaded with high explosive. I approved of the suggestion, feeling in no mood for explosions. Nevertheless, there was something wrong with the Demoiselle or she would never have made it. Was she afraid I might bring up that matter of the sacrificial bowl, perhaps – or was it that my talk with de Keradel had upset her. Certainly, she had not liked it.

"Commonplaces it is," I said. "If brains were sparks, mine tonight wouldn't even light a match. Discussion of the weather is about the limit of my intelligence."

She laughed: "Well, what do you think of the weather, Alan?"

I said: "It ought to be abolished by Constitutional amendment."

"And what makes the weather?"

"Just now," I answered, "you do – for me."

She looked at me, somberly: "I wish that were true – but take care, Alan."

"My mistake, Dahut," I said. "Back to the commonplace."

She sighed, then smiled – and it was hard to think of her as the Dahut I had known, or thought I had known, in her towers of Ys and New York… or with the golden sickle red in her hand…

We stuck to commonplaces, although now and then perilous pits gaped. The perfect servants served us with a perfect dinner. De Keradel, whether scientist or sorcerer, did himself well with his wines. But the Demoiselle ate little and drank hardly at all, and steadily her languor grew. I pushed aside the coffee, and said:

"The tide must be on the ebb, Dahut."

She straightened, and asked, sharply:

Читать дальше

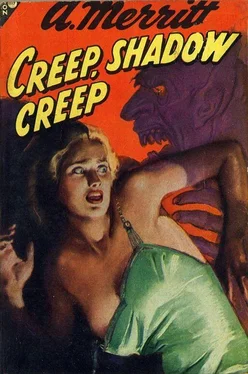

![Абрахам Меррит - Лунный бассейн [Лунная заводь]](/books/20623/abraham-merrit-lunnyj-bassejn-lunnaya-zavod-thumb.webp)