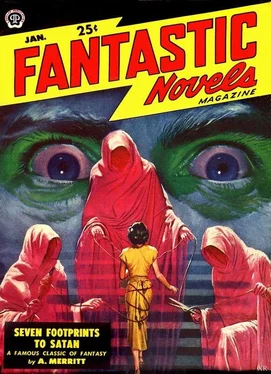

Абрахам Меррит - Seven Footprints To Satan

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Абрахам Меррит - Seven Footprints To Satan» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1927, Жанр: Ужасы и Мистика, sf_mystic, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Seven Footprints To Satan

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:1927

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Seven Footprints To Satan: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Seven Footprints To Satan»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Seven Footprints To Satan — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Seven Footprints To Satan», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"A journey," he said blandly, "never devoid of interest. But a year soon passes, and then you shall have your chance again."

"To fall, you mean?" I laughed.

"You gamble against Satan," he reminded me, then shook his head. "No, you are wrong. My plans for you require your presence on earth. I commend, however, your prudence in climbing. And I admit you- surprised me."

"I have then," I arose and bowed, "begun my bondage with a most notable achievement."

"May we both find your year a profitable one," he said. "And now, James Kirkham- I claim my first service from you!"

I seated myself, waiting, with a little heightening of the pulse, for him to go on.

"The Yunnan jades," he said. "It is true that I arranged matters so that you might retain them, if you were clever enough. It is also true that it would have amused me to have possessed the plaques. I was forced to choose between two interests. Obviously whichever way the cards fell I was bound to experience a half-disappointment."

"In other words, you observed, sir," I remarked, solemnly, "that even you cannot have your cake and eat it, too."

"Exactly," he said. "Another blunder of a bunglingly devised world. The museum has the jades; well, they shall keep them. But they must pay me for my half-disappointment. I have decided to accept something else that the museum owns which has long interested me. You shall- persuade- them to let me have it, James Kirkham."

He raised his glass to me, ceremoniously, and drank; I followed suit, with no illusion as to the word he had used.

"What is it," I asked, "and what is to be my method of- persuasion?"

"The task," he said, "will not be a difficult one. It is, in truth, in the nature of the initial deed all knights of old were compelled to perform before they could receive the accolade. I follow the custom."

"I bow to the rules, sir," I told him.

"Many centuries ago," he continued, "a Pharaoh summoned his greatest goldsmith, the Benvenuto Cellini of that day, and commanded him to make a necklace for his daughter… Whether it was for her birthday or her bridal, none knows. The goldsmith wrought it of finest gold and carnelian and lapis lazuli and that green feldspar called aquamarine. At one side of the golden cartouche that bore in hieroglyphs the Pharaoh's name, he set a falcon crowned with the sun's disk- Horus the son of Osiris, God, in a fashion, of Love, and guardian of happiness. On the other the winged serpent, the uraeus, bearing the looped cross, the crux ansata, the symbol of life. Below it he made a squatting god grasping sheaves of years and set upon his elbow the tadpole symbol of eternity. Thus did the Pharaoh by amulets and symbols invoke an eternity of love and life for his daughter.

"Alas for love and human hope and faith! The princess died, and the Pharaoh died and in time Horus and Osiris and all the gods of ancient Egypt died.

"But the beauty which that forgotten Cellini wrought in that necklace did not die. It could not. It was deathless. It lay for centuries with the mummy of that princess in her hidden coffin of stone. It has outlived her gods. It will outlive the gods of today and the gods of a thousand tomorrows. Undimmed, its beauty shines from it as it did three thousand years ago when the withered breast on which it was found throbbed with life and sobbed with love and had, it may be, its fleeting shadow of that same beauty which in the necklace is immortal."

"The necklace of Senusert the Second!" I exclaimed. "I know that lovely thing, Satan."

"I must have that necklace, James Kirkham!"

I looked at him, disconcerted. If this was what he thought an easy service, what would he consider a difficult one?

"It seems to me, Satan," I hazarded, "that you could hardly have picked an object less likely to be yielded up by any- persuasion. It is guarded day and night. It lies in a cabinet in the center of a comparatively small room, in fact, and designedly, in the most conspicuous part of that room – constantly under observation- "

"I must have it," he silenced me. "You shall get it for me. I answer now your second question. How? By obeying to the minute, to the second, without deviation, the instructions I am about to give you. Take your pencil, put down these o'clocks, fix them unalterably in your memory."

He waited until I had obeyed the first part of his command.

"You will leave here," he said, "at 10:30 tomorrow morning. Your journey will be so timed that you may drop out of the car and enter the museum at precisely one o'clock. You will be wearing a certain suit which your valet will give you. He will also pick out your overcoat, hat and other articles of dress. You must, as is the rule, check your coat at the cloak room.

"From there you must go straight to the Yunnan jades, the ostensible object of your visit. You may talk to whom you please, the more the better, in fact. But you must so manage that at precisely 1:45 you enter alone the north corridor of the Egyptian wing. You will interest yourself in its collections until 2:05, when you will enter, upon the minute, the room of the necklace. It has a guard for each of its two entrances. Do they know you?"

"I'm not sure," I answered. "Probably so. At any rate, they know of me."

"You will find an excuse to introduce yourself to one of the guards in the north corridor," he continued, "provided he does not know you by sight. You will do the same with one of the guards in the necklace room. You will then go to one of the four corners of that room, it does not matter which, and become absorbed in whatever is in the case before you. Your object will be to keep as far from you as possible either of the two attendants who, conceivably, might think it his duty to remain close to such," he raised his goblet to me, "a distinguished visitor.

"And, James Kirkham, at precisely 2:15 you will walk to the cabinet containing the necklace, open it with an instrument which will be provided for you, take out the necklace, drop it into the ingenious pocket which you will find in the inside left of your coat, close the case noiselessly and walk out."

I looked at him, incredulously.

"Did you say- walk out?" I asked.

"Walk out," he repeated.

"Carrying with me, I suppose," I suggested satirically, "the two guards."

"You will pay no attention to the guards," he said.

"No?" I questioned. "But they will certainly be paying attention to me, Satan!"

"Do not interrupt me again," he ordered, sternly enough. "You will do exactly as I am telling you. You will pay no attention to the guards. You will pay no attention to anything that may be happening around you. Remember, James Kirkham, this is vital. You will have but one thought- to open the case at exactly 2:15 and walk out of that room with Senusert's necklace in your possession. You will see nothing, hear nothing, do nothing but that. It will take you two minutes to reach the cloak room. You will go from there straight to the outer doors. As you pass through them you will step to the right, bend down and tie a shoe. You will then walk down the steps to the street, still giving no attention to whatever may be occurring around you. You will see at the curb a blue limousine whose chauffeur will be polishing the right-hand headlight.

"You will enter that car and give the person you find inside it the necklace. The time should then be 2:20. It must not be later. You will drive with that person for one hour. At 3:20 you will find the car close to the obelisk behind the museum. You will descend from it there, walk to the Avenue, take a taxi and return to the Discoverers' Club."

"The Discoverers' Club, you said?" I honestly thought in my astonishment that it had been a slip of his tongue.

"I repeat- the Discoverers' Club," he answered. "You will upon arriving there go straight to the desk and tell the clerk on duty that you have work to do that demands absolute concentration. You will instruct him not to disturb you with either telephone calls or visitors. You will say to him that it is more than likely reporters from the newspapers will try to get in touch with you. He will tell them that you left word that you would receive them at eight o'clock. You will impress it upon him that the work which you have to do is most important and that you must not be disturbed. You will further instruct him to send up to your room at seven o'clock all the late editions and extra editions of the afternoon newspapers."

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Seven Footprints To Satan»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Seven Footprints To Satan» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Seven Footprints To Satan» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Абрахам Меррит - Лунный бассейн [Лунная заводь]](/books/20623/abraham-merrit-lunnyj-bassejn-lunnaya-zavod-thumb.webp)